Going back to their roots at Nikkei Senior Gardens

Tom Doi harvested a bountiful crop of vegetables last fall: tomatoes, corn, eggplant and green beans. He reaped so much produce from his garden, in fact, that he could share his vine-ripened Big Boy tomatoes with the folks at Nikkei Senior Gardens, a San Fernando Valley assisted-living facility.

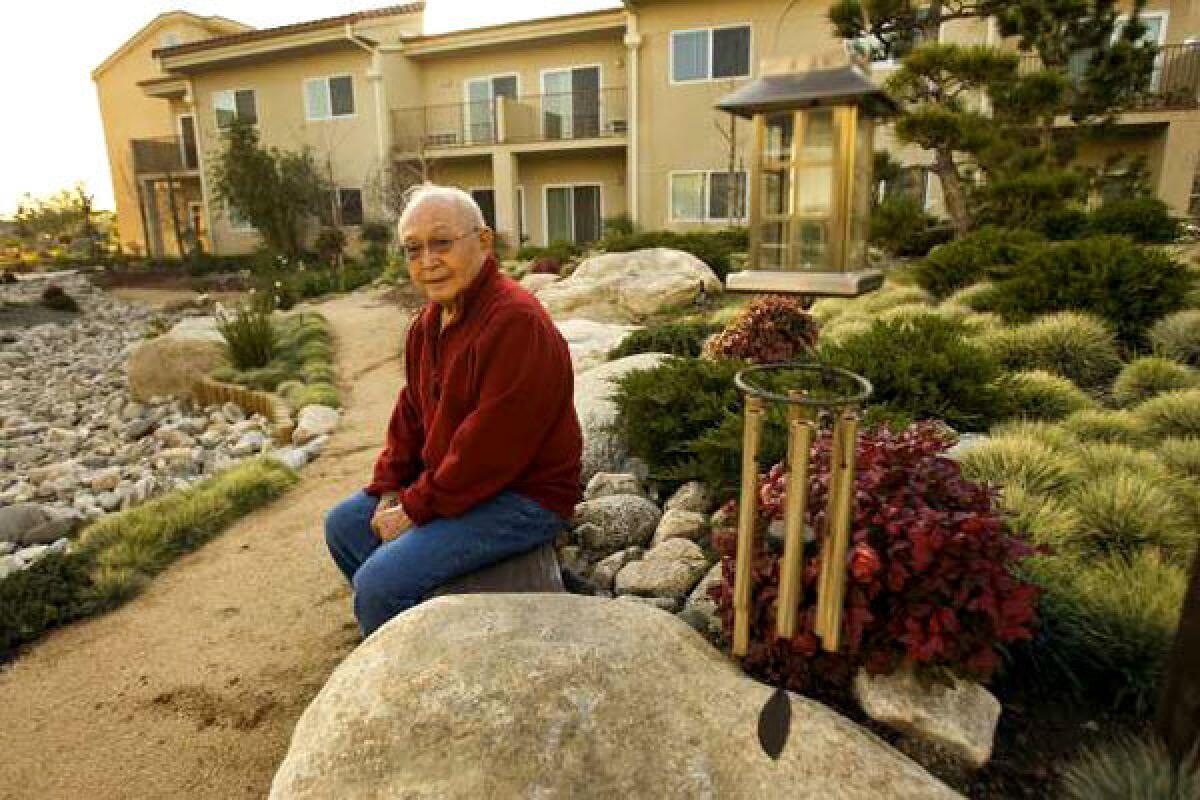

Senior homes such as Nikkei often receive donations from outsiders. In this case, however, the donation came from within: Doi, an energetic 88-year-old, is a resident.

“I’m going back to my roots,” he says. “I’ve always had a yard and a garden to tend. This is the latest one.”

Nikkei Senior Gardens, which opened last year in Arleta, offers retirement housing with a back-to-the-Earth difference: Residents can tend their own garden plots. In addition, the complex includes a mini fruit orchard and an artfully designed Japanese garden. Although the facility is open to residents of all ethnic backgrounds, it was designed to appeal specifically to Japanese American seniors, many of whom enjoy gardening.

Other amenities to make them feel at home: Both Western and Eastern cuisines are served, staff members are multilingual and programming includes courses in Japanese cooking and language. What may seem like a specialized type of senior housing, however, is actually part of a growing trend: niche communities that target specific segments of the population.

“Niche communities represent the future of senior housing because of the sheer size of the baby boomer population,” says educator Andrew Carle, who notes that the nation’s 78 million boomers — the first of whom will turn 65 next year — control 70% of the wealth in the U.S. He predicts the group’s entrance into the retirement housing market will cause massive changes.

“In the future, there will likely be niche communities for nearly every interest group,” says Carle, who directs the assisted-living and senior-housing program at George Mason University in Virginia. Niche housing currently represents only a small segment of senior housing — less than 1%. “But I believe it will grow to as much as a third of the market in the next 30 years,” Carle says.

One reason: As families disperse geographically and aging seniors lose the comfort of care from a blood relative, many essentially look for a second family in people with like backgrounds and interests. Among the niche senior communities currently available:

*For artists and poets: The nation’s first housing complex designed specifically for creative seniors opened five years ago in downtown Burbank. Retirees searching for their inner artist need look no further than the Burbank Senior Artists Colony, where they can find inspiration in the art studio, emote in the theater complex, take writing or poetry classes, sing in the choir or chat up friends in the Hollywood-themed clubhouse.

“It’s the most remarkable place. It’s a family where everyone gets to try all the creative things they ever wanted to try,” spokesman Joseph Caro says. The Colony has been recognized as a model for creative aging by the National Endowment for the Arts.

*For rah-rah university alums: One of the fastest-growing segments of the market is retirement housing on or near college campuses. Residents can take classes, visit the library, hear a concert or catch the big game. Carle says more than 80 university-based communities are open or on the drawing boards, including facilities at Stanford, Notre Dame and Duke. In Los Angeles, Belmont Village of Westwood accommodates UCLA alum and retired faculty and staff; Bruin profs sometimes give lectures at the village.

*For gay and lesbian seniors: Several complexes around the country cater to gay residents. They include affordable housing such as Triangle Square, a 104-unit structure in Hollywood, and upscale developments such as RainbowVision Santa Fe, a 13-acre complex in New Mexico. RainbowVision offers gay and straight retirees a range of housing options, from condos to an assisted-living complex; facilities in Palm Springs and Vancouver, British Columbia, are planned. According to the American Society on Aging, other gay and lesbian retirement communities are under construction or in the planning stages from Washington state to Florida.

*RVers: Happy trails can turn bumpy when RVers become too tired or old to drive but have only a rig to call home. That’s when Continuing Assistance for Retired Escapees steps in. Located at Rainbow’s End RV Park in Livingston, Texas, CARE is a day-care center and assisted-living facility that helps residents who live in their RVs but can no longer travel. They can get three meals a day and a snack, have laundry done and receive transportation to medical appointments. The center’s pitch: “The atmosphere at CARE is more like a RV rally and is nothing like a nursing home.”

Targeting a specific senior market is nothing new: Some of the nation’s oldest senior complexes were founded by and for religious groups: Baptists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Jews.

“There’s always been a component of groups looking out for their own,” says Jon Pynoos, professor of gerontology, policy and planning at USC’s Ethel Percy Andrus Gerontology Center. “We’re seeing more of it now, both ethnically based and affinity-based.”

At Nikkei, the impetus was the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center, which had had the housing development on its drawing boards for a decade.

Toji Hashimoto, a member of the center, had disliked seeing how his relatives fared in a traditional convalescent hospital.

“It was depressing,” he says. “It just seemed like there should be a better way.”

Hashimoto had land, so he went to the board and proposed a senior housing complex. Getting the funding took time, but the result was worth it.

“I wouldn’t mind living here myself,” says Hashimoto, 66. “It’s great for these guys and ladies. They don’t have to cook anymore. They meet new people.”

Some visitors are surprised that Nikkei Senior Gardens was built by and for Japanese Americans, director Allan Slight says.

“They say, ‘I thought the Japanese took care of their own, that they kept their elders at home,’ ” Slight says. “That’s changed dramatically. All the children work. They can’t stay home and take care of their parents.”

Nor do elders want them to, says USC professor Pynoos, who has studied senior housing in Japan.

“Both in the U.S. and in Japan, the elders say, ‘I don’t want to be a burden to my children. I want them to have their own lives.’ ”

When elders opt to move into senior housing, they sometimes find that the choice is more beneficial than either parent or child imagined, he says.

“They meet new people and make new friends,” Pynoos says. “People who were once isolated and depressed become engaged in life again.”

Nikkei Senior Gardens was designed to encourage mixing and mingling. Japanese American designer Toyo Okamoto says the cultural center gave him a free hand “but asked me to keep traditional Japanese architecture in mind and minimize the feeling of walls.” The result is an open and airy design with a central courtyard that features an inviting Japanese garden. An inside solarium beckons residents and guests alike.

The two-story complex has studio and one-bedroom units ranging from $2,800 to $3,600 a month, including three meals a day, 24-hour staff, communal living areas, activities and housekeeping.

“Japanese traditionally enjoy working the soil and planting gardens, which is why the complex has the communal gardens and orchard,” Okamoto says.

The garden plot caught Doi’s eye when he and his wife, Sachie, thought about moving in. As members of the Japanese American Cultural Center, they had watched the complex take shape. Doi, a retired aerospace R&D director, liked the independence of living in his own home, but when Sachie became ill, they took the plunge.

“It’s a golden place,” he says. “You’re among your own people. We have the same background, the same culture; it’s easy to blend in.”

Doi didn’t give his three children a vote in the matter.

“We never asked them what we should do,” he says. “We didn’t want them to make a decision for us. They have their own lives to lead. Besides, if you let your child take charge, you’ve lost your independence.”

Sachie died of cancer in November. Doi thinks about moving out of Nikkei. He’s more active than many of the residents, and he no longer needs the staff assistance. But for now he’s staying put. And planning his spring garden. This year, he thinks he’ll plant some flowers and not as many vegetables.

“Maybe some petunias and roses — something that will make the garden nice and beautiful,” he says. “Something that will last year after year.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.