In Egypt, doctors see strike as their ‘last resort’

CAIRO — The mother, barely past girlhood, was the first to die in Dr. Ahmed Eldin’s care. Her heart would not stir beneath his compressions.

He walked, distraught, out of the intensive care unit that day, past the mother’s child, only a week old, sleeping in the lap of a relative in a dirty corridor of a public hospital, where patients often buy their own syringes, doctors run out of surgical gloves and the pharmacy sometimes lacks medicines that could save those who needlessly slip away.

“She came in for a cesarean section, but the doctor working on her made a stupid mistake and punctured her bladder,” Eldin said. “She stayed in the hospital a week but was given no antibiotics. An infection set in.... By the time they brought her to ICU, we couldn’t save her.”

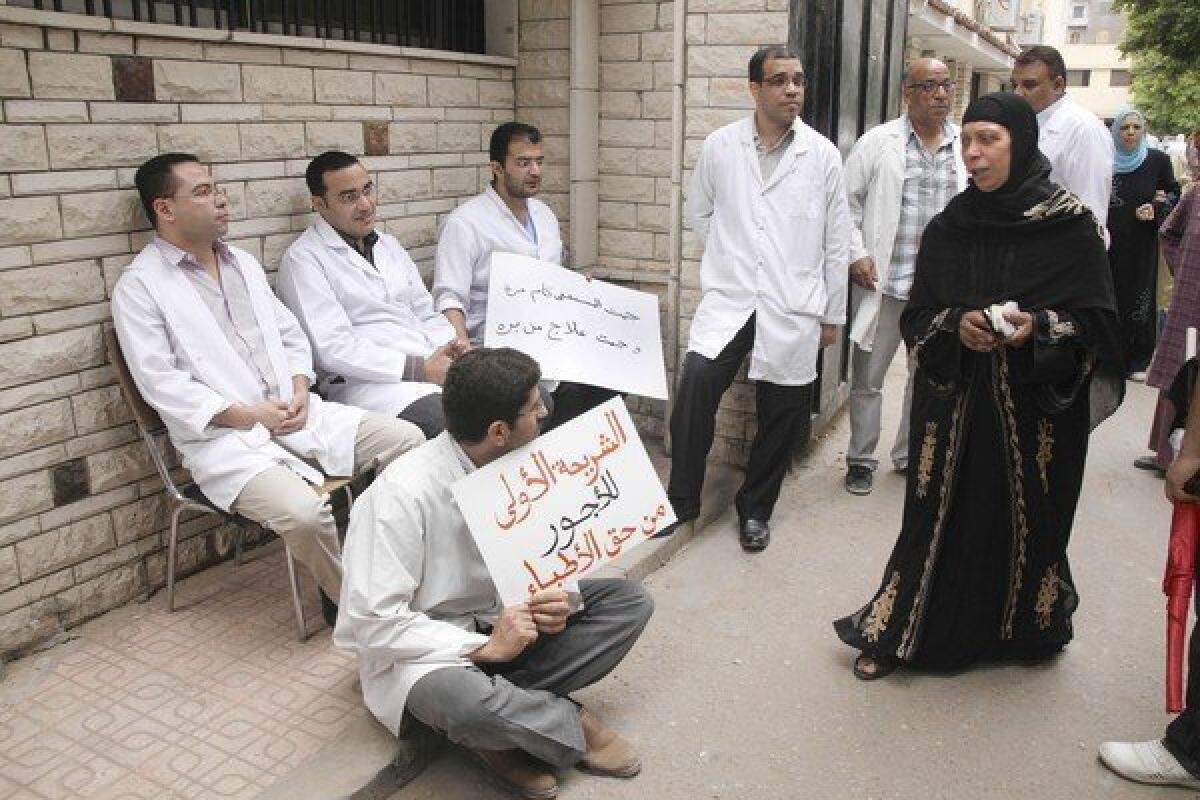

Eldin has many such stories. He told them the other day while traveling from Cairo to a clinic in a village near his home in the Nile Delta. He carried a backpack and led a strike by doctors demanding a larger national healthcare budget, higher wages and tightened security in hospitals that have seen a marked increase in violence, including outraged families attacking medical staff members for not healing their loved ones and gunfights over politics and vendettas.

“I feel like we’re doing triage all the time,” said Eldin, a recent medical school graduate who treated tear-gas injuries and extracted birdshot from protesters during Egypt’s uprising last year. “There are no supplies and no capacity. Hospitals are turning emergency cases away and people end up dying on the way to other hospitals. I thought the country would be doing better by now.”

The state of Egypt’s public healthcare mirrors a nation burdened by economic turmoil, striking workers, widespread poverty, overwhelmed institutions and the sense that little has improved since President Hosni Mubarak was deposed in February 2011. Public services withered under the former autocrat and the country has not recovered from decades of mismanagement.

The government of new Islamist President Mohamed Morsi has promised change but has yet to improve conditions for the lower and middle classes. Disillusionment is high and anger can rise in a flash: Egyptian news media reported in August that irate villagers had held the health minister hostage in a hospital for nearly an hour over illnesses caused by drinking water.

The poor line up for hours in public hospitals, shuffling through hallways with papers and files, pleading to exasperated doctors for an operation, a pill, an X-ray. Physicians such as Eldin, who earns 550 pounds, or $91, a month at a public hospital, often lack the experience necessary for the cases they encounter.

This strike is “our last resort,” said the 25-year-old Eldin. “Look at what the government is spending on police and gas subsidies. The health of Egyptians should be more of a priority. The healthcare budget should be increased from 4.5% of the national budget to 15%.”

It is unclear whether the strike, which involves only public hospitals and does not include emergency rooms, will survive public pressure. Doctors are torn between providing care and advancing their rights; many, despite the partial walkout, still tend to chronic patients and pregnant women.

The Health Ministry said more than 80% of its hospital-run clinics have been affected by the strike. A doctor’s group says 53,000 physicians are honoring picket lines.

“More doctors are going on strike. It seems that someone is heating people up in an effort to incite anger against” the government, said Dr. Ahmed Sedeek, a Health Ministry official who has been negotiating with the doctors. “Their demands are all legitimate, but it is a matter of time.... We inherited a corrupt ministry, how can we change everything in one month?”

The Morsi administration has met with doctors and wants to avert a potential crisis — doctors have threatened as many as 15,000 resignations — amid pervasive social unease. The Muslim Brotherhood’s political party has opened temporary clinics to counter the work stoppage, and some politicians and commentators have suggested that striking doctors are selfish leftists.

Eldin rolled his eyes at such characterizations as he traveled to a clinic in a village near Tanta, a textile and mill city skirted by fields that echo with the chug-chug rhythm of irrigation pumps. He taped a poster to the clinic wall: “Patients’ rights and doctors’ dignity go hand in hand.”

Doctors and nurses complained about a leaky roof, the lack of supplies and having to rely on their own money or village donations to buy or devise makeshift equipment, such as a sterilizing machine.

“The Health Ministry is too lazy to do anything to help us,” said Zaki Morshed, a medic.

The clinic’s pharmacy amounts to a desk and sparse gray metal shelves with scattered pills and empty, or near-empty, boxes. There were no antibiotics. Dr. Zenab Abdellatif said she was concerned that many of the government-manufactured medicines and drugs may lack potency.

“If I met the demands of all the patients, my medicine would run out in three or four days,” she said. “We often have to turn people away and tell them they must buy their own medicine. We don’t want them going away angry but, of course, they are.”

Eldin — never keen on being a doctor, but succumbing to his father’s wishes — grew up in the delta. A trim man with a days-old beard, he knows the pattern of the land, the moods of its people, like Salah Abdel Kader, a farmer with a missing front tooth, who called Eldin over to share a bowl of grapes.

“The clinic has no resources,” said Abdel Kader. “It doesn’t even have kidney dialysis. Even the big hospital down the road doesn’t have syringes. We’re suffering more than before. No gas, no good plumbing, sometimes you can’t find food. The government doesn’t even come to see what we don’t have. I think Morsi speaks into thin air.”

Eldin, aside from his duties at a Cairo public hospital, works at the clinic two days a week. He also moonlights at a private hospital, earning nearly $200 extra a month. Most of his colleagues have similar arrangements. It is the only way to survive.

The government recently granted some labor demands of microbus drivers and flight attendants, but not doctors, who are seeking a salary increase to 3,000 pounds, or slightly more than $490, from 550 pounds for new physicians.

The death of the young mother still bothers Eldin. He remembered glancing at her chart, overlooking her name — it wasn’t important then — amid the fading hiss of the ventilator as he administered CPR.

“I felt helpless,” he said. “It could have been avoided. Her death was a product of ignorance and oppression.... Human life is cheap here.”

Special correspondent Reem Abdellatif contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.