What we know about California’s largest toxic cleanup: Thousands of L.A. County homes tainted with lead

By this fall, California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control plans to begin removing lead-tainted soil from 2,500 residential properties near the shuttered Exide Technologies battery recycling plant in Vernon.

The cleanup — the largest of its kind in California history — spans seven southeast Los Angeles County neighborhoods, where plant operations have threatened the health of an estimated 100,000 people.

More than two years after the possibility of federal criminal charges forced the plant to shut down, however, the state has refused to release crucial information about the contamination and cleanup requested by lawmakers, community members and reporters.

Here’s what The Times has learned through repeated questions and records requests — and what is still left unanswered.

What are the health risks?

Lead is a poison that, even in small amounts, can lower children’s IQs and cause other developmental harm.

From 1922 to 2014, regulators say, the Vernon plant’s lead-smelting operations deposited the harmful metal in the soil up to 1.7 miles away.

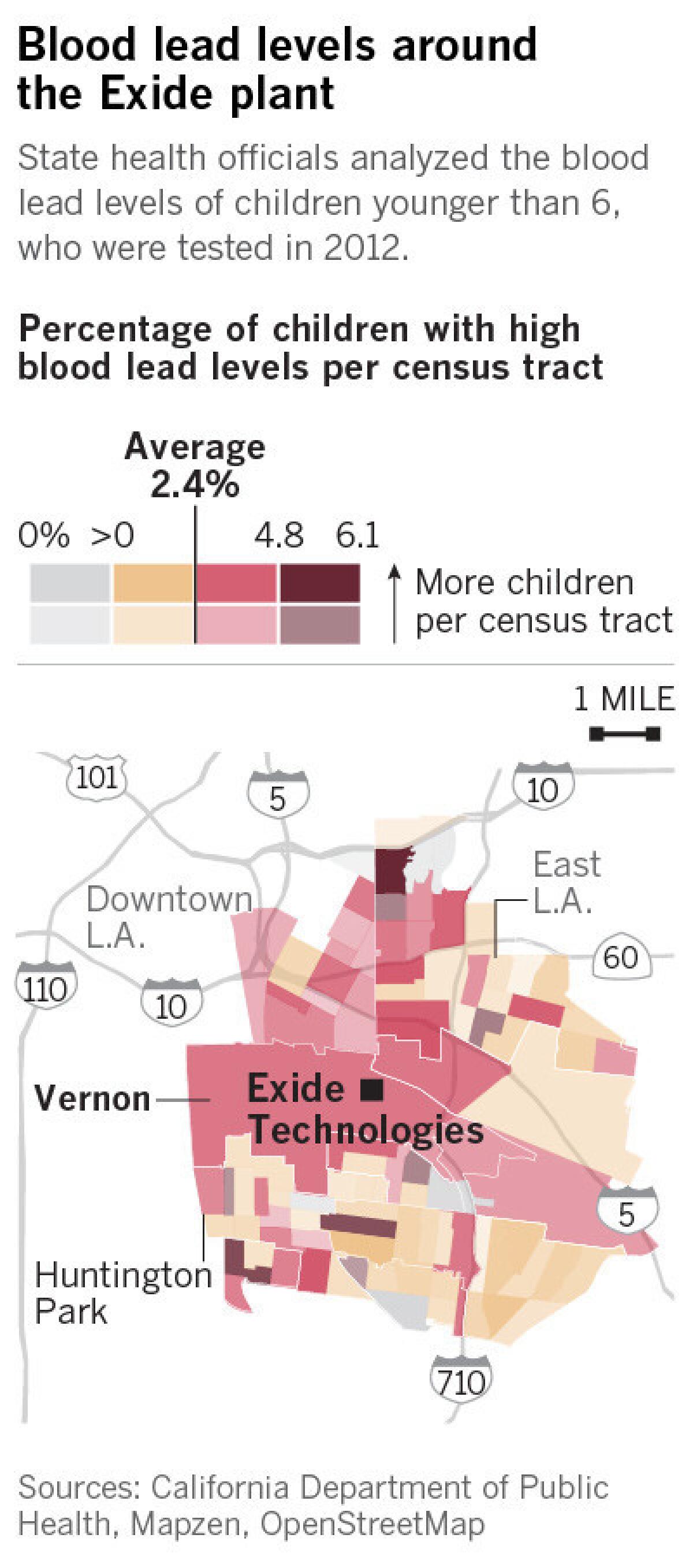

According to an analysis released last year by the state public health department, nearly 300 children younger than 6 living near Exide had high blood lead levels in 2012 — the last year the plant was in full operation. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers blood lead levels of 5 micrograms per deciliter or more to be elevated.

County health officials are administering a free blood-testing program for people living near the facility, funded with $2 million from Exide. Fewer than 0.5% of the children tested so far have had high blood lead levels, according to the county.

What neighborhoods have been affected?

Regulators say lead emissions from the Exide plant drifted across an area of more than 10,000 residential properties spanning seven communities: Bell, Boyle Heights, Commerce, East Los Angeles, Huntington Park, Maywood and Vernon. The affected neighborhoods are predominantly Latino, with about 30% of people living in poverty; the countywide poverty rate is 18%.

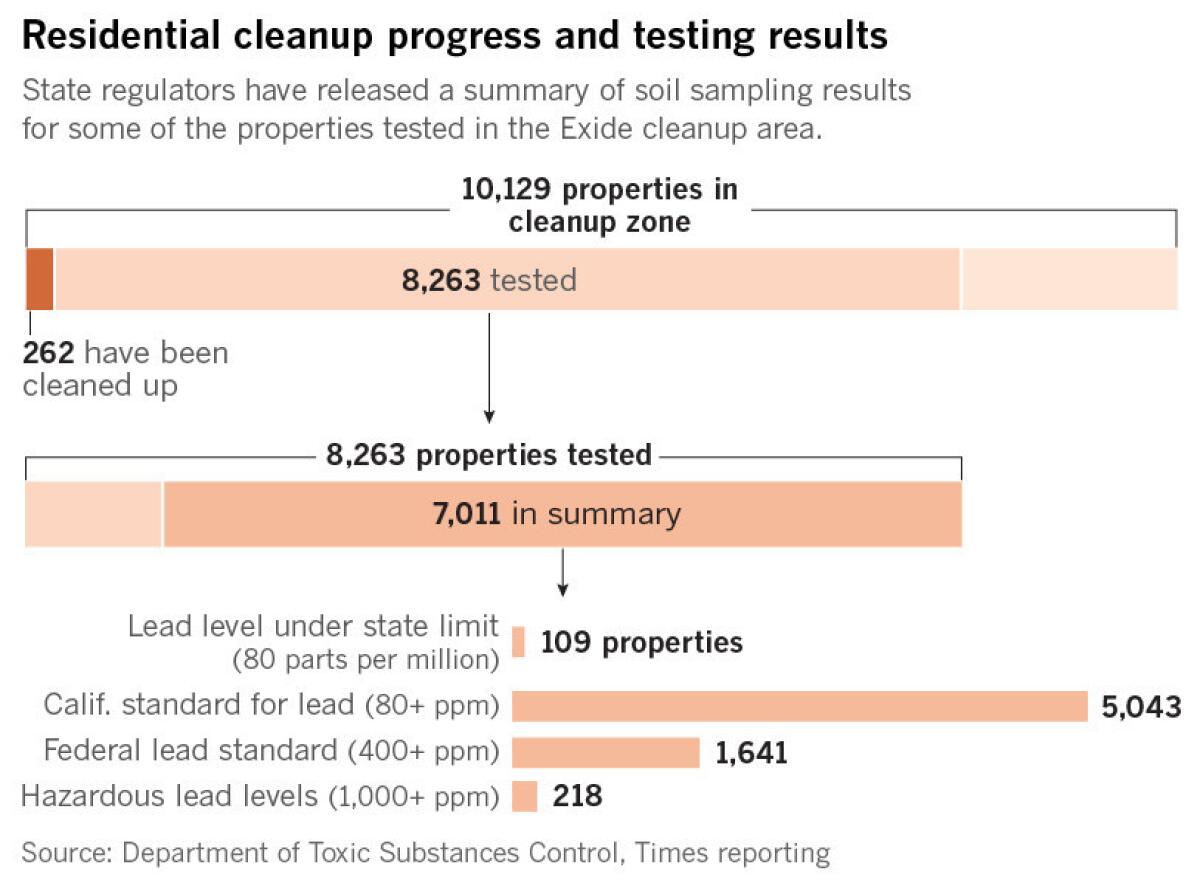

Crews so far have tested the soil of more than 8,200 properties. In its July 6 cleanup plan, the state summarized sampling results for more than 7,000 of those — and more than 98% showed lead levels exceeding 80 parts per million, California’s health standard for residential soil.

The toxic substances control department has released spreadsheets containing detailed sampling data on about 1,900 residential properties, and recently made public the addresses and parcel numbers of a few dozen child care facilities where crews sampled the soil or detected elevated lead levels. But the department has not released the precise locations of homes tested.

The Times has sought sampling results by parcel, address, map coordinates and block number, based on the public’s right to know the extent of contamination and how the government is spending public funds.

The toxic substances department argues that disclosing such information would compromise residents’ privacy, expose sensitive health information and discourage participation in soil sampling and cleanup. Though the data pertain “to soil lead levels, not personal blood lead levels,” department lawyer James Mathison said in a March letter, “there is a potential correlation to be made between identifying particular locations with high soil lead levels and correspondingly high blood lead levels” of people living there.

More than half of the households surveyed recently by county health officials reported that they have not received results from the soil testing completed in their yards. Figures released by the toxics department show that as of late July, it had yet to send results to more than 2,000 parcels — about one-quarter of those tested.

Officials said more results are being mailed to residents weekly.

Georgia-based Exide, which acquired the plant in 2000, has said its lead emissions did not extend into residential areas — and has pointed the finger at other industries, lead-based paint in older homes and past emissions from vehicles.

The company filed a lawsuit last year seeking blood lead data on people tested in L.A. County, including each person’s age, city and ZIP Code; the age of the home in which each person lived; and any causes of lead poisoning. The state is fighting the lawsuit in court, calling it an attempt by Exide to dodge financial responsibility and blame the contamination on lead paint and gasoline.

How many homes have been cleaned — and where?

Crews have removed lead from 262 residential properties since elevated levels of the poisonous metal were discovered in neighborhoods near the plant more than three years ago.

Beginning in August 2014, Exide — under state oversight — paid contractors to clean 186 tainted properties in Boyle Heights and Maywood. From November 2015 to June 2016, crews cleaned another 50 homes farther from the plant, using $7 million in taxpayer funds set aside for sampling and remediation. Cleanup work then stood at a standstill for months, with regulators arguing they could not remove lead-polluted soil from any properties amid a yearlong environmental review.

In January, the department announced an expedited cleanup program for the highest-risk properties. Crews have cleaned 26 parcels since then, according to the department.

Despite requests from The Times, state toxics officials have not released records detailing the dates and locations of completed cleanups.

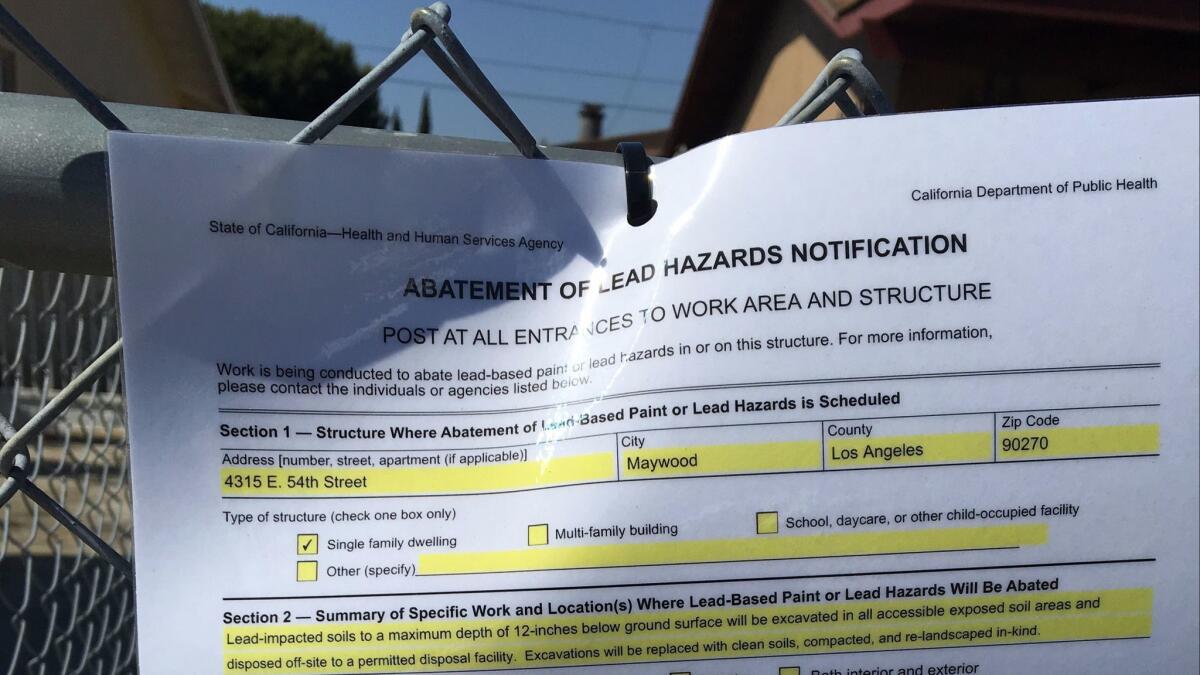

The state health department has not allowed The Times to access lead hazard notification records that are posted outside each yard before it is cleaned.

Which properties are in line to be cleaned?

Under new state guidelines, yards will be selected for cleanup if they meet certain lead thresholds. Also slated for cleanup are dozens of child care centers and a handful of schools and parks within the contamination zone.

In its cleanup plan, the state estimates that with the money available, it will be able to clean approximately 2,500 properties “with the highest levels of lead and greatest potential health risk.” Soil removal should begin after a contractor is selected this fall, officials said, and the effort will take about two years.

State Assemblyman Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles) called the plan “a step in the right direction” but complained that the years-long timeline for cleaning homes “defies all logic.”

“I know that everybody would like everything to happen faster than it does,” Barbara Lee, director of the Department of Toxic Substances Control, told reporters last month. “But if you look at these cleanups across the nation, what DTSC has been able to do in a year’s time is really extraordinary.”

How much is being spent on testing and cleanup?

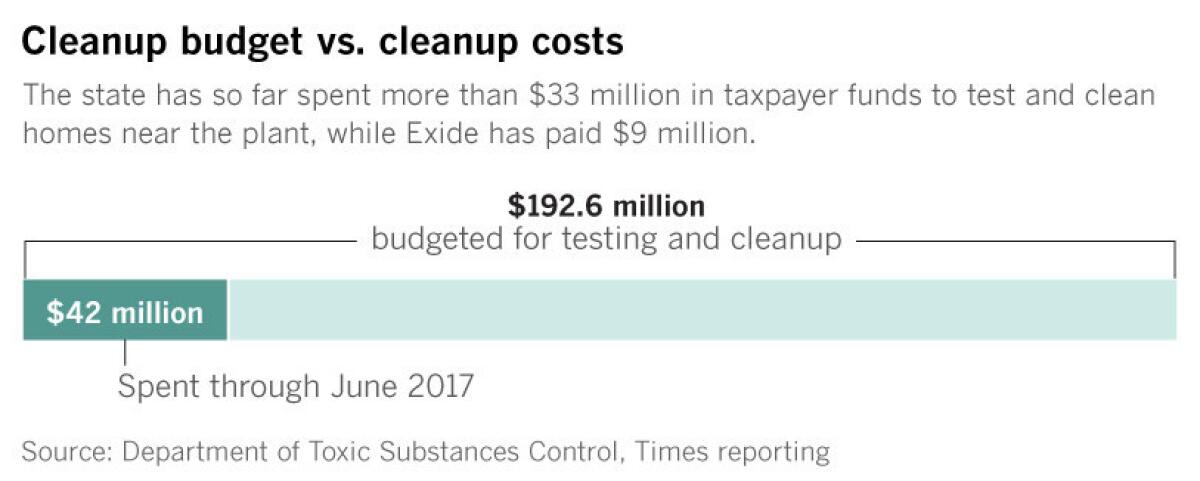

More than $192 million has been set aside for the project, most of it in April 2016, when Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation authorizing $176.6 million to test all 10,000 properties and remove lead from about 2,500 of them.

At least $42 million already has been spent. Taxpayers are footing most of the bill, at least for now.

Exide paid $9 million into a trust account during the project’s first phase of testing and cleanup and is obligated to make additional payments in the future. Through the attorney general’s office, the state has vowed to go after Exide and any other responsible parties to recoup costs, in what is likely to be a protracted legal fight.

The state toxics agency took more than 10 months to turn over records detailing its expenditures on the project. You can view them here.

Neighborhood groups and area elected officials said they have struggled to get officials to answer basic questions about the project.

“Years go by and we’re not getting the information,” said Teresa Marquez, president of Mothers of East Los Angeles. “We don’t even know what houses they’re cleaning. So it’s not transparent.”

State toxics department spokeswoman Rosanna Westmoreland said that the agency “is working hard to release as much information as possible” but that the scale and complexity of the project makes that difficult.

What happens to contaminated properties that don’t make the cut?

Though the toxics department estimates that the soil of nearly 10,000 properties may need to be cleaned, it has not committed to remediating any beyond the 2,500 covered by its cleanup plan.

For now, that leaves thousands of families whose yards are contaminated with no timeline for when to expect cleanup, if at all. According to officials, the state’s ability to clean additional homes depends on funding. Their plan is to notify residents whose homes will not make the current cut and provide them fact sheets on how to minimize their exposure to lead.

“We’re not going to tell them, ‘Your property is not going to be cleaned up or doesn’t need to be cleaned up,’ ” Mohsen Nazemi, a toxics department deputy director, told residents and community leaders at a public meeting July 20. He disputed the suggestion that the department was leaving residents behind, saying, “They’re not forgotten, they’re just not in this phase of cleanup.”

Angry community members and elected officials say the toxics department should offer some assurance that it will continue cleaning homes after 2019 using other funds — including revenue from new fees state lawmakers imposed on the sale of lead-acid batteries, the kind that were melted down at Exide.

Those fees — which Westmoreland said were among the “potential options for funding further sampling and cleanup activities” — took effect April 1 and could raise up to $26 million a year for sites contaminated by battery-recycling operations, according to state estimates.

Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens), who authored the legislation, said she expected those funds to grow over the next two years while crews clean the 2,500 properties near Exide.

“There should be enough money so there is no interruption and the work continues at a similar pace,” Garcia said. But in the meantime, she added, “I find it really irresponsible to tell the public that we don’t know if we’re going to take care of you. I have constituents that are panicked that they’re going to be left behind.”

Twitter: @tonybarboza

Twitter: @bposton

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.