Holiday visits with a purpose

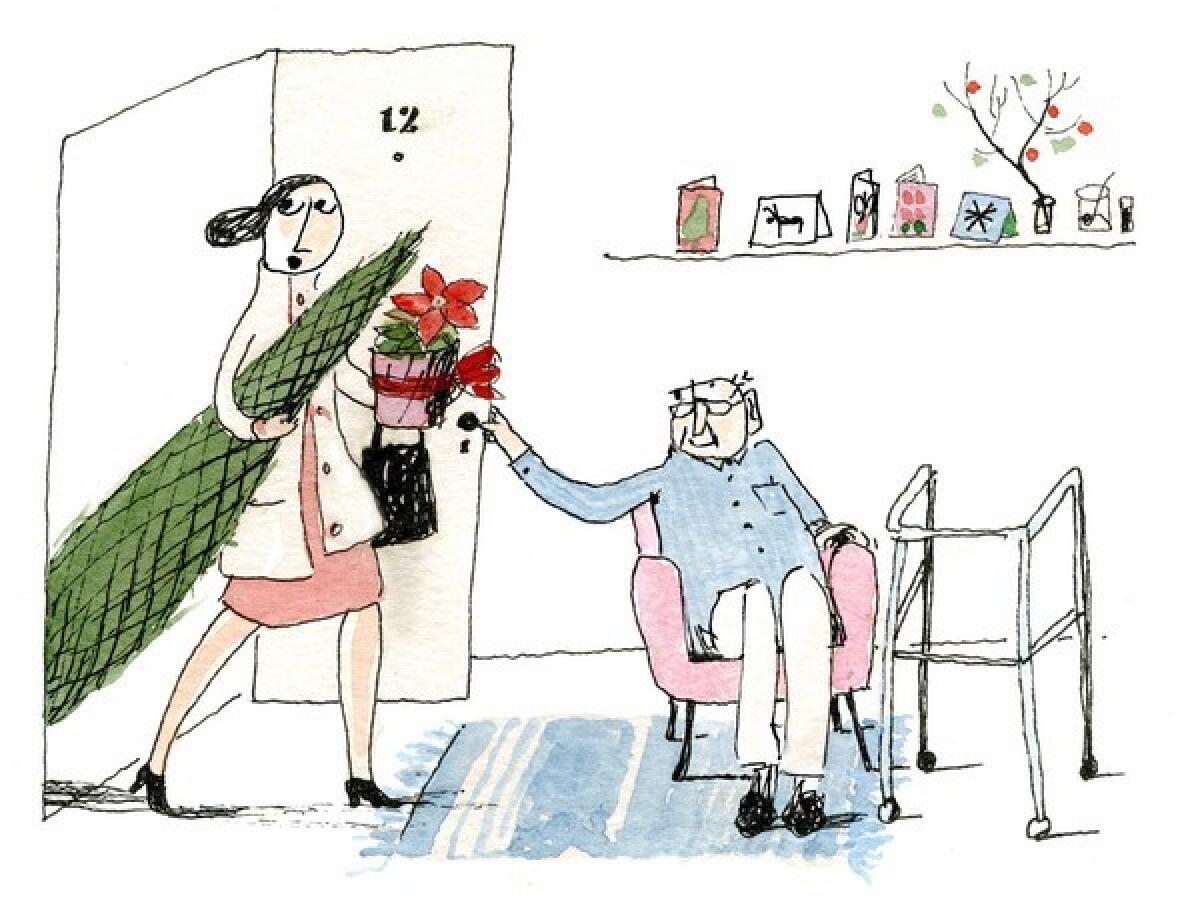

Jane Fickling lives in Dallas, but with the holiday looming, she undertook a cross-country decorating job in Orange County.

Armed with a Christmas tree, a nutcracker, a poinsettia and some other seasonal favorites, Fickling swept into her 95-year-old father’s apartment last week to add a little holiday cheer.

“He’s always so happy when I come,” says Fickling, a Delta Airlines employee. “And I’m happy to be with him. The Christmas decorations were a plus for both of us.” Her dad, Burtis Taylor, lives in Regents Point, a retirement community in Irvine.

Fickling says her visits serve two purposes: She can enjoy her dad’s company and can take stock of his condition.

“It’s so important during those visits to see how everything is going for him and to check on his situation and health.”

Experts couldn’t agree more. Holiday visits, they say, offer a perfect opportunity to assess the needs and health of elderly relatives, whether they’re living independently or in a care facility.

“You should visit with a checklist in your head,” says San Francisco social worker Mary Twomey, who wears two hats -- as a specialist in elder issues and as the daughter of a 78-year-old.

She advises people “to look for red flags: Has your parent lost weight, are they no longer interested in things they once enjoyed, are there any signs of physical abuse?”

And when she visits her own mom on the East Coast, she looks for other, more subtle clues that there may be problems. “Does she have a hard time getting up from a chair or getting around? Are her driving skills still good? Is there a throw rug she might slip on?” she said, then paused. “And I make sure my sisters know not to give her a throw rug; that’s such a hazard.”

Twomey, co-director of the UC Irvine Center of Excellence on Elder Abuse & Neglect, is especially attuned to hazards, both accidental ones and unlawful ones.

It’s estimated that 1 million to 2 million Americans 65 or older have been mistreated by someone they rely on for care, according to the National Aging Resource Center on Elder Abuse. For every case of elder abuse reported to Adult Protective Services, five cases go unreported, Twomey says.

“When you’ve been in this business as long as I have, you develop a suspicious nature,” says Twomey, who suggested another item on your holiday checklist should be to find out if your relative has a new best friend, “someone who might be taking advantage of your parent’s vulnerabilities, either financial or physical.”

What about a good-hearted neighbor who just wants to help?

“There are people like that,” Twomey says, and you need to sit down with the person and get to know them. One of the things you want to find out, said Twomey, is whether money is changing hands, which could indicate a problem.

Another red flag is bruising or other signs of physical abuse, says gerontologist Mario Garrett, chairman of the department of gerontology at San Diego State.

“Are they uncharacteristically covering parts of their body -- wearing a turtleneck or long sleeves, for instance? Do you see evidence of physical trauma, bruises on their arms, legs or neck?”

Garrett also advises adult children to watch for balance problems. Pay attention to how well your parent is walking, and “look for shuffling, especially among men.” One of the most common ways to lose your independence, Garrett says, is to break a hip or leg.

“If there are pets, make sure they do not pose a danger to your relative.” Look for other hazards, such as small pieces of furniture or wires that might cause a fall.

Fickling worries about her dad falling; that’s why her visits to Regents Point always include a close look at his room and the furniture and equipment he uses.

“Is a chair too low? Is his walker too old?” she says. “He won’t complain about something like that. ... But a poorly functioning walker is a serious hazard. That’s the kind of thing you need to see for yourself and replace.”

She also makes an effort to get to know the nursing staff, which is on the front lines when she can’t be. “They’re very important people to me -- and to my dad.”

And if mom or dad is being cared for by a relative -- or by a spouse -- don’t forget the caregiver’s needs during the holiday season.

“If one parent is more frail than the other and the stronger one is a caregiver, make plans to give the caregiver some time off during the visit by taking over for a while,” says Bob Knight, associate dean of the Davis School of Gerontology at USC. “A day or even a few hours can be a big help.”

--

INFOBOX:

A checklist for holiday visits

Things that could indicate a problem, according to Mary Twomey, co-director of the Center of Excellence on Elder Abuse & Neglect:

-- Confusion

-- Depression

-- Inability to handle meal preparation, house cleaning, laundry, bathing or timely bill payment

-- Overusing drugs or drinking too much

-- Frequent falls

-- Undernourishment, dehydration or signs of under-medication

Neglect or abuse is possible if your parent lives with others, or has a caregiver or other helper. Some things to watch for:

-- Caregiver who volunteers to help for little or no pay

-- Recent changes in banking or spending patterns

-- Caregiver isolates the older person from family and friends

-- Caregiver has problems with drugs, alcohol, anger management or emotional instability

-- Caregiver is financially dependent on the older person

-- Parent seems afraid of the caregiver or, alternatively, seems to have a new “best friend”

-- Parent has unexplained bruises or cuts

-- Parent has bed sores (pressure sores from lying in one place too long)

What should you do:

-- If you suspect your parent is at risk, call your local Adult Protective Services or Office on Aging or go to www.centeronelderabuse.org for more information.

-- If your parent seems to be declining, take steps to prevent serious accident and future health complications. Correcting problems can help keep the elderly safely in their homes.

-- Get in touch with responsible neighbors and friends. Give them your address and phone numbers in case of an emergency.

RESOURCES:

Eldercare Locator, (800) 677-1116, can help you determine which local agencies provide service where your parents live.

AARP, (888) 687-2277, provides worksheets on care giving and tips on long-distance issues.

Center of Excellence on Elder Abuse & Neglect, (714) 456-5530, offers services and conducts research, training and advocacy on the issue of elder abuse and neglect.

McClure’s column on caring for and staying connected with aging parents appears monthly. Past installments are in our “It’s All Relative” archive.

Comments: [email protected]