The not-so-humble garage

- Share via

After 10 days of silent meditation at a Tibetan monastery in India, Sanni Diesner returned home determined to turn her detached two-car garage into something more tranquil than a storage bin. What had been a toolshed and an atelier for her custom wedding dress business became a Zen-like space, a feel-good hub for weekly meditation meetings with friends.

When she went into labor in April, Diesner retreated from her 800-square-foot house to the Marina del Rey garage that became her meditation hall, complete with linen pillows on the floor and the sound of trickling water from a nearby koi pond. A doula, friends and family gathered around a kiddie pool as she delivered her son in the space she says is “loaded with good energy.”

Birthing a baby in a garage? Call it creativity born of a sky-high housing marking that is forcing homeowners to reach beyond a house’s traditional boundaries to make every square foot count. And while few may consider a converted two-car the ultimate delivery room — regardless of how good that energy may be — more and more homeowners are backing their cars out of the garage and using the space to park hobbies, offices and almost anything that will fit in a 20-by-20-foot space.

“People want more breadth of utility for their homes,” says Carole Schiffer, a Coldwell Banker Realtor. “Instead of going to the movies or the gym, they’re converting garages into media rooms and gyms. That’s why we see people putting in wine cellars and all these things that weren’t the hot buttons a few years ago.”

When housing becomes less affordable, garage conversions become a substitute for buying a bigger house, says Ben Bartolotto, research director of the Construction Industry Research Board in Southern California. “We’re seeing a growing percentage toward more expensive conversions for everything from dens to recreation rooms to master bedrooms and gyms,” he adds.

John Stein was looking for a place to do everything from perfecting his ping-pong game to staging theater productions and putting up houseguests when he demolished his dilapidated garage and built a two-story garage and guesthouse in its place. He also was looking for a chance to experiment with design when he hired Richard Aldriedge, a local architect whose work he admired.

“The instructions I gave Richard were just to make a flexible multiuse space over the garage and to make it beautiful,” says Stein, an investment advisor who considers the building “a jewel in the crown on the Venice oceanfront.”

The two-story space toys with angle, composition and materials in a playful way that Stein says “always attracts comments.” Windows capture light and vistas — one wraps around a corner to provide almost dead-on ocean views. There’s the added benefit of having an architecturally significant garage conversion that could enhance the property’s value if Aldriedge’s career enters that pantheon of big-name architects.

Done correctly, a garage conversion doesn’t need a fancy architect’s name attached to increase property value, but it doesn’t hurt, Schiffer says. Any well-executed project done to code that turns the garage into livable space can increase property values by up to 10%, she adds.

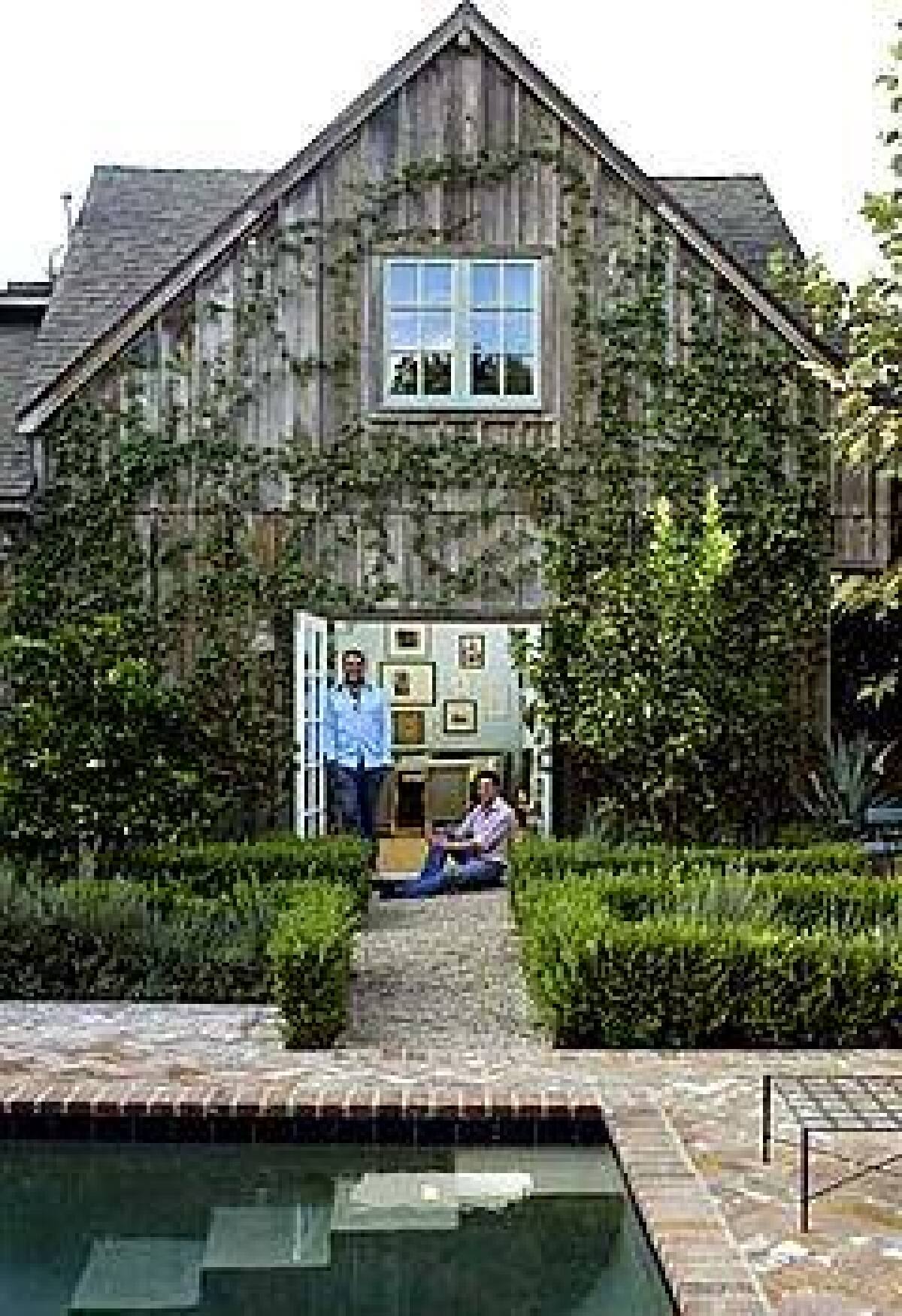

Peter Dunham and Peter Kopelson’s two-story garage may be more of an architectural curiosity than architecturally significant. A previous owner framed two garages — one built in 1925, another added to it in 1939 — in weather-beaten wood siding from an Iowa barn. Forget that it looks like a visiting East Coast relative next to the Mediterranean-style main house. When Dunham and Kopelson first saw it, with holes in the walls and no insulation, it was all they needed to make an offer on the West Hollywood property in 2001.

“This was the selling point,” says Dunham, a British-born interior decorator, sitting in what is now a sisal-floored, antique-filled series of rooms with recessed lighting and French doors that look onto sycamore trees and a recently installed swimming pool. The main house, at 1,600 square feet before they added a master bedroom, wasn’t that small, but it wasn’t big enough for the couple to have a home office, music room and lodgings for frequent guests. Finishing the 1,200 square feet of garage space solved the problem.

Upstairs, Dunham installed offices where he has ample room to work with three assistants and house shelves full of fabric swatches stored in plastic bins for his design business. “I still leave the house to come to work and have a separate phone line for the office,” says Dunham, “but now I don’t have to deal with a commute that had become relentless.”

On the ground floor, the original one-car garage is a cozy guest bedroom with upholstered everything. “It’s a smaller room, so I wanted to go all the way with it,” says Dunham, who used a fabric of his own design on the walls, curtains and pillows. Next to it, in the two-car garage that was added in 1939, Dunham assembled some favorite furniture — an armchair from the ‘30s by English designer Syrie Maugham; a silk velvet Italian settee from Butterfields; a pair of slipper chairs by Valerian Rybar, a jet-setting decorator who became popular in the 1960s — along with drawings, photographs and what he says is the most essential décor for any room: lots of books.

“This is the biggest room in the entire house. It’s both a living room and a piano room,” says Kopelson, who practices Schumann and Chopin on the mahogany grand handed down from his grandparents. “I come in here every morning and play between 5 and 7 a.m.,” says Kopelson, who has a dermatology practice in Beverly Hills. “It’s a meditative act.”

If an unforgiving housing market has made it all but impossible for Angelenos to have music and guest rooms under one roof, the walk out of the house and into the garage may have a hidden benefit. The detached garage seems to offer just that, a detachment from our everyday lives that brings with it the freedom to explore and create. And in this sense, using a garage as a delivery room — at least a figurative one — may not be so uncommon.

Nirvana, the Apple computer and Hewlett-Packard were all born in the garage, which comes as little surprise to Kira Obolensky. “If the house is the ego, the garage is the id of the domestic setting,” she says, likening the garage to the unconscious or primal aspect of a property’s psyche, with the main house serving as the conscious.

The author of “Garage: Reinventing the Place We Park” visited more than 50 converted garages that include two-car garages turned into churches and a private museum for geodes. “There’s something spiritual about entering a space that’s been designated for something else,” she says.

Kevan Jenson was searching for just such an experience when he and his wife, Maria, bought their Venice Beach bungalow. The couple had previously rented a one-room loft, the living arrangement supposedly most conducive to rooming with your muse. But Kevan, a painter, and Maria, a playwright, discovered that two artists in one room, no matter how large, didn’t necessarily permit access to those creative juices. In 1998, they purchased a small bungalow on a large lot in Venice Beach, drawn to it primarily because of a scruffy patch of backyard that abutted the alley.

“When we saw this house, the first thing I thought was, ‘We’ll be able to build a garage/studio here.’ That was the primary reason we bought the house,” Kevan says.

The Jensons enlisted XTEN architects, a local firm known for experimenting with designs and materials, to do the remodel, and Kevan helped plan the garage, which was built from the ground up. Not that he ever planned on parking his car in it. Instead, Kevan, who paints canvas with a combination of paint and smoke, crafted a room with two roll-up doors for cross ventilation, and 20-foot ceilings where he has installed a system of pulleys to help him move a canvas around as he paints. “For some reason they don’t have code for how tall the ceilings can be in the garage,” he says.

They kept the studio far enough away from Maria’s study so Kevan could blast Brahms or Bowie when he wanted, while Maria could convene with the keyboard in relative silence. “A garage is a psychologically different space,” says Kevan, who bounces between the studio and an office inside the house. “It’s not where you live, so it’s a different muse in that room . This arrangement makes it possible to live near my work without it becoming titanic. When you live and work in the same space, you can never get away from it.”

The Jensons joke that, until they get a Ferrari, the garage will continue to be a studio. For Diesner, however, the clutter has slowly crept back. She recently hung a white linen curtain on one side of her garage to conceal baby toys and a changing table. But even before she acquired the surplus of stuff, Diesner had altered the room from a meditation hall into a site for meetings with other mothers and pregnant women, some of whom are former bridal dress clients.

Diesner, who calls the group the “mommy circle,” installed a circular floating bed that hangs from the ceiling and serves as a sofa. “The energy has changed,” she says. “It feels more like a living room now.”

And with each new function the garage takes on, that’s one less reason to leave the house. “We’ve all become a little more insular in how we use our homes,” says Schiffer, the real estate agent. “People feel safe staying in one place. They’ve got that womb thing going on.”

*

Alexandria Abramian-Mott is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].

*

(Begin Text of Infobox)

By the rules

*

In the city of Los Angeles, a basic garage conversion requires two permits: one for the garage and another to build alternate, off-street parking. When garages are turned into livable space, homeowners must provide covered side-by-side parking for as many cars as the garage housed.

Almost any alteration to a garage requires a permit, said David Keim, bureau chief of code enforcement of the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety. That includes something as simple as adding a window or skylight or running more electrical power into the space.

In areas zoned for single-family housing, converted garages cannot have kitchens. If a garage in such a zone is attached to the main house, a full bathroom may be added. If the garage is detached, only a sink and toilet may be put in.

An average carport permit is $350, and garage conversion permits start at around $450.

For more information, visit the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety at https://www.ladbs.org or call (888) LA4-BUILD. In Orange County, call (714) 834-5146, and in Ventura County, call (805) 654-2771.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.