Keeping track of seniors with Alzheimer’s

The e-mail alert shouted its message: “Missing Person with Alzheimer’s. PLEASE HELP.” It was sent to Alzheimer’s Assn. chapters and to law enforcement officials within hours after an Orange County woman disappeared while on a short trip to visit a friend.

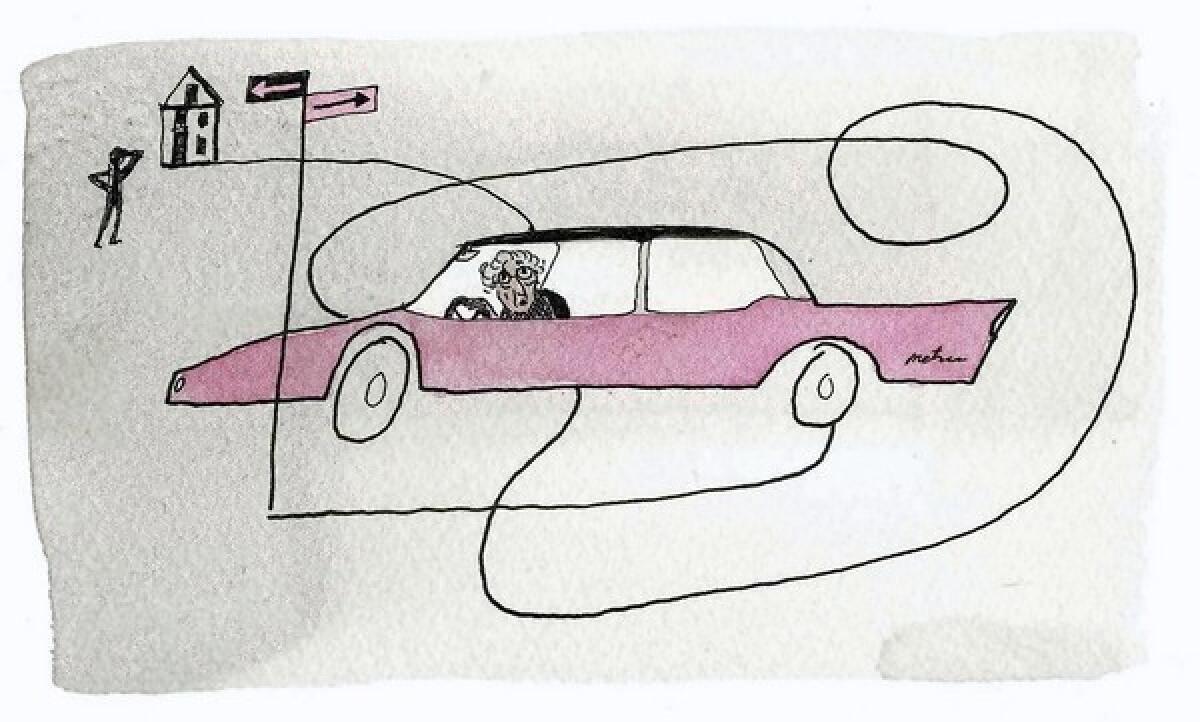

The woman had set out in her car, made a wrong turn and became confused, says her family, who asked that her name not be used to protect her privacy.

During the next two days, she zigzagged her way across two states, making one wrong turn after another, putting ever more miles between herself and her home as she headed east.

“She had a cellphone, but it wasn’t turned on,” says her daughter, Susan. “It was a nightmare.”

The 86-year-old woman had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, but her wrong-way journey shocked her family because until then, she had been able to function normally.

As soon as Susan called the Alzheimer’s Assn. to report that her mother was missing, the organization began sending out alerts asking Good Samaritans who saw the woman to contact MedicAlert + Safe Return, a 24-hour nationwide emergency response service for individuals who wander.

The woman, meanwhile, was still at the wheel, driving south to San Diego, then east to Tucson. Finally, she pulled over to the side of the road and asked an Arizona state trooper how to get to California. He directed her to west Interstate 10. Several hours later she was stopped near Indio by a California Highway Patrol officer, who contacted her family.

“She’s doing fine now,” says Susan. “We took away her car and license, of course.”

That story has a happy ending, but many confused seniors who become lost are never found again. The Alzheimer’s Assn. estimates that 60% of individuals with Alzheimer’s will wander at least once during the progression of the disease. Up to 70% of these individuals wander more than once, and up to several times. One study reported that nearly half of those not found within 24 hours die — usually from dehydration, exposure or injury.

“It’s a scary situation for families who have a relative who wanders,” says Dr. Lisa Gibbs, a UC Irvine geriatrician who directs the school’s Health Assessment Program for Seniors. “It’s easy for the person to get lost and hurt. They’re also very vulnerable to people who might want to take advantage of them.”

Products such as MedicAlert + Safe Return offer families a way to track lost loved ones: It’s one in a burgeoning field, with dozens of devices on the market and new devices and products popping up all the time. Most tracking systems are GPS-based, using the same technology that’s found in car navigation units.

Television commercials for the devices, called family trackers, have become commonplace; they are aimed primarily at parents who worry about their children wandering away during an outing. A small device can be stowed in a child or adult’s pocket, purse or backpack; some are incorporated into wrist bands. They range in price from $100 to about $400, with monitoring costs of up to $80 per month. Most can be purchased online.

At the low end of the technology spectrum is MedicAlert + Safe Return, https://www.medicalert.org/safereturn, an inexpensive program endorsed by the Alzheimer’s Assn.

The product consists of an engraved wristband or dog tag that contains information about the wearer. One call to the number written on the band activates a community support network to help reunite the lost person with their family. When a person is found, a citizen or law enforcement official can call a toll-free 24-hour emergency response number, and the individual’s family or caregivers are contacted, as in the Orange County woman’s case. Costs are $24.95 to set up a plan and an additional $25-a-year fee.

The downside? A Good Samaritan has to see the tag and be able to get close enough to read it. The upside: In the Southland, 160 people have been found because of the Medic Alert + Safe Return tag, according to Jane Dickinson, Alzheimer’s Assn. representative. The product also includes the Alzheimer’s Assn. e-mail alert system, which was triggered when Susan’s mother was reported missing.

Comfort Zone, another product endorsed by the association, is similar to other GPS devices on the market, except that it was designed primarily for people who have dementia. Family members can program it to operate in several ways: In early stages of the disease, it can be used to track a person in a car. In later stages, it can be converted to a bracelet. Alerts are sent to caregivers via computer or text messages. Costs are $199 to $299 to purchase the device, $45 for activation and $45 to $79.99 in monthly monitoring fees.

“What complicates search and rescue for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease is that, unlike a lost child, many will not respond to calls to them, nor will they call out for help,” says educator Andrew Carle. “They often also become quickly frightened and attempt to hide — making locating them more difficult.” Carle, an assistant professor at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., specializes in aging and senior housing issues.

A problem inherent with many of the devices is that they can be removed: A patient with dementia might take off a bracelet or remove a device from his or her pocket, Carle says.

“Paranoia is a manifestation of the disease, so people with AD will often remove anything placed on them with which they are unfamiliar — for example, a ‘clip on’ or other distinct device. For the same reason, they are also adept at getting around locks, alarms or other devices intended to stop them — and, once having done so, are difficult to find.”

Carle’s personal favorite among the monitoring systems on the market is scheduled to be released for retail sale this summer: GPS Shoes. The shoes, which will be sold at https://www.foot.com, (800) 526-2739, will contain a tiny embedded tracking device. Whenever the wearer wanders off more than a pre-set distance, the caregiver will receive an alert by telephone and computer.

The Aetrex Ambulator GPS Shoe will retail for $200 to $300, with monthly tracking available for $22.95 to $39.95, says Patrick Bertagna, chairman of GTX Corp., which builds the tracking device that will be embedded in the shoes.

The device will work anywhere there is cell coverage. If Susan’s mother had been wearing the shoes when she departed on her 500-mile journey, her family might have found her more quickly.

INFO BOX: When to get an Alzheimer’s monitoring system

How do you know whether your dad or mom needs a monitoring system? In California, half a million people suffer from Alzheimer’s or a related form of dementia. Sixty percent of those afflicted will wander or become lost at least once during the progression of the disease. Most of them will wander more than once.

In making a decision, there are some things to watch for in a parent:

Returning later than usual from a regular walk or drive.

Trying to fulfill former obligations, such as going to an old job site.

Being restless, pacing or making repetitive movements.

Inability to locate familiar places, such as the bedroom or bathroom.

Appearing lost in a new or changed environment.

Several organizations offer assistance

The Alzheimer’s Assn., www.alz.org, (800) 272-3900, staffs a 24-hour information hotline. The website offers advice on how to reduce wandering and protect a loved one from getting lost, and how to prepare for an emergency.

The National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center, www.nia.nih.gov, (800), 438-4380, has information on how to recognize the disease, on research into its cure and on coping. And the National Institute on Neurological Disorders, www.ninds.nih.gov/index.htm, (800) 352-9424, has information on clinical trials.

--Rosemary McClure

This column on caring for, and staying connected with, aging family members appears monthly. Comments: [email protected]

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.