From the Archives: Secret clique in L.A. County sheriff’s gang unit probed

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on April 20, 2012.

Los Angeles County sheriff’s detectives have launched a probe into what appears to be a secret deputy clique within the department’s elite gang unit, an investigation triggered by the discovery of a document suggesting the group embraces shootings as a badge of honor.

The document described a code of conduct for the Jump Out Boys, a clique of hard-charging, aggressive deputies who gain more respect after being involved in a shooting, according to sources with knowledge of the investigation. The pamphlet is relatively short, sources said, and explains that deputies earn admission into the group through the endorsement of members.

The sources stressed that the internal affairs investigation is still in its early stages and that little is known about the Jump Out Boys’ behavior or its membership.

Still, sheriff’s officials are concerned that the group represents another unsanctioned clique within the department’s ranks, a problem the department has been grappling with for decades.

Last year, the department fired a group of deputies who all worked on the third, or “3000,” floor of Men’s Central Jail, after the group fought two fellow deputies at an employee Christmas party and allegedly punched a female deputy in the face. Sheriff’s officials later said the men had formed an aggressive “3000” clique that used gang-like three-finger hand signs. A former top jail commander told The Times that jailers would “earn their ink” by breaking inmates’ bones.

Other cliques — with names like Grim Reapers, Little Devils, Regulators and Vikings — have been accused of breeding a gang-like mentality in which deputies falsify police reports, perjure themselves and cover up misconduct.

The investigation into the Jump Out Boys is focused on the sheriff’s Gang Enforcement Team. The unit is divided into two platoons of relatively autonomous deputies whose job it is to target neighborhoods where gang violence and intimidation area concern.

The sources, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the case was ongoing, described parts of the memo to The Times. The pamphlet extols hard work and other positive virtues, but there is concern that some of the language conflicts with department expectations.

Most notably, sources said, was a positive depiction of officer-involved shootings. A distinction is made, sources said, between cops who have and cops who have not been involved in shootings.

But the attitude is troubling because officer-involved shootings, even those that are within policy, are expected by the department to be treated as events of last resort. Sheriff’s officials have warned against forming rogue subgroups because they threaten to stress allegiance to the clique and subvert loyalty to the department and its policies.

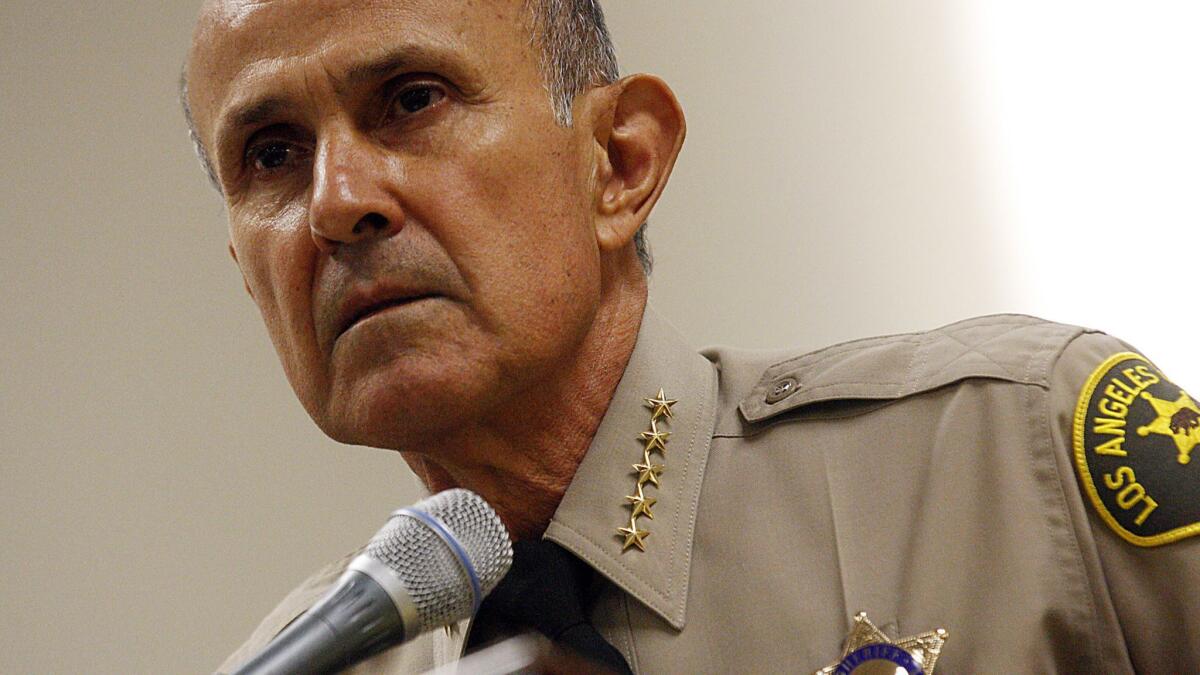

Sheriff Lee Baca’s spokesman said the department is taking the issue seriously, and detectives are gathering evidence and conducting interviews.

“We’re going to be looking at this right now, but it really could be a fantasy, something that’s not true but right now we’re going to find out exactly what is and what isn’t and that will determine what our next step is,” spokesman Steve Whitmore said.

Whitmore declined to discuss details of the investigation or the contents of the document. Asked about the language that portrays shootings in a positive light, he said, “The last thing anybody wants to do in law enforcement is shoot a weapon.”

Whitmore said Baca understands that deputies might bond and form social groups with close co-workers but prohibits cliques when “it does not embrace the integrity to do what is right.”

Historically, within the Sheriff’s Department, the groups have been tied to patrol stations. In one instance, a federal judge called one of those groups, the Lynwood Vikings, a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” that had engaged in racially motivated hostility. As part of a 1996 settlement, the county agreed to retrain deputies to prevent such conduct and pay $7.5 million to compensate victims of alleged abuses.

Affiliation with such groups reaches the highest levels of the department, all the way up to Baca’s second-in-command, Paul Tanaka, who the sheriff acknowledged in an interview last year still had his Vikings tattoo.

In February, The Times reported allegations that a supervisor inside the sheriff’s Compton station aimed a gun at the head of a fellow sergeant, who alleged the threat was part of a vendetta motivated by ties to a secret deputy clique.

Maria Haberfeld, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York who specializes in police ethics and training, said police subcultures can provide officers with much needed support in a dangerous job. But she said that closeness can become problematic.

“Solidarity is one of the main things of police subculture,” she said, “so the closer the group, the higher the possibility that various cases of misconduct will be covered up.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.