L.A. County sets high goal to get all veterans off the street by 2016

- Share via

Traipsing through skid row, trailing media cameras and advance staff, U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro stopped to talk to a homeless woman with a white blanket draped over her head.

“What a privilege and honor,” said Jennifer Campbell, 64, who would sleep on aflowered quilt on the sidewalk Thursday night. “I’m writing a book called ‘I lost my mind on skid row but I found it on skid row.’”

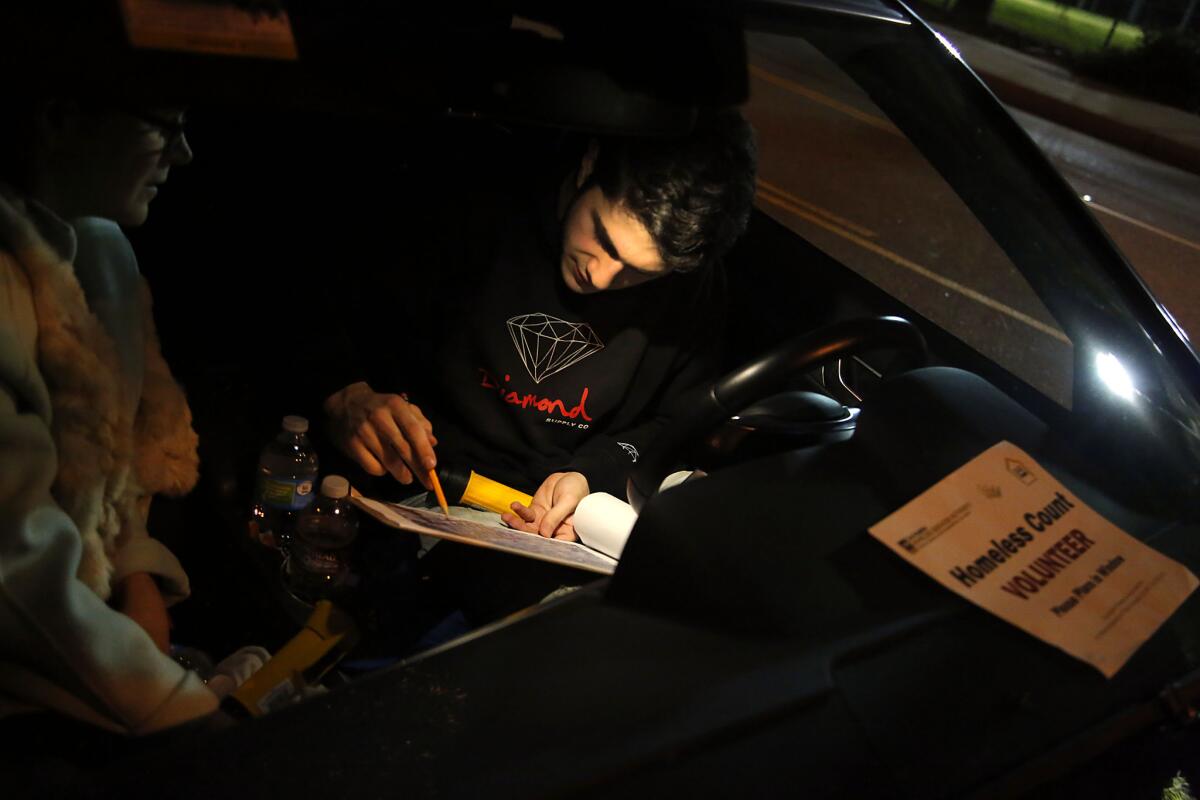

Castro’s visit was part of what felt like Super Bowl week for Los Angeles’ long campaign to end homelessness. Castro and another Cabinet member, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Secretary Robert A. McDonald, joined thousands of volunteers for Los Angeles County’s biennial homeless tally, which wrapped up late Thursday.

The day before, McDonald had announced a legal settlement that officials said would transform the VA’s sprawling West Los Angeles campus into a permanent housing center for homeless veterans. Earlier Thursday, local business and political leaders said Los Angeles’ homelessness fight had turned the corner. They pledged to get every veteran off the streets by the end of the year.

“Four years ago, federal authorities told us: L.A. is dysfunctional, we’re not going to invest in you,” said Elise Buik, president of the United Way of Greater Los Angeles, which joined with the Chamber of Commerce to start a private-public homelessness collaboration called Home for Good.

But “it’s a new day,” she said.

Speaking at a former skid row flophouse converted to homeless housing, the leaders highlighted new federal resources coming Los Angeles’ way for homeless people.

Mayor Eric Garcetti said that $13 million awarded to the city last week by the Housing and Urban Development Department — along with housing vouchers — will be used to create 1,300 homes with counseling, drug treatment and other services attached. McDonald also pledged to provide $50 million and 400 workers to locate veterans in riverbed and canyon encampments across the county and find them housing.

The leaders touted their move toward tactics such as “housing first,” which requires finding homes for people instead of insisting that they first treat their mental illnesses or addictions, and coordinated entry, a computerized system that matches the most vulnerable people with appropriate housing and services, putting an end to long waiting lists.

When Castro arrived Thursday night, the new strategies had yet to budge the tents and makeshift shelters lining the sidewalks of skid row. The former mayor of San Antonio said Los Angeles’ skid row was probably the nation’s most extensive homeless community, noting that his city had a much smaller one.

“Where are they from, the army?” one man sitting on the curb in front of his tent called out as Castro’s entourage, slowly tailed by police cars, strode by.

“It’s the count,” a curbside woman told her friend.

“Oh, the count. There’s lots of us,” the friend called out.

Castro stopped to thank a veteran for his service. John Hulett said he drank after leaving the armed services in 2004, lost his job and landed in the streets. Now, he told Castro, he’s in a VA residential program at the Weingart Center, a skid row homeless center, and getting back on his feet.

“We reduced veteran homelessness 33%,” Castro told him, adding that the goal was to eliminate it altogether by December. “It’s a stretch goal.”

Several homeless people were surprised but not overly impressed to find a Cabinet secretary in their midst.

“That’s cool,” said a one-eyed man, striking a pose like an action star. “Can you put me in a movie?”

Campbell expressed her appreciation for the Section 8 housing vouchers that Castro’s agency doles out, which enabled her to live in a skid row hotel for three years before she ended up homeless again several months ago.

Skid row is not all bad, she told Castro. “I prefer living in skid row,” said Campbell, who said she once taught special education in Philadelphia. “I’ve lived in Beverly Hills. It’s much more decent here.

“If people are just given a little push, they’ll get up.”

Castro said he was moved by the personal stories he heard. “The woman writing a book … she doesn’t feel unsafe in the area. It’s a testament to the way people adapt,” he said. “But I want to make sure they get into services and have an opportunity for a better life.”

[email protected]

Twitter: @geholland

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.