Reinventing itself

Art Astor describes himself as “a city boy at heart.” And so, at 78, he and his wife are returning to Los Angeles — to live downtown. What’s more, Astor, who owns three radio stations in San Diego and another in Ontario, is making the move in high style.

He recently bought a $1.1-million “super-penthouse” in the just-opened Flower Street Lofts, directly across from the Staples Center and a short distance from the USC campus (he’s an alumnus and ardent Trojan fan) and the new Walt Disney Concert Hall (he’s also a classical music buff). He’ll be decorating his 2,700-square-foot space with his prized collection of Art Deco furnishings and objects that evoke both his favorite design era and downtown’s pre-World War II heyday. Astor and his wife, Antonia, plan to spend three or four days a week downtown and split the rest of their time in homes in Tustin Hills and Marin County. After three decades of being away, he says, “I still love L.A.”

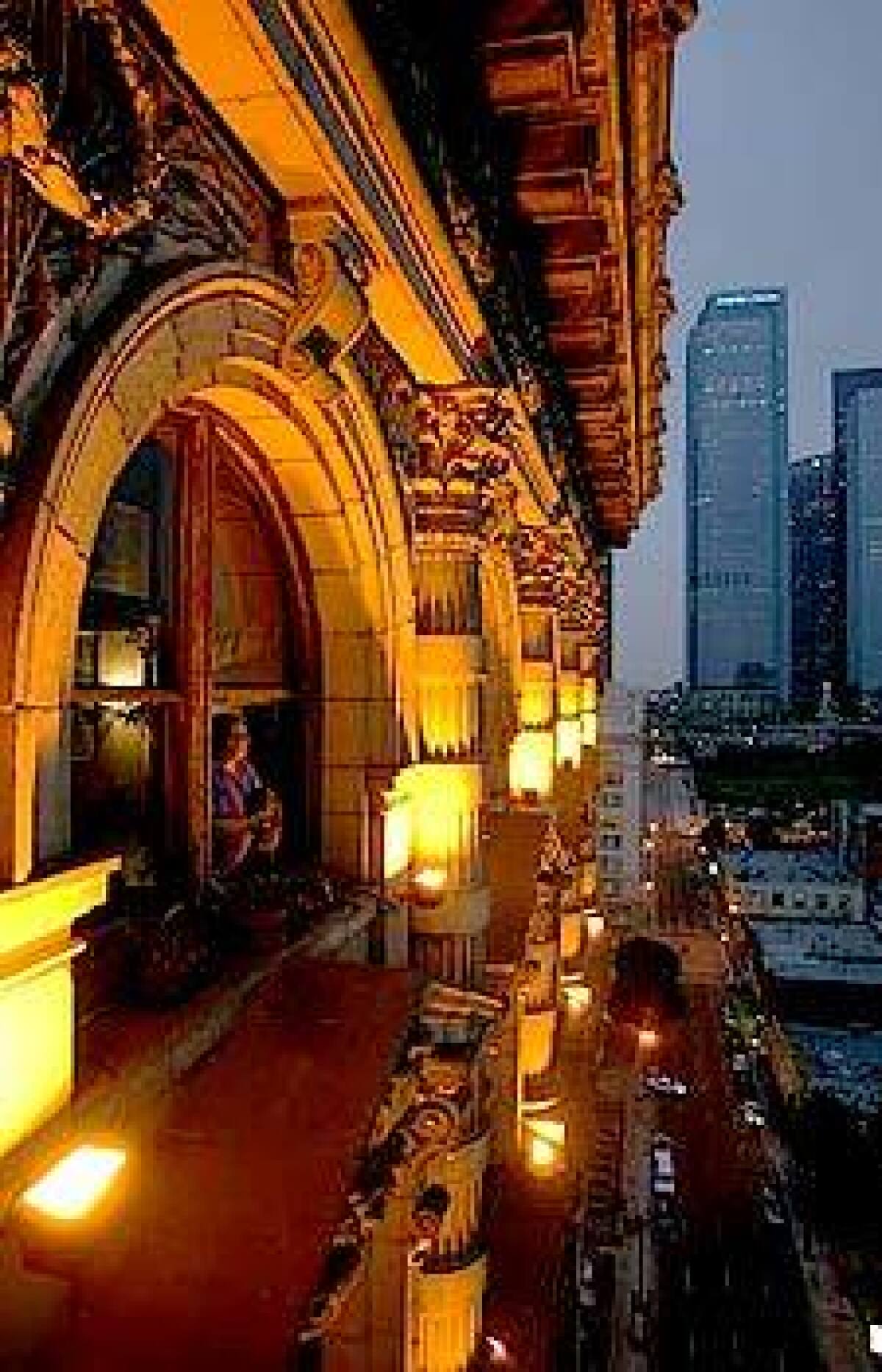

And after years of delays, false starts and greatly exaggerated rumors of its rebirth, downtown shows every sign of being — at long last — on the verge of a major boom. Practically everywhere you turn, it seems, another hulking industrial building or marble-clad edifice is being converted into loft apartments. And, in perhaps the most telling sign of downtown’s arrival as a burgeoning residential community, a 50,000-square-foot Ralphs supermarket is due to open on Flower Street in 2005.

According to figures issued last month by the Downtown Center Business Improvement District, there are 19 new market-rate residential developments under construction downtown and 30 more in various stages of receiving building permits or being reviewed by city officials — big numbers, big money and big expectations to match.

Bank lenders, City Hall bureaucrats and a legion of developers and investors are betting that downtown market-rate housing is reaching critical mass. Some analysts predict that downtown’s total number of market-rate housing units will swell from its present 6,070 to more than twice that number within 10 years. At present, downtown has more affordable than market-rate housing, but the balance is beginning to shift. “The good news about a downtown is it can handle the density. It likes the density,” says Carol Schatz, president of the Central City Assn., a business group.

Eric Owen Moss, director of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, or Sci-Arc, which two years ago moved its campus from Marina del Rey to a former freight depot on downtown’s eastern edge, thinks the center city’s time has arrived for shaping a new identity.

“For a while it was Westwood. Now Westwood is pretty dead on a Saturday. Then it was Melrose, or Old Town Pasadena, or somewhere else,” Moss says. “Los Angeles is downtown, right now. I think it has the potentiality for the most intense and diverse and contradictory energies. You’ve got everything flying in all directions.”

Not so long ago, the pickings were pretty slim for Angelenos living downtown. For many it came down to a choice between a bare-bones loft in a drafty warehouse miles from the nearest dry cleaner or supermarket or else a concrete high-rise atop Bunker Hill.

Today, loft apartments mere paces from skid row are commanding about what you’d pay for a trendy one-bedroom in West Hollywood or Santa Monica. New luxury condos are going for six- and seven-figure sums.

Innovative architects such as Wade Killefer have been hired to transform battered industrial zones and former sweatshops into suave urban showcases. Neo-Hollywood Regency designer Kelly Wearstler, who outfitted the Kor Realty Group’s swanky Viceroy hotel in Santa Monica, Maison 140 in Beverly Hills and Estrella in Palm Springs, was recruited once again by Kor to concoct the cool, minimalist interiors of its new Pegasus apartment complex in the former Mobil Oil headquarters at the corner of Flower and 7th streets (next door to the Standard Hotel, one of the latest bicoastal hipster hangouts in L.A.).

As another indication of downtown’s dramatic makeover, restaurateur Adolfo Sauya and designer-du-jour Dodd Mitchell, the duo behind the ultra-fashionable Zen Grill & Sake Lounge in Westwood, will be giving a serious upgrade to the Bristol Hotel, a 1927 Art Nouveau landmark at 8th and Olive streets. Sauya says the renewed establishment will consist of a hotel with between 80 and 100 rooms, an Asian-themed restaurant, a bar and a nightclub. He expects it to open in mid-2005.

“We can’t go west anymore because we have the ocean,” Sauya says. “We can’t go in the middle [of L.A.] because you can’t buy a piece of dirt for less than $3 million. The only place we can go is east.”

Already, downtown has begun to proliferate into more than half a dozen residential neighborhoods or, in developer-speak, “sub-markets” — Little Tokyo, Old Bank District, Financial Core, Fashion District, Artist District, Civic Center, Toy District, South Park and Chinatown — each with a distinct personality. A wider variety of people are inhabiting an ever-broader cross-section of downtown. And their reasons for doing so are as prismatic as L.A. itself.

Lauren Elliott and Alexander Afanasiev, co-founders of GLO Models talent agency, spotted an ad for Pegasus four months ago. They toured the 322-unit complex and liked what they found: a gleaming postwar edifice designed by acclaimed L.A. architect Welton Beckett, with nickel-plated doorknobs and other original design features still intact, plus a rooftop pool, fitness center and killer upper-story views. Rents ranged between $1,200 a month for a studio up to $6,000 for a two-bedroom penthouse.

The couple took an 11th-floor, two-bedroom unit, which they’ve painted in five different colors and furnished in a futuristic style that Elliott describes as “sort of George Jetson.” They work out of their home, grocery shop at Trader Joe’s in Los Feliz and don’t miss those white-knuckle freeway commutes or mind the lack of amenities. “I still drive to Santa Monica to get my nails and my hair done,” Elliott says, “ because I haven’t found anything that’s comparable.”

She also feels “pretty safe” in her neighborhood, which, like many parts of downtown, is home to a substantial number of street people. Now, Elliott says, when some of the couple’s models “get freaked” at the idea of coming downtown, “we just are like, ‘Grow up!’ ”

Many downtown newcomers are comparison-shopping for amenities like Jacuzzis, gyms, movie screening rooms, 24-7 concierge service and DSL- and satellite TV-enabled units. They’re scoping out aesthetic extras such as cactus gardens and Corinthian-colonnaded facades, as well as in-house conveniences like ground-level cafes, restaurants and small, one-stop grocery stores and delis. “People want a lifestyle,” observes Pegasus co-developer Greg Schem, “and the biggest fear most people have is, ‘If I move downtown, what’s going to happen to my lifestyle?’ ”

Developers say that many of these recent arrivals also want a more “finished” look than the traditional artist’s loft can provide. They’re asking for more drywall, hardwood floors and granite kitchen countertops and fewer exposed pipes and concrete pillars smack in the middle of the living room. Hard-core urbanites, however, may still prefer the blank slate of a traditional loft — cathedral ceilings, exposed brick walls and the like — or else opt for a hybrid loft-apartment that provides a certain level of creature comfort without mimicking the interior of a Newport Beach McMansion.

“You get people who want the historic fabric intact but [also] want the industrial feel,” says Andrew Meieran, who owns the Higgins Building, a 1910 high-rise at the corner of 2nd and Main streets that recently was converted into 135 market-rate loft units. “I’ve seen people building some (new developments) from scratch that are actually more industrial-looking than the ones we’re building, which is always weird.”

Perhaps the most significant amenity many new downtown residents crave is a sense of community more diverse and stimulating than the one they left behind.

“We’ve kind of lived all over, and downtown is totally our favorite,” says Anastasia McAteer, 28, who 2 1/2 years ago took up residence with her husband, John, 27, and two cats in a cozy one-bedroom unit in the Hellman Building in the Old Bank District, after previous stopovers in Burbank, North Hollywood, South Pasadena, West L.A. and Whittier. The Hellman belongs to a trio of historic Beaux Arts buildings whose resurrection by developer Tom Gilmore helped jump-start a listless downtown rental market a few years ago.

Initially, says McAteer, one of the couple’s main goals in moving downtown was to avoid sitting in commuter traffic. She now takes a short bus ride to her fund-raising job at USC, while her husband hops a train to Riverside County where he’s pursuing a doctorate in philosophy at UC Riverside.

But it’s been the less-practical benefits — the intriguing mix of neighbors; the art museums and performance venues; the cosmopolitan vibe at the year-old Pete’s Café & Bar across the street from their building — that have convinced the couple to remain downtown. Even the constant film shoots going on in the alley below their window have grown to be interesting diversions rather than annoyances.

“For us it’s been non-stop activity since we moved,” McAteer says. “It’s kind of like our own little secret society down here. I don’t want too many people to know about it.”

But downtown living is a well-kept secret no longer. And that has some longtime residents troubled.

Richard Montoya, one-third of the comedy-theater troupe Culture Clash, still cherishes such Artist District attractions as the carne asada burritos at Licha’s restaurant, “an old, sweet Mexican place” across the street, and the “Edward Hopper-esque light” that reflects off the bridges and power lines. “I do like the wide-open nature of it,” he says of downtown. “That’s what my brain needs. It’s kind of a mental funhouse.”

But lately, he says, a number of artists have been leaving the area. Some, he believes, have been squeezed out by high rents, while others with young families have moved on to more child-friendly precincts. “Everybody is migrating to Silver Lake and baby packs and play dates,” says Montoya, who has lived in a red brick loft for the last eight years. “I see the migration to Mount Washington and Lincoln Heights. And where there used to be an artist, now there’s four or five kids from USC because they think it’s cool.”

Yet many artists continue to be drawn downtown, even if the rents are steeper and the spaces less cavernous and raw than in the past. Jules Blaine Davis, a painter, performer and poet, came to L.A. five years ago to pursue her muses. Her first address was in Marina del Rey, then a Santa Monica bungalow, followed by a Sherman Oaks apartment and a house on Mulholland Drive.

About a year ago she moved to the then-new 2121 Lofts, at the southern tip of the Artist District. An airy assemblage of brick and metal buildings that were formerly used as a ragman’s warehouse, the 56-unit compound looks out over a vista of tangled freeways and Metro Rail lines. Its shared communal walkways, lined with French lavender and lemon and lime trees, provide a refuge from the urban turmoil. Spanish Moss, rigged up to a concealed sprinkler system, lends a grace note to one interior courtyard, which also contains a small rectangular cactus garden strewn with small green stones.

“I moved here because this is freedom to me,” Davis says. “Down here, you’re in hiding. You can really get things done. I can create. The trains move consistently” — right outside her windows — “and I move with the trains. They go on all night. There’s texture down here. This is reality for me, not the western part of the city.”

Her 1,000-square-foot loft has exposed brick walls, pipes and rafters, along with huge windows and skylights set into the 18-foot ceilings — all the light a painter needs, she says. Rent is $1,400 plus a $128 monthly community fee, not inexpensive for a struggling artist, she says. But she’s been repaid in her increased productivity.

She calls it a neighborly kind of place and “extremely secure. I’ve never felt safer anyplace in L.A.” And though she doesn’t walk outside the gated compound after dark, it’s a quick trip by car to the many good downtown restaurants and not too much farther to Silver Lake, Glendale and Pasadena, where she does marketing and sees films.

“But the truth is, I stay home and work almost all the time. And everything I need is here.” Is it lonely? Not at all, she says. She feels a kinship with her neighbors in the complex, who include artists, photographers, musicians and Web page designers. “Those of us who risk living down here, we’re a tribe.”

If developments like the Pegasus Apartments and Flower Street Lofts herald a sleeker, more up-market trend in downtown living, and 2121 Lofts offers a new spin on the experimental artist’s live-work space, Little Tokyo Lofts combines aspects of all three.

Converted from a 1925 industrial building that belonged to the Westinghouse Corp., the complex combines a thick-walled, broad-shouldered appearance with gentrified extras such as split-level lofts, a pool, Jacuzzi, and a secure multilevel off-street parking structure.

Many of the compound’s 160 units are grouped around a central courtyard, which was formed by removing a section from the building’s core. Two massive concrete pillars have been left to evoke the structure’s blue-collar heritage.

While Little Tokyo Lofts looks inward, it doesn’t turn its back on the surrounding neighborhood. To the north Little Tokyo beckons with dozens of restaurants and such cultural landmarks as the Japanese American National Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Geffen Contemporary. To the south and east lies skid row, while farther east, past Alameda Street, Little Tokyo blurs into the Artist District.

Brock DeSmit, 23, a Sci-Arc graduate student, and his roommate, Jeff Freund, 24, an architect, were among the first tenants to arrive when the building opened in August. After browsing other downtown lofts that were “very large spaces but very unfinished,” they decided that Little Tokyo Lofts offered a happy medium. “Here, you move in and you’re ready to go,” DeSmit says.

Although their own unit is one of the building’s smallest (750 square feet), the roommates maintain an “open-door” policy that effectively extends their living room out into the communal courtyard: Whenever they’re home, they always leave their rear (courtyard-facing) door open, encouraging neighbors to stop in, chat, have a beer. “There’s film students, an art director, musicians, [a guy who] makes music videos, fashion, architecture,” DeSmit says.

But DeSmit, a Detroit native, doesn’t leave his sense of neighborliness at home when he scoots out on his bike to attend classes, run errands or grab a sandwich at a local deli. If he meets someone interesting on the street, he’s liable to strike up a conversation, be it a patrolling cop, a flower merchant or a panhandler.

“I’m an advocate of getting to know everybody as a part of your community,” he says. “I think we’re all earning each other’s respect, which is a good thing.”

Times staff writer Bettijane Levine contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.