In a paved, urban world, nature makes a rare appearance — delighting kids near MacArthur Park

- Share via

Nathan Hobbs couldn’t believe his eyes.

He rubbed them with his fists, he blinked, then he looked once more.

There it was, just a few days after Thanksgiving, perched on the branch of a coral tree outside Ms. Gil’s classroom.

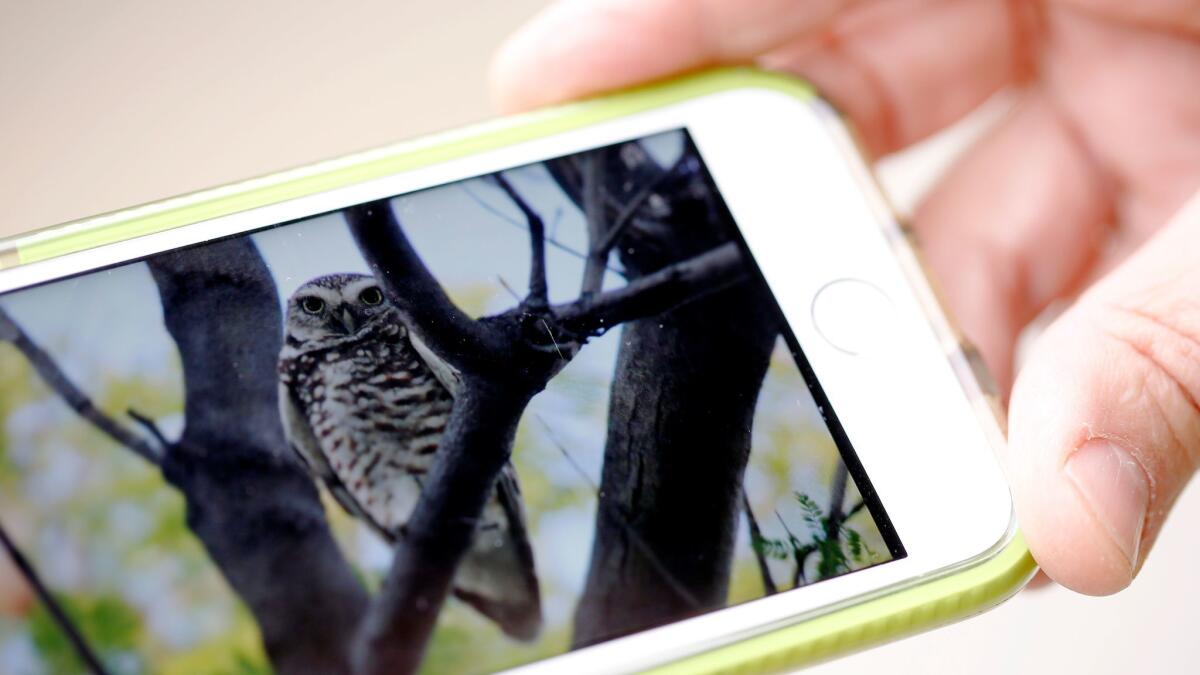

Some sort of owl with long legs, white brows and bright, yellow eyes.

Nathan, 9, had no idea how the bird found its way to the courtyard of his school, Esperanza Elementary, near MacArthur Park in the middle of the city.

“This is a big deal,” he thought.

Nathan told a teacher, who then told Brad Rumble, the school’s principal and a man who takes bird matters very seriously.

Rumble pulled a few students out of class to observe the visitor, identified as a burrowing owl. In a neighborhood of asphalt, street vendors and crowded apartment buildings, this was their closest encounter yet with nature.

And chances were, the bird — of a species that usually lives in deserts and grasslands — wouldn’t stay long.

Decades ago, before buildings and cars covered Los Angeles, burrowing owls were a common sight, said Kimball Garrett, an ornithologist who manages bird collections at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Now, sightings are rare. The last one spotted near downtown Los Angeles was six years ago, near the museum.

“It’s not unprecedented to see one every once in a while,” Garrett said. “But it’s still pretty special to have one hanging around a schoolyard.”

He suspects the owl, which is active day and night, has been getting by in the city on moths and beetles it catches around the school’s lampposts.

Rumble thinks he knows what attracted the bird. In mid-November, he teamed up with the Los Angeles Audubon Society to transform more than 4,000 square feet of asphalt on campus into a native habitat.

High school students helped Esperanza families lay down a bark path and plant California golden poppies, an oak tree and a sycamore.

“It’s not natural around here for kids to come down from their apartments and walk down to the creek and play,” the principal said. “But if the neighborhood is lacking, at least the school campus can serve as a living laboratory.”

He created something similar once before — with remarkable results.

A few years ago, at Leo Politi Elementary in Pico-Union, he had 5,000 square feet of concrete ripped out and replaced with native flora.

The plants attracted insects, which attracted birds, fascinating students. They learned so much, their test scores in science rose sixfold, “from the basement to the penthouse,” Rumble told The Times in 2012.

At Esperanza, where Rumble has been for three years, he’s kept birds a top priority. Parrot statues populate a counter in his office, which features carved toucans on the desk, painted eagles on the file cabinets and framed ducks on the wall.

He goes on bird-sighting hikes, keeps binoculars in his trunk and has numbers for the town’s top bird experts on his cellphone.

At school, his enthusiasm is infectious. He printed 900 photos of the visiting owl, one for each student to take home for Christmas.

Since the owl showed up on campus, peculiar things have happened: Students have skipped recess to stay in the library, poring over books about falcons, swallows and hummingbirds. Some have pulled their parents out of their cars after school to hunt down the owl’s droppings. Teachers watched in shock one day when two crows tried to attack the school’s honored guest.

Rumble encourages students to use an observation board he set up outside the main office to document each owl sighting. There have been more than a dozen so far — on drainpipes, rooftops, PA speakers, even a library rolling cart. For more than a week, the owl frequented a jacaranda tree located next to the lunch tables, amusing the 200 kids who munched on pizza and sandwiches below.

The bird has caused such a stir, the student council is considering changing the school’s mascot from a dragon to an owl.

On a recent morning, teacher Elizabeth Williams talked with her third-graders about the bird’s diet, markings and nesting habits. She introduced new vocabulary: perch, burrowing, conservation, habitat.

“It likes to burrow in nests underground,” said Emily Guzman.

“It bobs its head up and down to protect itself,” said Yonathan Trujillo.

“It makes sounds like a snake,” said another student.

Some students are getting quite savvy about birds. They see them soar overhead, dark specks in a blue sky, and know them by name: a yellow-rumped warbler, a red-tailed hawk, a common raven.

“The other day, there was a mourning dove in the habitat,” said Emmanuel Alonzo, 9. “It was hiding in the rocks, but I knew it was there.”

Nathan, the owl’s discoverer, is hopeful that the bird will make Esperanza its permanent home.

“Maybe it will have babies,” he said. “Maybe we will have a school full of burrowing-owl babies.”

Many of the school’s families come from Guatemala, where owls are considered signs of good luck and abundance. Like them, Rumble thinks the owl’s presence is no coincidence.

The timing is good. This immigrant neighborhood has been jittery since the presidential election.

A few weeks ago, Jose Arellano, 10, lost his mother to cancer. Then his father tried to help a neighbor who was locked out of her apartment, and he ended up breaking both of his legs.

As Jose left campus with his dad in a wheelchair on a recent afternoon, Rumble stopped him.

When he asked Jose what he thought of the bird, the boy’s eyes glowed and he smiled.

“It’s made me very happy,” Jose said.

Twitter: @LATBermudez

ALSO

Riders stuck 130 feet in the air on malfunctioning ride at Knott’s Berry Farm

The secretive world of illegal warehouse concerts gets little scrutiny from L.A. officials

L.A. councilman proposes banning adults unaccompanied by a child from playgrounds

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.