Setting a Modern standard

- Share via

“Stand here,” directs Edward Killingsworth, indicating the middle of the master suite, or, as he calls it, “the magic spot.”

Each 90-degree turn you make yields unobstructed sight lines: to the front, a perfectly centered bed; to the left, a glass alcove; to the right, the interior garden room; to the back, through the glass dressing room, an intimate outdoor garden. This spatial experience — a graceful interplay and uninterrupted flow between areas — repeats throughout the house the architect built for his family in 1961.

It would be easy to pigeonhole the Killingsworth residence as midcentury Modern, with its flat roof, wood-frame construction, walls of glass and emphasis on indoor-outdoor living. But his timeless design transcends such typecasting.

As one of the last surviving architects of the Case Study House program, Killingsworth, 86, is a quiet hero in the architectural community. His whole career he has consistently been stable, modest, thorough and relatively unknown in comparison to his Southern California contemporaries. Along with well-known figures such as Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, Craig Ellwood and Raphael Soriano, he was one of a handful of optimistic, social-minded architects who tested unconventional concepts of plan, form and structure in residential architecture. Conceived by John Entenza, the editor of Arts and Architecture magazine, the Case Study Houses provided affordable yet progressive prototypes for living.

Emphasizing the technological innovations that defined Modern architecture, the architects implemented new industrial materials and open plans in their designs. Entenza discovered Killingsworth in 1950 when he drove past the young architect’s first solo project, a 743-square-foot residence-office for his in-laws in Los Alamitos, a suburb of Long Beach. The house cost $5,500 and was one of the first post-and-beam structures in Southern California. It was direct and simple, with a smart plan that included office space fronting the public street and a private living area in the back. Impressed by the design, Entenza invited Killingsworth to participate in the program. “I owe my life to John Entenza,” says Killingsworth.

In 1953, Killingsworth made two major decisions: With two partners, he started his own architectural firm, Killingsworth, Brady & Smith, and purchased a 1-acre lot in Long Beach’s exclusive Virginia Country Club area for $6,500. Killingsworth designed a master plan, but because funds were scarce he postponed construction for several years. Instead, the massive undertaking evolved, methodically, as a family project.

He graded the land and, with his wife, Laura, and his sons Greg and Kim, he planted more than 100 trees and shrubs, including massive olive, sycamore and eucalyptus trees.

For the first 10 years of his work life, Killingsworth focused on residential work in Southern California. He designed numerous award-winning and highly acclaimed Long Beach projects, among them the Opdahl House and the Frank House, Case Study House No. 25. In the early 1960s, he expanded his practice to include civic and commercial buildings. The completion of the Kahala Hilton in 1964 established him as a world-renowned hotel designer.

But with his family home, Killingsworth created a uniquely personal statement. The 3,200-square-foot residence has an open plan of beautifully proportioned, dynamic living spaces, with 12-foot-high ceilings and doors in most areas. Even with the high, expansive glass, the house feels unusually private, its street facade offering little indication of what lies within.

With only two bedrooms, two bathrooms and a study, the floor plan was — and still is — considered an anomaly, particularly with the large amount of land on which to build. Killingsworth designed his house for a family of four and abstained from devouring the land, providing only the square footage they considered necessary for living space. “It’s a very large small house,” Laura says.

The design of the boys’ bedroom offered a novel way to accommodate both privacy and flow. It could be divided into two sleeping areas and a joint study area formed by sliding panels that straddle the middle space. Another radical element was the design of the bathrooms: full glass walls with unobstructed views of the outdoors.

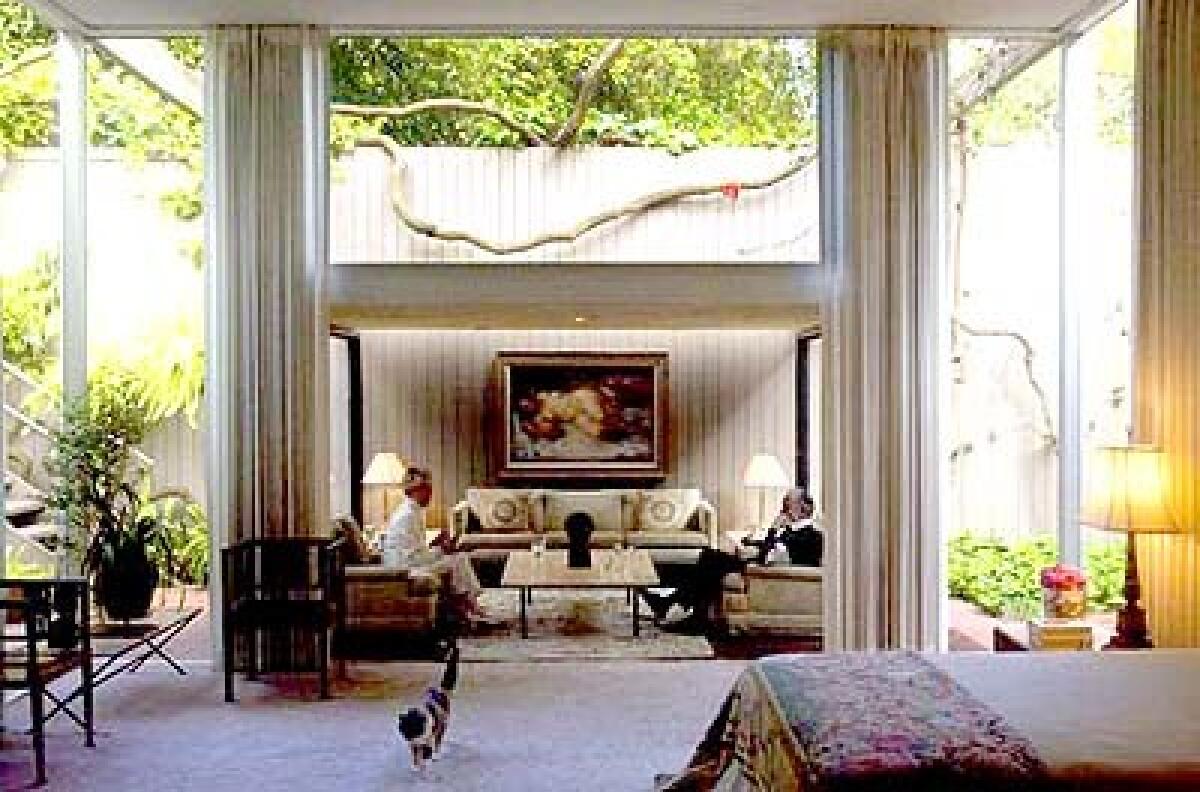

All rooms radiate from the garden room, a space without formal barriers that acts as the central hub of the house. Its 30-foot-tall, skylighted ceilings, trellised cover, creeping vines and white-painted fireplace cast a warm and inviting aura. The room is defined by the interior brick flooring, which integrates with the brick paving in the surrounding gardens and sweeps through the kitchen.

The kitchen is a further testament to the plan’s fluidity. The walnut cabinetry floats above the brick floor, behind a glass wall, allowing natural light to enter. No structural support is visible. Though the dimensions are intimate in scale, floor-to-ceiling glass provides the illusion of a larger space that overlooks an internal courtyard.

Evidence of the Killingsworths’ travels and interests appears throughout: lanterns from Copenhagen flank the front doors, a large Buddha from Thailand sits at the main sliding door, an 800-pound Tibetan sculpture anchors the end of a hallway and an Expressionist painting by Long Beach artist Elsa Warner hangs over the living room sofa (once part of the Case Study House furnishings). The mix of Asian, Danish modern and California artifacts and furnishings blends well with the house.

The gardens remain an essential, if not equal, part of the property. Although lush year round, color dominates in spring. George Tabor azaleas, potted more than 20 years ago, populate the grounds, and massive wisteria creates a huge canopy over a 60-foot-long, rectangular reflecting pool. Forming a natural amphitheater, the courtyard is so much an extension of the living space that in the early 1970s it actually housed a 200-seat theater, used for events staged by the Killingsworths’ sons, Civic Light Opera productions and weddings.

Despite multiple offers and periods of uncertainty during two riots — when upheaval came within several blocks and other neighbors permanently fled the area — the Killingsworths have never considered leaving.

“It is a place where two people can live very comfortably and not feel overwhelmed by unused space,” says Laura. “With so many large homes, people actually only live in a tiny part of them. And the rest of the time you close the doors and clean them once a month. We still live in every bit of it.”