Concussion test moves toward the playing field

- Share via

A two-minute test that can be administered on the sidelines of a sporting event revealed the disruptive effects of brain trauma as reliably as a longer and more unwieldy concussion test used by the U.S. military, according to a study published this week online in the journal Neurology.

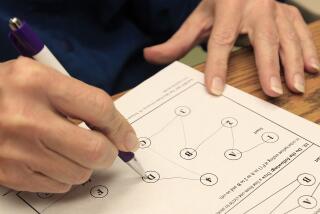

The King-Devick test is designed to identify the presence of disturbed eye movements that come with a blow to the head. Using three cards printed with eight rows of single-digit numbers, a tester asks the test-taker to read the numbers as quickly and accurately as possible. The action gauges not only the test-taker’s balance, attention, language and visual recognition skills, but also his ability to sweep his eyes left to right over a landscape of unevenly spaced characters and keep them on a horizontal plane, then to shift down and do the same, again and again.

Compared with a healthy test-taker’s pregame performance, a post-game difference of just five seconds in the time it took to read all three cards was sufficient to suggest an injury to the brain had taken place.

The study results suggest the King-Devick test “is a strong candidate as a rapid, sidelines screening test for concussion,” the authors write. It could be particularly helpful in identifying athletes who should be removed from play and assessed for possible concussion in such contact sports as football, soccer, hockey, mixed-martial arts fighting and boxing, the authors said.

That test comes as calls mount for tighter rules to protect young athletes from concussion and its sometimes persistent effects. Last November, the nation’s neurologists issued recommendations that any athlete suspected of having sustained a concussion be removed immediately from play and not returned until evaluated and cleared for play by a physician trained in the assessment of concussion.

At the same time, the neurologists acknowledged that, with parent and volunteer coaches on the sidelines of many games, the decision to bench a potentially injured athlete is left in inexpert hands. Even where there is a strong desire to protect youthful players, there are few tools available to help identify which kids need to be sent to the bench, they noted. Though the military’s screening tool is considered quite reliable, it’s too long and complex to be a practical guide on the sidelines.

Among the paper’s 12 authors, one has applied for a patent in connection with the King-Devick test, which is already being marketed to individuals, families and teams on the Internet. They are being tested in a large prospective study of athletes at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Neurology study describes a trial in which 39 subjects -- 27 young boxers and 12 mixed-martial arts fighters -- were tested before and after sporting events in which they were at risk of concussion. Each boxer took the test twice before the the event; all the MMA fighters took it the day before an MMA event, at their weigh-in. After the sparring session, all seven boxers who had had overt blows to the head -- whether or not they lost consciousness -- were administered the military’s screening test for concussion, the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (or MACE), which takes 15 to 20 minutes to administer but is considered one of the most reliable tests for concussion. All of the MMA fighters took the MACE test afterward, whether or not they had received blows to the head.

The eight athletes who had received blows to the head all performed significantly worse on the King-Devick test (it took longer for them to read the numbers), and those who had lost consciousness performed most poorly, the authors reported. Those whose scores worsened the most were those who had fared most poorly in the military’s concussion assessment.