Waiting for a liver transplant, she tries to reclaim the rhythm of her life

- Share via

WHEN you’re lying in bed and can’t keep food down, muscle metabolizes first.

Dr. Zhaoping Li, my UCLA clinical nutritionist, says the rate is two to three pounds of muscle wasted for every pound of fat. Bug-eyed and big-bellied with fluid after four months’ hospitalization for liver failure, I had legs and arms like matchsticks. I could walk no farther than one block. Me, the lifelong athlete, former aerobics instructor and dancer -- now wait-listed for a transplant.

My diagnosis seemed unbelievable: An ultra-rare disease, Budd-Chiari Syndrome.

Two years later, not yet dead, not yet given a liver transplant, I’m told by Li that I must increase my muscle mass. If I am hospitalized again, I’ll lose even more muscle and might not survive.

And so I find myself one foggy Tuesday morning at a low-impact aerobics class. The instructor is world-renowned, a fitness leader. A volley of words echoes around the studio: “Oh, isn’t her body amazing?” and “Look at how toned she is.” I squish down memories of days when I looked that toned.

My shoes are flexible, lightweight, cushioned in the right places and ready for rebound, thanks to advanced cantilevered technology. My full-length pants and long-sleeved pullover, neither stylish nor new, are oppressively hot. I don’t want anyone to see the purple bruises on my legs and arms, will not bare my scarified, herniated belly and kangaroo-mama pouch.

No one in the class knows me, and though my mind tells me I should feel grateful to be alive, I feel ridiculous and vain.

I approach the instructor with a smile, saying, “I might need to modify some of the moves.” She looks at me blankly and turns toward the mirror, starting the warm-up: Shoulders roll, backs curl and straighten, knees bend deeply.

My own thighs burn. Five minutes in, I gasp. My heart rate exceeds 200 beats per minute, well over the “training” zone for my 45-year-old body. I put a smile on my face that I do not feel -- some say if you smile you actually make yourself feel happy -- and keep moving my feet, dropping my arms to take the intensity down and relieve my heart.

The instructor picks up the pace, moving into choreography without cuing ahead. The canned music grates.

My head throbs from pills I took the night before, and my face flushes crimson, as veins and capillaries struggle to open, impeded by blood clots in my liver. To keep myself from the creeping onset of a dizzy spell, I slow down, count the beats and cue to myself.

For 16 counts, we lead with the left foot, until she abruptly jerks to the right. I expect a repeat of the four-count, but she returns to the original 16. The instructor’s lack of rhythm disrupts my tenuous kinesthetic control. It feels as if I’m descending stairs quickly, hands-free, eyes closed.

Several coordinated students falter. A woman in red shrugs.

“You missed it,” the instructor says, turning around long enough to give an odd, half-smile.

I try not to get in anyone’s way, mimicking her jerky movements, but lessening their intensity. She stops mid-pivot, looks at me and frowns, saying, “Pull your right knee up.”

I glare, nauseous.

“Geez,” she says, shaking her head as if I were a disobedient child.

The woman in red maneuvers to my side and whispers, “She has no rhythm.” I giggle, and she adds, “You can’t take it personally,” then breaks away to her spot in the row ahead of me.

“I don’t,” I say, even though I do.

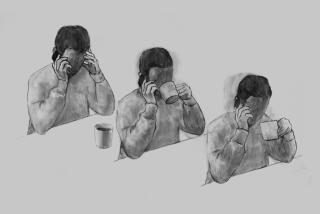

For 15 more minutes, I struggle to keep up, but the instructor’s rigid ego and mediocre technique are as hard to bear as burning, slow-drip IV meds or interns digging into arteries. My resolve slips. I weave my way off the studio floor, fall into a nearby armchair and cry.

“Tomorrow,” I tell myself, “You’ll try again.”

Linda Alcorace is a wait-listed liver transplant patient, adjunct instructor of English at Santa Monica College and a former employee of Copley Press. She lives in West Hollywood and is working on a memoir.