A bouquet for L.A.

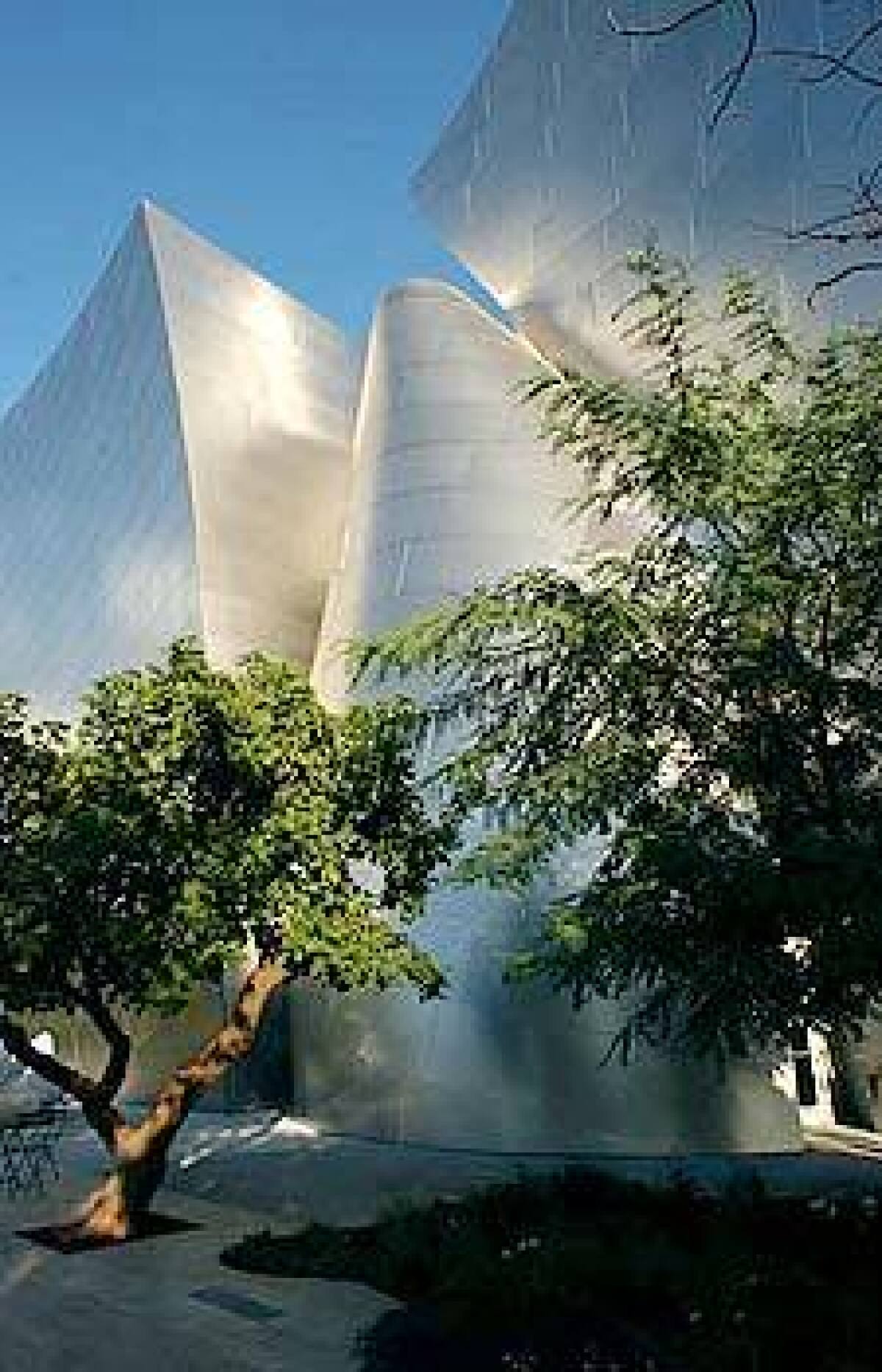

Nothing in the hundreds of photographs celebrating the vaulting steel of the Walt Disney Concert Hall prepares visitors for the romanticism of its gardens. Flowers in landscaping usually are as much an anathema to modernists as rooms with flocked wallpaper. But the more Frank Gehry thought about the garden, the more he wanted flowers, continuous flowers, to bathe the building in color year-round.

The decision is garden as emotion, a tribute from Gehry to Lillian Disney, the woman whose $50-million gift made the hall possible. Disney loved flowers. As Gehry made pilgrimages to her home with early designs for the hall, he was invariably shown to her garden. After these encounters, he began to refer to the building itself as a flower — “a flower for Lillian.” Look at his sketches of it, and, indeed, it looks like a newly opened rose.

As he began thinking about the garden that should surround it, he systematically auditioned and rejected some of the country’s top landscape architects. Eventually, he chose Melinda Taylor, the wife of Craig Webb, Gehry’s partner and his chief architect on the job. Jealous tongues wagged. Taylor was hardly a power landscaper. She had no library grounds, college campuses or public parks to her credit.

But in one way her two-person Silver Lake landscaping firm was uniquely qualified: It specialized in romantic, almost Shakespearean home flower gardens. Most important, she and Gehry already were close; she understood the emotional history behind the project.

“Frank was emphatic that he didn’t want those gardens that people always call ‘architectural’ — modern gardens with pinpoint cypresses and gravel,” Taylor says. She began suggesting trees with interesting foliage, trees with different flowers, trees that put on autumn shows. She’d arrive at his office, and lay out leaves much like an interior decorator would present carpet swatches.

They arrived at a blush of seasonal color. Tabebuias for lavender in springtime, coral trees for summer red, Chinese pistache trees for autumnal oranges, Hong Kong orchid trees and dombeyas for winter pinks and purples.

What looked good in theory now is planted. The result is like an Impressionist painting come to life. Dozens of mature trees shade winding paths. Around their trunks, flowerbeds overflow with grasses, flowers and herbs. Purple salvias ripple in the wind like wheat. The voluptuous profile carries the eye past the hard edges of the boxy neighboring buildings out to the horizon, to the curving ridge of the San Gabriels. In fact, everything about the place, down to the thyme spilling onto pathways, is curvaceous. At the heart of the garden, dense planting gives way to an open circle and a fountain shaped like an unfurling rose. This is the founders’ circle, where by day, office workers will eat lunch, and at night, concertgoers in gowns and tuxes will flow out during intermission.

For every open space in a good garden, there should be a secret one, a private place for intimate exchanges. At Disney, Taylor accomplishes this with an enclave at the western end of the garden, sandwiched between the L.A. Philharmonic offices and concert hall. An old-fashioned Bourbon rose climbs the wall, a Madame de Somebody-or-other, with velvety magenta petals and frank perfume.

The place already seems so natural, so established, that only the occasional seagull sailing by at eye level hints at the artifice behind it. In fact, it is a roof garden, standing 50 feet above ground level over a multistory garage. The mature trees are transplants, set in large beds the size of swimming pools. The illusion of parkland on solid ground is the work of Lawrence Moline, a landscape architect with the very L.A. specialty of designing gardens to grow atop parking lots.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about this Eden in the air is how much closer it is in philosophy and design to a real park than any of the other mow-and-blow gardens lining the mighty institutions along Grand Avenue, or, for that matter, throughout L.A. Most civic gardens are designed less for the tranquillity of visitors than for ease of maintenance of the mow-and-blow team.

By contrast, the Disney park takes gardening back in time to when landscaping was an art of subtly manipulating nature, not an arm of street sweeping. At this new park, visitors can expect the quiet clip of pruning shears as gardeners deadhead the flowers, without the din of mowers.

The decision to put grace over maintenance is pure Taylor. Office workers who lunch in the garden will not need books. Wildlife will be putting on a show. Most of the flowers are good nectar plants. The goldfinches, hummingbirds and swallowtails didn’t wait for the opening. They’ve moved in.

One can only imagine the fights to get Los Angeles County to depart from the regulation five plants normally stuffed in regimental patterns around government buildings, and to accept a plant list of well over 100 specimens. The choice to support her design shows daring and imagination on the part of the state of California and the Philharmonic’s Blue Ribbon Committee, which between them raised the $5 million that it cost to install the garden.

But, finally, the wildness, the sheer abundance of the place reads like nothing so much as an extravagant show of emotion by Gehry. Lillian Disney died in December 1997, but her influence on him permeates the garden. The rose-shaped building and the garden embracing it amount to a deep bow to a lady who loved flowers.

*

The public entrances to the Walt Disney Concert Hall Community Park are at 2nd Street and Grand Avenue and 1st and Hope streets.

Melinda Taylor Garden Design, 2619-A Hyperion Ave., Los Angeles 90027. Phone: (323) 666-9181, e-mail: [email protected].

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.