While cap-and-trade funds stay mired in debate, businesses feel the hit

- Share via

Reporting from BURNEY, California — For more than two decades, Dianne Franklin’s logging business hummed in harmony with the power plant next door.

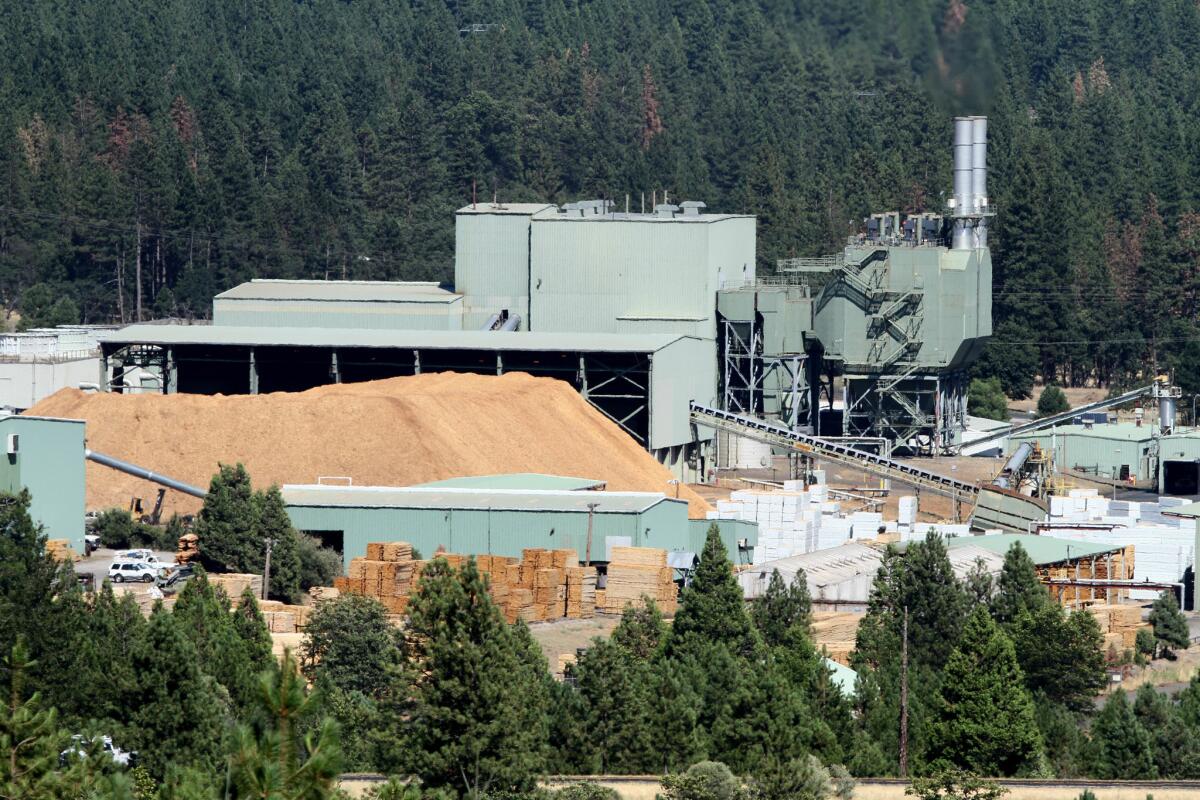

Her employees cut and processed trees from forests surrounding Mt. Shasta and sent biomass waste — giant mounds of wood chips — to her neighbor, which burned the byproducts to generate electricity. The plant piped steam her way to dry planks of wood used to build homes and furniture.

But early this month, Franklin got an ominous notice: The plant, Burney Forest Power, would shut down in 60 days. With no market for her waste product and no steam to dry her wood, there’d be no need for new logs, trucks to transport them or operators to run the mill. Pink slips for her 120 employees were all but certain.

There could have been a lifeline for California’s struggling biomass plants, and by extension, companies such as Franklin’s. The state’s landmark cap-and-trade program, in which businesses purchase permits to pollute, has generated billions of dollars in revenue — all of which must be spent on ways to reduce greenhouse gases. That could mean building the bullet train, weatherizing old homes or supporting biomass, which Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration endorsed in a report this year as offering environmental and economic benefits.

But for two consecutive years, Brown and top state lawmakers have been at a standstill on how to spend cap-and-trade money. More than a billion dollars sits unallocated, as climate policy emerges as the most politically fraught issue consuming the Capitol in a state that prides itself on its environmental leadership.

In back-to-back years, the Legislature has considered ambitious proposals to boost renewable energy, slash gasoline use and broaden the state’s signature greenhouse gas emission goals. Through it all, the unspent money has hovered as potent leverage for Brown and legislative leaders, dangling the possibility of loosening the cap-and-trade purse strings to entice lawmakers who have balked at backing aggressive new climate laws.

Now, with two weeks left in the legislative session, there has been a renewed push to spend at least a portion of the auction revenues. But lawmakers see missed opportunities in jump-starting the efforts to reduce greenhouse gases.

“It’s not like a savings account that we put in the bank and wait for retirement,” said Sen. Fran Pavley (D-Agoura Hills). “Climate change is urgent now.”

Assemblyman Brian Dahle of Bieber, whose northern district is home to Burney Forest Power, also had a sense of urgency. The Republican, who does not support the state’s climate program, proposed a bill last year that would direct some of the cap-and-trade money to help offset the operating costs for biomass plants, hoping to stave off a shutdown.

He thought his bill aligned with California’s pollution-reduction goals by supporting a renewable way to generate electricity, and through reducing the risk of a catastrophic wildfire by clearing out the state’s large number of dead trees.

One year later, his bill has languished in the Legislature, trapped in the budgeting black hole of cap-and-trade. And in Burney, where Franklin was forced to lay off her workers, the 71-year-old teetered between shock and anguish.

“This was not supposed to happen,” she said, her eyes welling before breaking into tears. “I just want to keep everything going. This is my life.”

California began conducting cap-and-trade auctions in 2012, raising about $4 billion to date. Sixty percent of the proceeds are directed each year to certain projects, including the bullet train, transit and affordable housing programs. The rest is haggled over in the budget process.

Brown and the Legislature agreed on spending plans for that money in 2013 and 2014. So far, $1.7 billion — including automatic appropriations for last year’s budget — has been sent to more than two dozen programs. The administration estimates that will ultimately reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 14 million metric tons — roughly equivalent to one year of emissions from nearly 3 million passenger vehicles.

Cap-and-trade spending plans were not included in the last two budgets, and about $1.4 billion is sitting unallocated in the program’s account.Meanwhile, ambitious new climate policies have had a rocky reception in the Legislature. Lawmakers approved a bill last year to increase energy efficiency and ramp up the use of renewable electricity in the state, but a controversial proposal to cut gasoline use in half was nixed after facing resistance from business-friendly Democrats.

This year, there have been uphill efforts to extend the state’s emission reduction goals and shore up the cap-and-trade system, which faces legal challenges and market uncertainty. Revenue from the auctions plunged in May, causing the program’s anxious backers to push for speedy legislative action. The revenue decline has made some wary about drawing down cap-and-trade funds.

Still, there has been a raft of bills proposed since last year specifying how auction proceeds should be spent. They come from a cross-section of legislators — Democrats and Republicans, urban dwellers and rural residents, those from wealthy enclaves and the state’s poorest communities.

The measures would have earmarked money to boost alternative fuels and build solar projects in needy neighborhoods. They would have paid for cleaner transportation in state ports and new school buses in poor districts. Nearly all have sputtered before reaching the governor’s desk.

“We are getting to that point where programs are running out of money,” Assemblyman Jimmy Gomez (D-Echo Park) said of what has been affected, including a state initiative offering rebates for electric cars.

Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Los Angeles) and Senate leader Kevin de Len (D-Los Angeles) said they want to see at least some money appropriated before the end of the month.

“There’s no reason whatsoever we can’t start right now,” said de Len, adding that he was working with Rendon “to persuade the governor [about] the wisdom of pushing these dollars out the door so they can do good for Californians up and down the state.”

Asked if the money had been held as leverage to drum up support for climate bills, de Len demurred: “That’s a question you’d have to ask the governor.”

Brown’s office did not comment on cap-and-trade funding. A spokesman referred to a statement by top Brown aide Nancy McFadden this month vowing the state would extend its climate goals “one way or another.”In Shasta County, the rumors of the biomass plant’s shutdown spread quickly through the Sierra, on Facebook and truckers’ CB radios.

“You can’t go through town without hearing about it,” said Danny Osborne, the sales manager for Shasta Green, Franklin’s company.

Dahle knows the ripple effects that are coming. Fifty miles away, his hometown of Bieber went through an economic downward spiral 15 years ago when a local sawmill shuttered. His office estimates that 275 direct jobs will be lost from the planned shutdown of two local plants, a substantial loss for Burney, with its population of just over 3,000 people, and similarly sized nearby towns.

Dahle acknowledges his measure was a short-term fix for a much broader problem. California’s biomass industry, which had more than 60 facilities at its peak in the early 1990s, has declined significantly as the state shifted its subsidies to cleaner ways to generate electricity, such as wind and solar.Dahle had hoped to use cap-and-trade money to subsidize the facilities’ purchase of biomass material, giving them some breathing room until they can negotiate more favorable contracts with utilities that buy their electricity.

“Once they shut down, they don’t come back,” Dahle said.

Biomass plants are struggling at a time when their services are likely to be in high demand. Prolonged drought and a bark beetle infestation have killed at least 70 million trees, creating a tinderbox for a potential calamitous wildfire. But without biomass facilities to process the timber, there is nowhere for the dead trees to go — except controlled open burns, which spew carbon into the air.

Dahle’s proposal had its detractors: Environmental groups such as the Sierra Club opposed the bill, arguing there are better ways to offset the effects of climate change. And others including the California Chamber of Commerce object to spending cap-and-trade funds while a challenge to the program’s legality works its way through the courts.

Nevertheless, Dahle’s bill glided through the Legislature last year without a single “no” vote in any policy committee or on the Assembly floor — until it was shelved in the Senate. Dahle attributes the holdup to the political gamesmanship behind budgeting that cap-and-trade money, but struggled how to explain that to constituents like Franklin.

“They don’t understand how the politics of the whole place works,” Dahle said. “If you run a bill, there’s leveraging and there’s all kinds of factions that happen.”

Dahle is sharply critical of the state’s climate policies and often hears the argument that it’s hypocritical to angle for cap-and-trade money when he is disinclined to back the program. But he said Brown and top lawmakers do themselves no favors in making their case by, as Dahle sees it, hoarding the money.

“If you’re going to ask me to vote for something, wouldn’t you spend some of the money to show me what you’re going to do with it?” he asked. “I think it’s kind of hard to use the whip all the time. Sometimes you need to use the carrot.”

ALSO

An oil industry lobbyist wrote the request to audit the state’s main climate change agency

Regulators holding cap-and-trade auction as lawmakers consider next steps on climate change

With climate legislation stalling, Jerry Brown looks to potential fight at the ballot box