The classic Crete

- Share via

A mighty wind buffeted our Olympic Airways jet, bouncing it around as we descended at Heraklion, Crete’s capital.

As I maneuvered my stick-shift rental Opel through a maze of Heraklion’s narrow one-way streets, desperately searching for the one that would lead me to Lato Hotel — which I could see but not reach — drivers squeezed past, sitting on their horns, revving their engines.

Was it an ill wind, I wondered, that had blown me here?

Heraklion (also called Iraklion), a city of about 125,000, is, by one guidebook’s description, “astonishingly ugly.” They got that right. Badly damaged by German bombs in World War II, it is an eyesore of blocky concrete buildings, noisy and congested. So why had I come?

It wasn’t to lie on the white sand beaches of Elounda on the Gulf of Mirabello an hour to the east or at Ayia Pelagia or other nearby magnets for sun worshipers. This was March, not yet beach season in this, the largest of the Greek islands. Nor had I come to hike the Samaria Gorge, one of the longest in Europe.

I had come mainly to see the restored Minoan palace of Knossos three miles southeast of Heraklion and to see the incredible treasures of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

Two days would do it, and then off to Chania — arguably the prettiest town on Crete — for another two days on this visit, piggybacked with a pre-Olympics trip to Athens.

Somnolent villages still exist on the southern, less tourist-trammeled side of Crete, I’m told, but the north coast, with the island’s three major towns — Heraklion, Chania and Rethymnon — is anything but quaintly ethnic. That disappeared when the number of annual visitors to this island 100 miles south of the Greek mainland reached 3 million.

Less than an hour by air from Athens and served by commercial car and passenger ferries, Crete saw tourism jump 50% between 1990 and 2000, taxing its infrastructure and choking its towns with traffic. The physical degradation of coastal resorts, with their cheap holiday packages, has been matched by the dilution of traditional island culture.

If an island vacation with beach time is your wish, there are places just as pretty that are far closer to Los Angeles and where the spellings of place names is far less confusing. (You’ll see Chania as Canae or Hania, among others.) But if ancient artifacts are your thing — and you’re headed to Athens for the Olympics, which are to open Friday — Crete is certainly worth a look.

Checking into Lato Hotel in Heraklion — a city that will host some of the Olympics’ soccer contests — I was overjoyed to hand the bellhop my car keys and let him try to find a space on the street. The refurbished boutique hotel has contemporary décor, a restaurant and an inviting bar. My twin-bed room, done in champagne and charcoal and with a balcony overlooking the Venetian harbor, was perfectly pleasant.

For dinner within walking distance, the desk clerk recommended Fos Fonari. When I arrived about 9, there was only a handful of diners, but by 11 the restaurant was filling rapidly. A table opposite mine was claimed by a young man and five mini-clad women sharing platters of food between cellphone chats.

The chef’s special salmon baked in vodka cream sauce with raisins and celery was tasty. And then I presented my credit card. Fos Fonari doesn’t take credit cards, and I had no cash, so my waiter doffed his apron and led me down the street to an ATM.

Getting an early start the next morning, I snagged the last free parking space at Knossos. In summer, the crowds are huge, but in March I encountered only a few clusters of tourists, including several large school groups. As I walked the paths, I tried to envision the 1,500-room palace that once stood on the site.

In Greek mythology, Knossos was home to King Minos, who was married to Pasiphae. Her carnal caper with a white bull produced the Minotaur, a ferocious half-man and half-beast that was locked up at the palace and fed men and maidens.

When Theseus, son of Athenian King Aegeus, came to slay the beast, Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell for him and helped him escape afterward. The lovers fled together, but he later dumped her.

The Knossos that visitors see today is largely a reconstruction built on the ruins of an 18th century BC Minoan palace destroyed by fire in the mid-15th century BC. The controversial interpretation of what once existed is largely that of Sir Arthur Evans, an Englishman who bought the site and began digging about 1900.

The fact that one doesn’t know for sure what one is seeing doesn’t detract greatly from the experience. (For example, what Sir Arthur thought was an open-air theater later scholars thought was a reception area for VIP guests.)

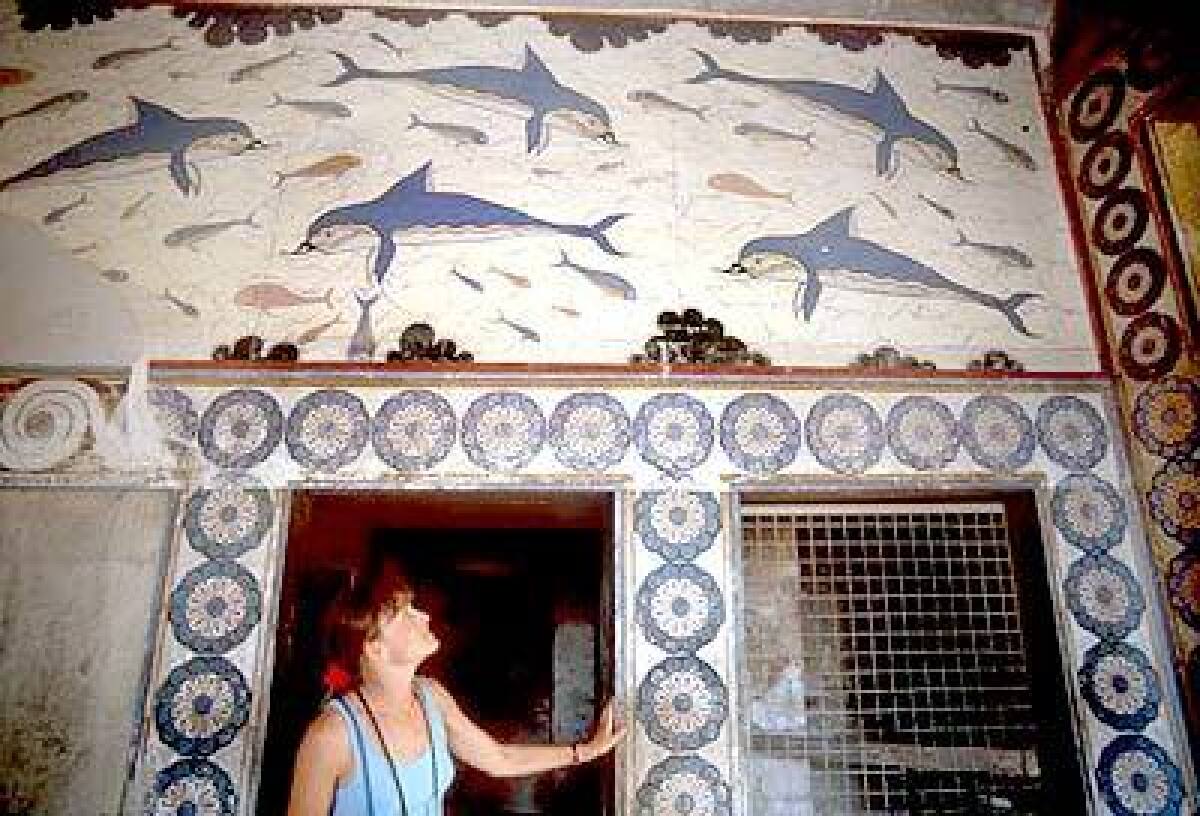

Although not totally authentic, Knossos is totally fascinating — from the clay bathtub in the queen’s apartments to the carved stone throne of King Minos.

Leaving Knossos, I ate a quick lunch at a nondescript cafe just across the road before heading back to town and the Archaeological Museum. It’s a good idea to see Knossos before visiting the museum; many of the palace treasures, as well as some of its heavily restored frescoes, are here. It’s been suggested that the palace site was never vandalized because would-be thieves were put off by the myth of the Minotaur.

It takes at least two hours to see everything, but if you’re short on time, head straight for Room IV, where you’ll find a carved black stone bull’s head with jasper eyes and gilded horns, a ritual vessel from Knossos.

Here, too, are the faience figurine of a bare-breasted snake goddess and an exquisite carved ivory bull-leaping acrobat, both from Knossos. In Room VII, I was so taken with the gold pendant of two bees holding a honeycomb (it’s from a Minoan tomb) that I later bought a silver replica at a shop across the street.

Upstairs is the so-called “toreador fresco” from Knossos, depicting a man somersaulting over a charging bull as one woman holds the horns and another stands ready to help.

Back outside, I headed for the pedestrian streets off Plateia Eleftherias. Heraklion’s young set filled the tables at sidewalk cafes along Daedalou and Korai streets; at 5 Korai I found Loukoulos, a lovely restaurant in an old townhouse.

Although alone, I was shown to a table for five and showered with attention. The cuisine is more Italian-Mediterranean than Cretan, and my beef entrée was fine but not memorable. If you go, be aware that rock music from a nearby venue penetrates the back windows of the dining room; choose a table in the pretty front garden.

In the land of Zorba

The next morning I hit the E-75 for Chania. The road, the new national highway, is four lanes much, but not all, of the 85 miles west to Chania. On narrower stretches, I hugged the shoulder, as I’d been advised to do by an Athens taxi driver who feared for my safety behind the wheel.About halfway between Heraklion and Chania, I turned off at Rethymnon, which has appalling traffic but — once you fight your way into the historic core — morphs into an old town rich with Turkish minarets, Venetian facades and narrow streets with shops selling jewelry, leather and lace.

At a seaside open-air taverna in the shadow of the imposing Venetian fortress at the harbor, I bundled up against the chill and ate just-OK spaghetti with wild mushrooms — spaghetti is a standard menu item hereabouts — and bitter dandelion greens splashed with olive oil and lemon.

Back on the highway, I passed roadside shrines, a few goats and even a sheepherder with his flock. Just west of Rethymnon, big new resort hotels have sprung up along the coast. I’d seen in a guidebook the name of the village — Kokkino Chorio — where Zorba lived in “Zorba the Greek,” the 1964 film based on a novel by Crete native Nikos Kazantzakis. When I saw a road sign for the turnoff, it was irresistible.

Up and up I drove on a narrow, winding mountain road, my enthusiasm flagging with each blind curve. When I learned I still had 4 kilometers to go — on an even narrower road with huge potholes — I turned back.

Map in hand, I drove into Chania and headed for hotel Casa Delfino.

My map forgot to mention the auto-free streets, so I found myself driving in circles.

Finally, I parked near the harbor and walked 15 minutes to the hotel, where I described my situation to Stella, the clerk, who called Costas, the off-duty clerk, and asked him to get on his motorbike, meet me at my car and lead me to the hotel’s parking area. Costas was a lifesaver; he even schlepped my bags up the 49 steps to my room.

Although I’d booked one of the lesser rooms (the suites are fabulous), I loved the place, which is in the heart of the old town, just removed from the bustle of the seafront promenade.

From my room, I looked down on a beautiful gated courtyard and weathered red-tile roofs. Candles flickered on tables as I enjoyed a cool drink in the courtyard.

Dinner was at Dino’s, a long-established seafood restaurant at the less touristy Outer Harbor. Nothing fancy — bare wood tables and half-hearted décor. I put away a mezede (appetizer) of grilled red peppers and a plate of the three biggest shrimp I’ve ever seen, grilled in their shells. All very tasty.

Casa Delfino is just off Theotokopoulou, the prettiest of the old town’s cobbled pedestrian streets.

It’s named for Crete’s most famous son, El Greco (born Domenikos Theotokopoulos). I poked through shops selling jewelry, sponges, spices and ceramics before heading for the esplanade, where annoyingly persistent touts drummed up business outside cafes.

Busy Khalidon Street is the main link between harbor and old town and, at the harbor end, is lined wall to wall with tourist shops selling plastic worry beads and other trinkets. I saw no Greek fishermen’s caps but lots of baseball caps with logos of U.S. teams. (Serious shoppers might check out Mitos gallery at 44 Khalidon for high-quality jewelry and ceramics by Greek artisans.)

A left turn off Khalidon led me to Skridloph, the leather street, a blur of shops selling handbags and sandals. (Not all items are made in Greece, so check.) Continuing toward the new town, I made my way to the public market, which occupies a vast cruciform-shaped 1911 building at Plateia S. Venizelou. Fishmongers were selling whole octopuses, and butchers hawked pigs’ feet with legs attached. Vendors sold spices, fresh vegetables and ouzo, the strong anise-flavored aperitif. Tantalizing smells wafted from little cafes.

For some inexplicable reason, I paid $5 for a pair of candleholders that are miniature ring-shaped Greek wedding cakes. The vendor suggested I douse them regularly with fly spray, lest creatures hatch inside the dough. Once home, I popped them in the freezer. So far, no bugs.

My wanderings then took me up the hill above the harbor to the Kastelli neighborhood, which was particularly hard hit by World War II bombings. It was astonishing to see homes built right into the ruins of bombed-out buildings.

Back at the harbor, I checked out some other old town hotels. Around the corner from the Naval Museum, Pension Thereza on Angelou Street had posted a sign saying to pick a room key and take a look. For those with a modest budget and strong legs, this is a find. There’s a little lobby with stone walls and, up 44 spiral stairs, is Room 1, a charmer with a double bed, a loft with two singles, bath, air conditioning, TV and a harbor-view balcony — all for about $48 a night. At Casa Leone, in a 600-year-old house with a lovely courtyard, a clerk showed me two suites, both spacious and very nice. Room 2, with harbor views, rents for about $133 in season.

The Greek way

Having worked up an appetite, I headed for Tamam, an old town restaurant in a building that once housed the cold-plunge pool of a Turkish bath. There are tables in the sunken area and others in the narrow space rimming it. One steps gingerly so as not to fall in. Every table was taken, so I left my name and killed an hour at an Internet cafe. I loved Tamam, with its piped-in harem music and vintage ad posters. (Note: This is definitely not a no-smoking zone.) My meal — lamb with yogurt, raisins and spices — was wonderful. At 12:45 a.m., as I sipped a complimentary raki, a fiery distilled grape drink, people were still arriving. No, the waiter told me, they didn’t have the next day off; this is simply the Greek way.On my last day, I had a few hours to explore the Akrotiri Peninsula before checking in at the airport, which is on the peninsula about nine miles from town.

The peninsula has nice beaches and some awful new vacation villas. Following the signs to Stavros, I found a pretty, sandy cove sheltered by a tall cliff. In my imagination, I saw Anthony Quinn, the Greek peasant, teaching Alan Bates, the reserved Englishman, how to dance — just as he had at this very spot in “Zorba the Greek.”

It was Crete as I prefer to think of it.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Searching out the island’s best

GETTING THERE:

From LAX, Heraklion is served with connecting service (change of planes) on Lufthansa, Air France, Air New Zealand, Air Tahiti Nui, United, British Airways and KLM; many connect to Olympic Airways to Crete. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $1,180.

TELEPHONES:

To call the numbers below from the U.S., dial 011 (the international dialing code), 30 (country code for Crete) and the local number.

WHERE TO STAY:

Casa Delfino, 9 Theofanous, Chania; 2821-087-400, fax 2821-096-500, https://www.casadelfino.com . Suite hotel in lovely 17th century Venetian mansion in quiet old town location at harbor. Seasonal rates begin at $143.

Lato Hotel, 15 Epimenidou, Heraklion; (800) 577-9449 or 2810-228-103, fax 2810-240-350, https://www.lato.gr . Nicely renovated boutique hotel and restaurant overlooking old Venetian harbor. Seasonal rates begin at $137.

Porto Veneziano Hotel, Akti Enoseos 73132, old Venetian harbor, Chania; 2821-027-100, fax 2821-027-105, https://www.porto-veneziano.gr . Attractively updated Best Western at quiet end of harbor. Seasonal rates begin at $114.

WHERE TO EAT:

Tamam, 49 Zambeliou, Chania; 2821-096-080. Atmosphere abounds in this restaurant in a former Turkish bathhouse, and the Greek food is very tasty. Dinner entrees from $10.

Dino’s, 2 Akti Enoseos, Chania; 2821-041-865. Long-established restaurant overlooking harbor. Excellent seafood, with dinner entrees from $6.

Loukoulous, 5 Korai, Heraklion; 2810-224-435. Elegant dining in restored mansion or romantic courtyard. Large and varied menu. Dinner entrees from $10.

Fos Fanari, Plateia Agiou Dimitriov, Heraklion; 2810-342-245. Neighborhood restaurant serving well-made Greek specialties, with entrees from $6.

TO LEARN MORE:

Greek National Tourist Organization, (212) 421-5777, https://www.greektourism.com .

— Beverly Beyette

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.