When blood fizzes

- Share via

In the main cabin of the boat Sundiver, braced against the rock of ocean swells, two divers listen. They listen to the gurgle of their blood as it courses through the large veins of their shoulders. They listen for the sounds of trouble. They listen to the result of descending into the winter Pacific twice as deep as the maximum for ordinary recreational scuba — and maybe deeper even than that. They’re not telling exactly.

They listen to themselves fizz like a couple of oversize champagne bottles.

“Flex,” says Kendall Raine.

His dive partner, John Walker, makes a fist and flexes his arm.

Raine wears earphones attached to a Doppler ultrasound monitor. But the amplified sound overpowers the earphones and can be heard by everyone in the cabin: the crackle-static of bubbles.

“Ohhhh,” says Walker, his eyes widening at the noise coming from inside his body.

Raine moistens the probe of the monitor and applies it to his own shoulder. Again, crackle-fizz.

“That’s a fair amount of bubbling,” Raine deadpans. He jots the pair’s “bubble score” in his decompression log.

If, by contrast, you listened to the sound of your blood, you would hear no fizz. Bubbles are what come from daring the deep, staying long, breathing hard. Tiny bubbles in the blood are the enemy. Too many, and they will cripple or kill you or, at the least, send you on a breakneck race to the nearest emergency recompression chamber. They are what make tech diving especially well, adventuresome. That, and the ethereal darkness at great depth, and the cold, and the eerie tricks that happen in the mind when one ventures beyond the reach of any possible help, down to the bottom, down where the whale songs travel for miles and miles to places that no one — ever — has seen before.

Sunken sub

Investment banker Kendall Raine wears the face of a man younger than his 44 years. A resident of Malibu, he has a boyish, cheery, fresh-scrubbed look to him. Coincidentally, something of the same can be said about his partner, 42-year-old Westminster elevator repairman John Walker, who carries himself with an easy smile and gentle eyes that show no trace of world-weariness. Together, they brighten up the cabin of the 54-foot Sundiver as it bobs in the swell off San Pedro Bay.

These two Southern Californians have a combined 60 years’ experience underwater and a couple of decades exploring the rarefied, experimental realms of mixed-gas deep technical diving — wreck diving and cave diving. No doubt you could raise an argument about how many sport divers hereabouts could equal their experience — maybe 50, give or take. Suffice to say that when Sundiver’s skipper and underwater wreck hunter Ray Arntz wanted a team to go deep and survey the recently discovered wreckage of a sunken German submarine, he selected these two.

“I’ve been testing people for this dive for 10 years,” says Arntz, whose occupation is to run scuba charters aboard his Long Beach-based Sundiver. “They’re the best.” Besides, he could count on them to keep secret the location of the wreck, UB-88. Scuba diving is our ticket to the last frontier. Never mind those banalities about there being nothing left to discover on this planet. Most of our world is underwater and unexplored.

But even at its most easygoing, scuba requires a wary understanding of what happens to the body as the diver descends. The breathing regulator “regulates” the pressure of air released into the lungs to equal the surrounding water. Because of water’s weight, a diver at 33 feet is breathing air at twice the pressure of the surface atmosphere — meaning twice as many molecules of oxygen and nitrogen are inhaled with each breath. At 66 feet, the pressure is three atmospheres, and so on.

Nitrogen, which makes up 79% of air, is inert at surface pressures. But as one descends and breathes more of it, the gas accumulates and can cause a euphoric condition that interferes with judgment. This is known as narcosis, or rapture of the deep. What’s more, this buildup of gas waits in the blood like carbonation in a pop bottle. If a diver surfaces too rapidly without “offgassing” surplus nitrogen, the blood fizzes just as a shaken carbonated beverage does if opened too quickly. The explosion of these bubbles can cause permanent tissue damage and sometimes death. The accompanying pain in the limbs and abdomen is unbearable, bending a diver over — as in the “bends.”

For this reason, standard scuba certification limits divers to a depth of 100 feet — 130 feet at the extreme.

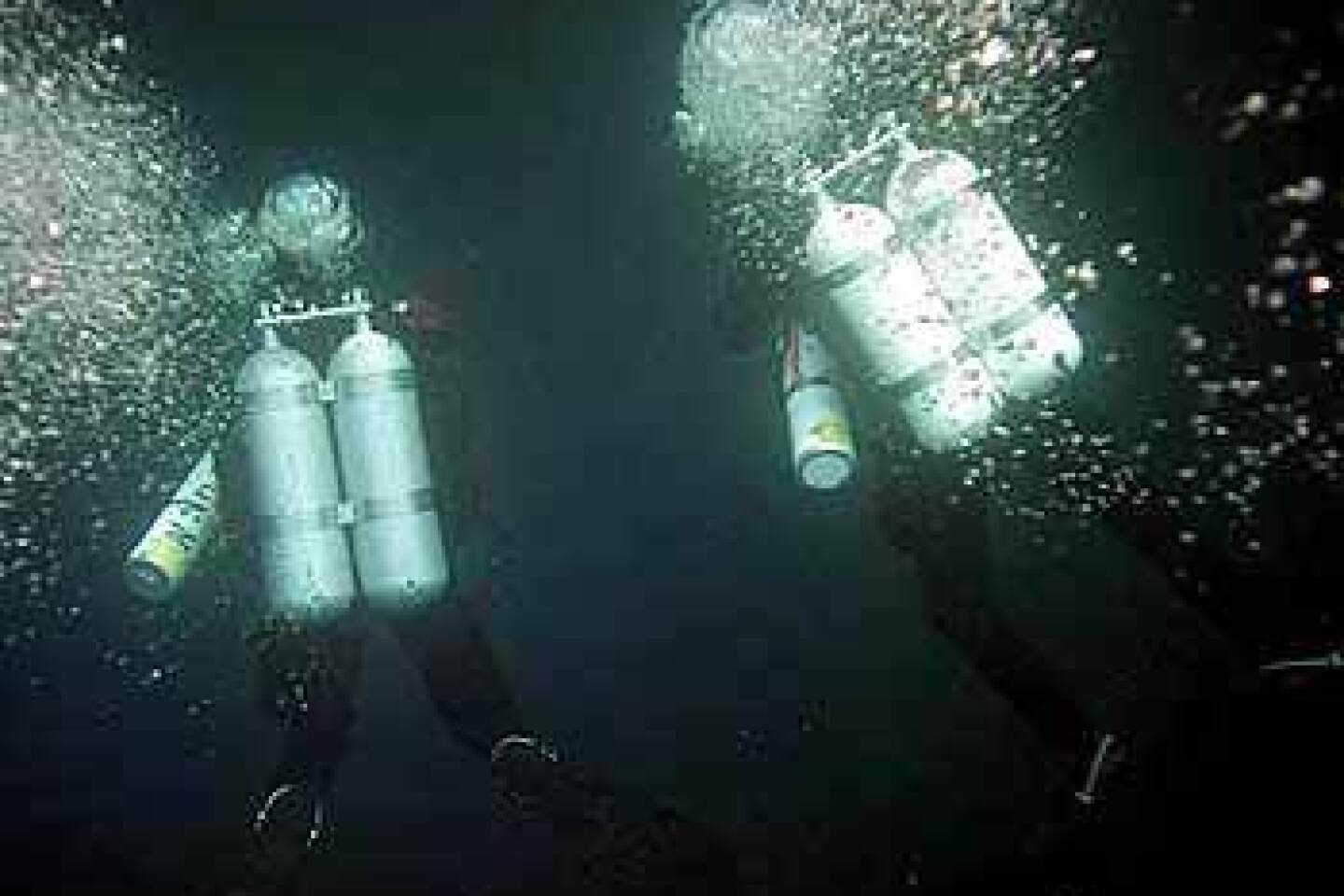

Tech divers venture three times as deep, or even more. Typically, they forgo “air” in favor of their own otherworldly mixes of breathing gases. They reduce oxygen and nitrogen and add inert, “friendly” helium to give them plenty of bottom time at depths, like UB-88’s, where pressures are something like nine atmospheres. For the ascent, they carry decompression tanks filled with other breathing mixes to speed up offgassing. They call on computer programs and individual experience to draw up a dive profile they trust to bring them slowly to the surface in stages — without bubbling over.

Disharmony

Raine sits on Sundiver’s aft deck, burdened with more than 200 pounds of gear: twin 130-cubic-foot tanks of helium-oxygen-nitrogen trimix, a tank of oxygen-enriched air or nitrox for decompression when he ascends to 70 feet and another of pure oxygen to be used at 20 feet, plus a bottle of argon gas that he uses to fill his dry suit — argon molecules being large and offering superior insulation against cold. He carries a spare mask, an extra regulator, a spool of nylon line, a high-intensity canister light, two backup lights and a waterproof notebook on which is written his decompression profile. On one wrist he wears a compass and dive watch; on the other, a bottom timer. His dry suit is fitted with a discharge valve so he can expel urine.Tech diving is not an endeavor that places man in harmony with nature.

Next to him, Walker is outfitted in a virtually identical array. If something goes wrong, each diver will know his partner’s rig without a second thought. The only difference in their equipment is that Raine will carry a still camera; Walker will shoot video.

An hour offshore, under sodden, windless fog, Arntz maneuvers Sundiver by GPS to the precise location atop UB-88. A lead weight is dropped overboard, attached to a line and a surface buoy. That will guide the divers down.

Working with Arntz, amateur archeologist and team leader Gary Fabian, a Southern California recreational fishing enthusiast, located the wreck last summer after searching for more than a year. Raine and Walker made their first dive to the World War I submarine last August. This will be their second.

Having sunk a dozen or so allied vessels in combat, UB-88 became a spoil of war, seized after the armistice and studied by U.S. naval intelligence. It was then displayed at American ports in a government campaign to sell Victory bonds. Finally, the 182-foot vessel was stripped and towed from San Pedro harbor. On Jan. 3, 1921, a Navy live-fire exercise sent it to the bottom. It is believed to be the only German U-boat off the West Coast, and in recent years it had become a prime target for wreck searchers.

“Juan, what’d ya say?”

Walker sounds the ready.

Helped to their feet, the overburdened divers shuffle and clang to the side of the boat. Clutching as much of his gear as he can, Raine takes a stride and plunges into the larger realm of our world. Walker follows. From the concussion of entry, they bob back to the surface and signal “OK.” They paddle to the buoy, nod and disappear into the inky green, sending up a cascade of chrome bubbles.

Strangely, the dense pressure of water is also the medium that releases the diver from gravity. The two descend at something like 50 feet a minute, extended horizontally, facedown, weightless. At the surface, the temperature of the water is 59 degrees.

Cold, claustrophobic

Sharks, entanglement, catastrophic equipment failure, disorientation, strong currents — tech divers face the same dangers that ordinary divers do, compounded by the challenges of accelerated decompression. The gravest threat, though, exists just inside the facemask, in the diver’s head: self-control.The coastal Pacific is murky, claustrophobic, cold. Communications are by hand sign alone. As they descend, only the stringlike buoy line, slicing through the featureless green-gray, offers these divers something by which to orient themselves. The normal reaction to such conditions would be anxiety. But anxiety is the beginning of much of what goes wrong in diving. If you’re tense, a problem can trigger panic. In tech diving, that is the road to doom. Whatever exhilaration and thrill that accompanies a deep descent must wait until later. For the interval underwater, those emotions must be restrained. A diver seeks inner tranquillity in an inimical environment.

Raine and Walker concentrate on their breathing. Inhale, hiss. Slow. Exhale, gurgle. Slow. An old saying: A dive that starts right, ends right. The first minutes set the tone. That’s when you must achieve the trance. If your breathing is relaxed, you are relaxed. There’s no faking it now.

At the same time, however, there are important considerations: Will currents carry them away from the wreck? And what about visibility? The water can be murky on the surface and clearer down deep, or the other way around. You never know. They watch their depth gauges and the clock. They inspect each other carefully for anything out of kilter, like a gas leak. They equalize the pressure in their ears and sinuses. They inflate their dry suits with shots of argon to compensate for the increasing pressure of water. They listen to their breathing.

When he was a boy, Raine was transfixed by “Sea Hunt” on television. In 1971, he saw the shark movie “Blue Water, White Death,” precursor to the more famous “Jaws.”

“Diving — I thought it was the coolest thing a person could do,” he says.

At 9, he learned how to do it. Later, he studied mixed gases. For two years, he trained to dive the wreck of the passenger liner Andrea Doria, which lies on its side in treacherous waters off Long Island, N.Y., at a depth of 255 feet. In 1995, he made the descent. Adventure writers often call this the “Mt. Everest” of diving, for the Doria, like Everest, periodically kills those who dare its challenge. Off Northern California, he dived to the deep wreck of the paddle-wheeler Brother Jonathan and helped recover $5.3 million in gold coins for the team that held salvage rights. Raine’s deepest dive has been 350 feet.

Now, Raine and Walker approach the bottom of San Pedro Bay. The water temperature is 51 degrees. They are deeper than 230 feet.

That’s all they’ll disclose. They don’t want to be responsible for tempting less experienced divers to venture here. For one thing, the UB-88 is thought to contain an unexploded demolition charge. For another, too many wreck divers are souvenir hunters.

There it is.

By chance, the visibility turns out to be good — perhaps 50 feet. The shadowy tubular profile of UB-88 lies upright. Not in 82 years has another human eyed this vessel. Never, it is safe to say, have people beheld this piece of the sandy bottom of the continental shelf. The divers cache their decompression bottles. They kick and begin their circumnavigation.

Odd thing, but color changes according to depth. Water filters out red light at only 15 feet. Orange disappears at just over 50 feet. Violet is absorbed at 100. This deep, everything is rendered in shades of black and dim blue.

Then the divers illuminate their path with artificial lights. The drab old sub flares incandescent pink, as pink as a flamingo, with streaks of purple and veins of green — the psychedelic glow of sea anemones and other homesteading organisms that frost every inch of the submarine. Schools of sardines glitter in the background. Scowling rockfish hold their place in nooks and breaches in the vessel’s carcass. Baitfish dart in and out of sight.

Raine has seen many shipwrecks, but few this outrageously beautiful. He ponders the paradox: “This was a weapon of mass destruction. It did its work attacking civilian as well as military ships. And now it’s evolved from that awful purpose to become a living organism. It’s a ruin — a ruin and renewal.”

Serene

“It is quite serene. Besides bubbles, there are no sounds of engines, no people yakking in your ear. It is spectacular.” Walker is describing the lure of diving deep. He taught tech diving for 10 years. He dived to the wreck of the Civil War ironclad Monitor in 230 feet of turbulent water off Cape Hatteras, N.C. He has recovered bodies for law enforcement. His deepest dive took him to an astonishing 385 feet — too deep for sunlight to produce photosynthesis in plants. More recently, he and Raine penetrated 2 miles into an underwater cave system in Mexico.Serene?

Only by the most audacious standards.

Spectacular?

Most of us will have to take his word for it.

The history of deep diving fairly brims with tales to scare away the fainthearted: divers who inexplicably vanish, divers who run out of breathing gas and shoot to the surface knowing they will be overcome with the bends and probably die, a father and son who perish in the pursuit of souvenir chinaware from a shipwreck, the roll call of two dozen or so divers killed on the Andrea Doria.

Reliable statistics of these incidents are nonexistent. DAN, the Divers Alert Network, maintains the premier databank of diving injuries and fatalities, but Dr. Richard Vann, its vice president for medical research, said: “We just don’t have very much on deep diving or tech diving and that’s been a real problem.” In one DAN study of experienced divers, those who descended deep in cold water to explore wrecks recorded nearly 30 times the rate of decompression injuries of those who dived in warmer water off live-aboard dive charters. But that tells the tech diver little.

Most experts in the field agree on three things: (1) Deep diving is becoming safer as more is learned and as equipment gets better; (2) the blasé deep-diving “cowboys” who rely primarily on bravado instead of science are incrementally removing themselves from the gene pool; and (3) what is known about safe decompression from very deep depths is still surprisingly sketchy in both its short- and long-term consequences.

Put another way, anyone with a few weekend training sessions can descend to 300 feet, but very few understand how to return alive, and even they face uncertainty.

“We know more about being in outer space than about being underwater,” says David Mount, general manager of the Florida-based IANTD, the International Assn. of Nitrox and Technical Divers.

Or, as Walker jokes: “The dumber you are, the deeper you can go.”

So what’s the point of taking the dare?

Raine pauses and delivers one of those schoolteacher looks that you get for asking a question when the answer is self-evident.

“Adventure,” he says, smiling.

Numbingly tedious

Twenty-five minutes into the dive, Raine and Walker retrieve their cached gas bottles and head for the surface. For the next 80 minutes they will inch their way up, pausing at 18 predetermined stages for differing intervals to offgas. It is numbingly tedious. “Awful,” says Raine. Warmth, sunshine, hot coffee, your friends — all of them are less than a block away, just overhead, yet unreachable on that other part of the planet.Suddenly, music.

The ocean rumbles with the songs of distant whales. These unearthly vibrations do not just reach the divers’ ears but physically pass through the liquid of their bodies. Water filters light but enhances sound, particularly low-frequency sounds like the symphonies of whales — which can travel for miles through a thermocline of equal-temperature water.

Dangling mute in open, featureless ocean, they are touched as if by creation itself.

Long before the pair surfaces, two support divers splash into the water. Both are qualified tech divers. Fred Colburn is a full-time diving instructor from San Pedro; Scott Brooks is a Palos Verdes CPA and dive instructor. They carry extra bottles of breathing gas as a precaution. They will meet the deep divers at 70 feet and assist if necessary, or in this case, offer reassuring companionship.

A while later, yet another diver unexpectedly joins the team. A lone — perhaps lonely — sea lion dive-bombs and playfully circles the four men who are sending up glimmering clouds of bubbles.

Then they are back. Gravity takes hold once again. The deep divers climb aboard awkwardly and lumber to a bench. They strip to their insulated long johns, filling bins with dripping rubber and steel. Their movements are slow now. They are chilled. Their faces are pale, slightly drawn, creased by the seal of their masks. They don’t look quite as boyish anymore.

Their verdict: “Great dive.”

A half-hour later, they begin the ultrasound scans of their blood. Raine finds the residual bubbling more than he expected, enough to be of “borderline concern.” For the next few minutes, he breathes from a bottle of pure oxygen to speed the cleansing of his blood. He and Walker will not exert themselves or lift anything heavy for the rest of the day to reduce the chance of post-dive problems.

As the Sundiver heads home, the two begin making mental adjustments to their decompression profile, adding another layer of experience to the science of exploration. There is the next dive to consider. The deep beckons.

John Balzar is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.