Column: She got death sentence for murdering her kids. Her ex-husband is angry at Newsom’s reprieve

- Share via

The salty marine air was coming off the bay as we crossed the grounds of San Quentin State Prison just before midnight and entered the building that houses the death chamber.

It was December 2005, and I was about to witness an execution. Stanley “Tookie” Williams, one of the early leaders of L.A.’s Crips gang, was to be put to death by lethal injection.

I was one of three dozen people who assembled in a small amphitheater. Some knew Williams; others knew the four people Williams had shotgunned to death. I was there because members of the media are invited to bear witness.

Curtains separated us from the chamber, as if we were awaiting a show. And then they were pulled open to reveal the man who was about to die.

The attendants had trouble pricking a vein for the lethal injection. They kept trying and Williams grew exasperated. Finally, success. He turned to look at each of us, through the window, before closing his eyes.

I left the prison thinking I was fine, but for weeks after, I’d find myself restless and disturbed by what I had seen. I had no soft spot for Williams. But the sight of a man being executed by the state in a choreographed ceremony, because we deem murder a heinous crime, still haunts me.

That was the first thing I thought about when I began reading an email I received on the day California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered a moratorium on the death penalty,

“I am a Los Angeles physician whose three children were murdered by their mother on November 22, 1999,” wrote Dr. Xavier Caro, who asked if I cared to hear why he so objected to what Newsom had done.

The headline-grabbing case was a shocker in many ways. Caro was a prominent rheumatologist; his wife, Socorro, was a well-known mom in the family’s Ventura County community. But the couple’s marriage was falling apart, and Caro returned home from his office in the San Fernando Valley late one evening to discover a horrific scene.

As he testified in court, Caro found three of the couple’s sons — Joey, 11; Michael, 8; and Christopher, 5 — dead from gunshot wounds. His wife lay bleeding on the floor, still alive after an apparent suicide attempt. Their fourth child, a toddler, was unharmed.

At trial, the defense argued that Socorro Caro was not the killer but a victim of a sinister plot by her husband to frame her for crimes he had committed. The jury didn’t buy it, nor did it buy a defense of not guilty by reason of insanity. Socorro Caro, who recovered from her wounds but claimed she could not remember the events of that night, was convicted of murdering her children with a Smith & Wesson revolver and sentenced to death. She has been in prison ever since.

In his email to me, Caro said he has been recovering gradually in the two decades since the murders and has “achieved a modicum of peace.” But he was shaken by Newsom’s announcement, and disappointed that his ex-wife might not ever have to “take responsibility” for what she did by having her sentence carried out.

To some, Newsom’s decision was heroic, even though only the courts or a statewide ballot initiative could permanently end the death penalty in California. To others, like Caro, the governor’s action subverted the will of voters, who have repeatedly rejected measures to end public executions.

Despite the impact of my visit to San Quentin in 2005, I honestly don’t know how I’d feel about the death penalty if I were in the shoes of someone like Dr. Caro.

I know I’d be filled with rage, anger, hatred. I don’t know what I would do with those emotions, or what I’d want someone else to do.

So I decided to hear what Caro had to say.

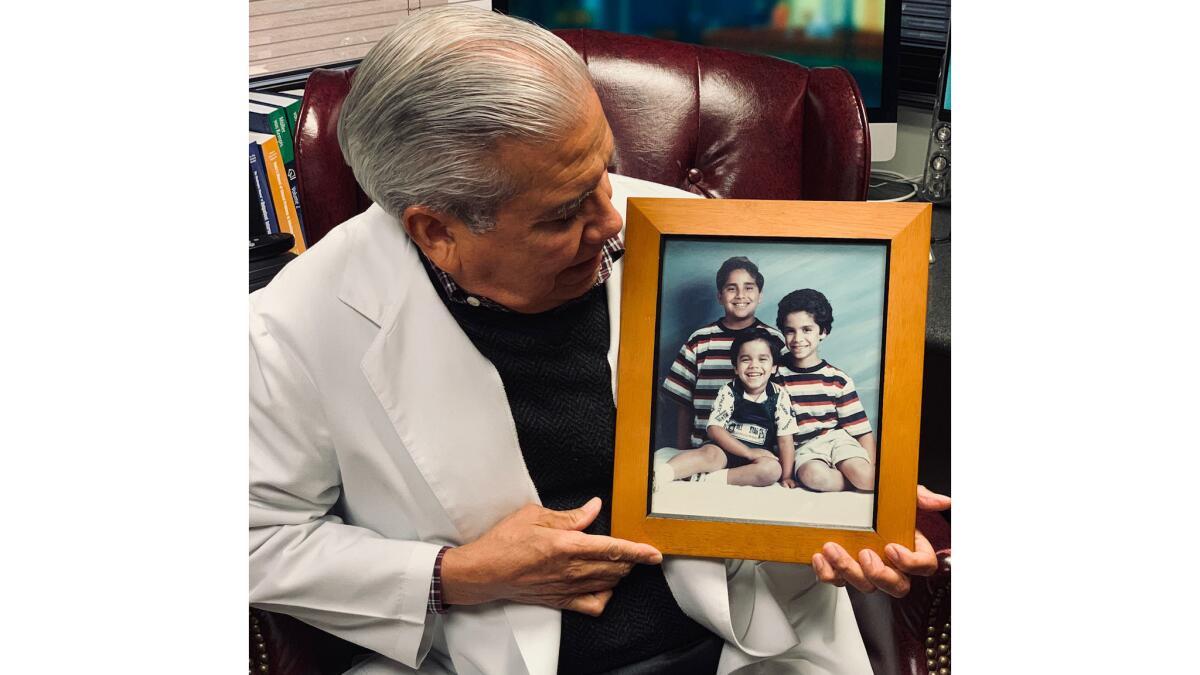

His Northridge office is filled with photos of his family, including the sons he lost. Caro smiles when he mentions that the one son who was not killed, now 20, is an aspiring artist. The doctor got married again but is going through a divorce at the moment.

READ MORE: These are the 737 inmates on California’s death row »

Caro said he doesn’t recall having strong feelings about the death penalty before the murder of his children, but called himself “a fairly conservative guy” before and after the crime.

“I believe in fairly strict adherence to the law, and I have great respect for the law. That’s the way I was raised, and it’s the way I raised my children,” he said.

Caro is a Catholic, and I pointed out that the church takes a different view of the death penalty than he does. “The dignity of the person is not lost even if he has committed the worst of crimes,” Pope Francis has said. “No one can take his life and deprive him of the opportunity to embrace again the community he hurt and made suffer.”

Caro said he respects the church’s position. “But they would have to recognize that I am a sentient being, able to come to my own opinion.”

Caro, whose family roots are in Mexico, is well aware of all the arguments against the death penalty, and he doesn’t outright dismiss any of them.

He knows that people of color dominate death rows in the United States, which might suggest racism, societal divides and a tilted criminal justice system.

He acknowledges the possibility that sometimes innocent people are executed.

And he has seen firsthand that the death penalty legal process is slow and expensive.

None of that clouds Caro’s recollection of what happened on Nov. 22, 1999, and what kind of punishment it deserves. He told me he can’t say the death penalty is appropriately applied in every case, but he believes it was in the killing of his children.

I told Caro about my trip to San Quentin, and how it solidified my own opposition to the death penalty. But I told him I respected his view.

For me, life in prison without the chance of parole seems in some ways a harsher sentence than the early escape that death brings. Caro doesn’t see it that way.

He told me that after the crime but before his ex-wife was convicted, he wanted to see for himself what her life might look like. A defense attorney arranged for him to visit the women’s prison in Chowchilla, where she was ultimately sent.

“I didn’t ask, nor did they offer, to show me death row. But I got to see the general population area … and to be honest with you, I saw it as a summer camp with a fence around it,” Caro said. “From all my contemplation and upbringing and my belief system, it didn’t seem like punishment at all. I realize there would be those who disagree with me, but that’s just how I felt, and I’m not going to deny that.”

Support for the death penalty among victims and their families is not uncommon, but there are exceptions. Beth Webb, whose sister was one of eight people killed in Seal Beach in 2011 by a gunman involved in a custody dispute with his ex-wife, told me she wouldn’t judge Caro or anyone who has lost a loved one to violence. Webb opposed the death penalty before her sister’s death, and she didn’t change her view afterward.

Still, she said, there were times when she hoped her sister’s killer would die in prison, where he was sentenced to life.

“That feeling could have destroyed me, I believe, and I knew it wasn’t who I am. It took a conscious effort to stop thinking about him and to stop hating him and to think I’m better than he was at the worst moment in his life,” Webb said. Since her sister’s killing, Webb has become a board member of Death Penalty Focus, which advocates for its abolition.

Dr. Caro, on the other hand, said he sees a duty, in a society of laws, to send a clear message. Those who take a life should, in his opinion, pay with their own.

“Please, this fellow who killed 50 people in New Zealand, is there anyone who believes he should have life in prison without possibility of parole? Well, there are, I’m sure. But I’m not one of them,” Caro said. “That is a heinous crime, so far beyond the pale it’s a no-brainer.”

And yet, when I checked after our interview, New Zealand is one of the more than 100 countries that have no death penalty.

When I asked Caro why he thought his ex-wife killed their children, he paused before answering.

“This is speculative,” he said, “but my sense is that she had a borderline personality disorder.”

But is it appropriate for us to execute people who might have some form of mental illness?

“Well, my understanding of the law is that it’s not a question of whether you’re mentally ill or have a personality disorder,” Caro said. “It’s a question of whether you know right from wrong …when you’re taking another person’s life.”

That’s a complicated matter, and one — like the death penalty — people will always disagree on.

Caro said that though he disagrees with his church on the death penalty, his faith works for him in other ways.

“I look forward to seeing my children again someday,” he said.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.