Hope for Roquefort fans

- Share via

On a recent afternoon, customers of the Los Angeles gourmet shop Joan’s on Third were greeted with a one-pound wedge of L’Aigle Noir Roquefort, its blue-speckled innards showcased on a glass pedestal amid tidy piles of other artisan cheeses. Hanging above the display, a black slate declared in white-chalk scrawl: “Get it while you can!!!”

The fate of the French-produced blue cheese may depend on whether the U.S. and European Union settle a trade dispute over hormone-treated beef. On April 23, a 300% U.S. tariff on Roquefort is scheduled to go into effect, sharply raising prices and thwarting imports.

Days before President Bush left office in January, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative said it would triple the tax on Roquefort, originally levied by the Clinton administration at 100% in 1999 to retaliate against a long-standing European Union ban on hormone-treated American beef.

“It’s such a blatant, petty move on the White House’s part,” said Chester Hastings, manager of Joan’s on Third. “It reeks of ‘freedom fries.’ ”

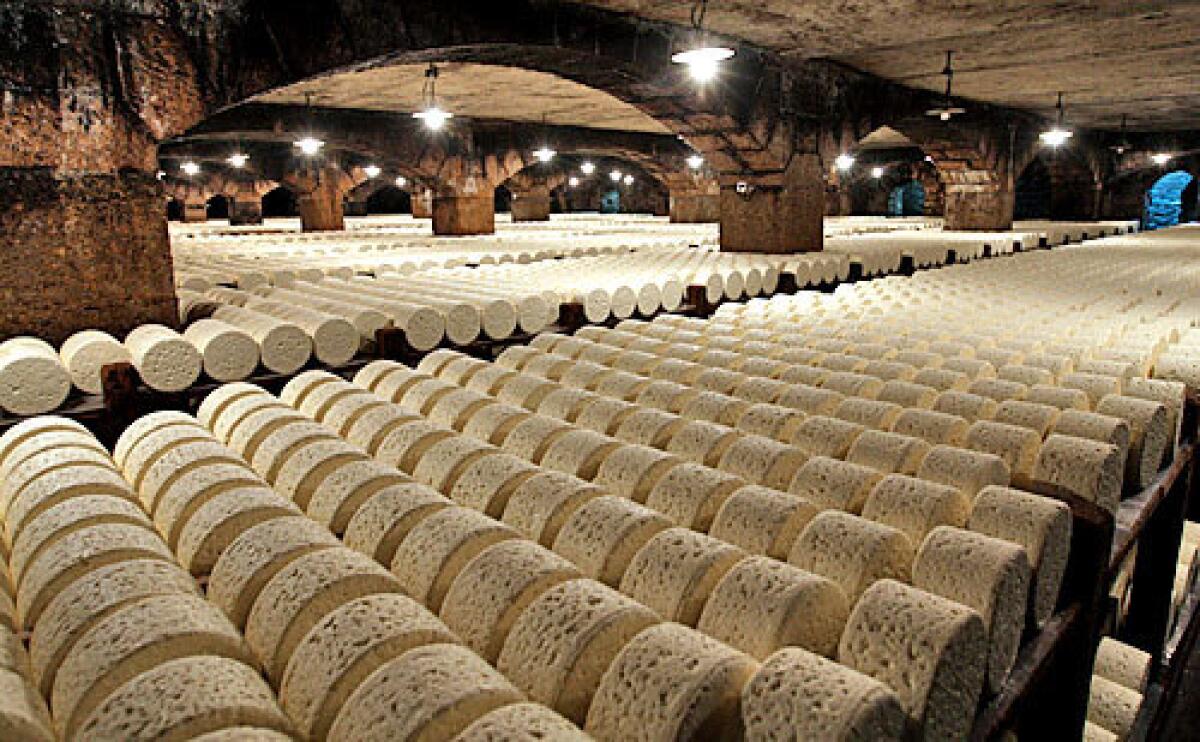

The L’Aigle Noir Roquefort at Joan’s on Third retails for a hefty $71 a pound. Once the tariff goes into effect and current supplies run out, L’Aigle, which is inoculated with several strains of the penicillium roqueforti naturally found in the Combalou caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, could easily cost more than $100 a pound.

“There’s not a day that goes by where people don’t ask me, ‘What are you going to do about the Roquefort problem?,’ ” said Alex Brown, general manager of Gourmet Imports, which supplies a selection of 400 to 700 cheeses to many retail shops and restaurants, including Campanile, Providence and Craft in Los Angeles. “I’ve just been hoping [the levy] would be taken to a happy place where it’s put on hold.”

Tariff delayed

The tax had been set for March 23, but last week the federal trade agency delayed the action for a month to foster a resolution over the beef dispute. “The Obama administration is continuing the long-standing U.S. policy of trying to reach a negotiated settlement that offers real benefits to the U.S. beef industry,” said agency spokeswoman Nefeterius McPherson.

Despite Roquefort’s renown, exports of the AOC-labeled (a French certificate guaranteeing “protected designation of origin”) fromage to the U.S. are relatively low. Of the 44 million pounds of cheese France exports to the U.S. annually, 630,000 are Roquefort. But for Brown, it’s not just any old cheese.

“I’ve tasted hundreds and hundreds of cheeses,” he said. “I’ve never had a sheep’s milk blue cheese that is as good as Roquefort.”

In 1999, the World Trade Organization authorized the U.S. to take EU-targeted trade actions worth $116.8 million annually, equal to the trade loss from the ban on American beef. When the U.S. trade office made revisions this year to the list of taxed EU items, which includes meats, chocolate and mineral water, only Roquefort’s tariff was tripled. A U.S. trade official says the cheese was singled out because of its persistent sales despite the 1999 levy.

Dan Rotenberg, counselor for agricultural affairs in the Delegation of the European Commission to the USA, said: “This delay shows that reasonable progress has been made. On the other hand, it also shows that there was not yet an agreement.”

The secretary general of the Confederation of Roquefort, Marie-Elisabeth Verdaguer, said the tariff is “groundless.” (The confederation represents a union of 4,500 sheep farmers and seven Roquefort manufacturers.) “Since 1999, we’ve been held hostage in this conflict,” she added.

Meanwhile, U.S. cheese lovers would likely pay the price: If Roquefort sells in France for $10 a kilo, a U.S. importer would pay that amount plus a $30 tariff, not to mention brokerage fees and shipping costs. Even more, beginning April 1, when the Roquefort confederation drops its 10-year subsidy, an additional 4.57 euros ($5.93) per kilo might go on the bill. Local purveyors, including Say Cheese in Silver Lake and the Cheese Store of Beverly Hills, have begun stockpiling to avoid price increases through September.

Ihsan Gurdal, co-owner of Formaggio Kitchen in Cambridge, Mass., and Formaggio Essex market in New York City, has also put in extra orders and forecasts that retail customers will start seeing Roquefort price hikes as early as May. “Nobody is going to buy Roquefort,” he says. “In this economy especially, [selling] anything over $20 a pound has become challenging.”

Limited availability

Other retailers, including Whole Foods Market, have said that Roquefort will be available in limited quantities or will have to be special-ordered. Although Roquefort is known to age well, its refrigerated shelf life is about three to six months, and it may not be worth the financial risk in case it doesn’t move. “Even if I did feel comfortable buying a ton and sitting on it, I don’t have the money to do it,” says Brown of family-owned Gourmet Imports.

Currently, Trader Joe’s sells Société Roquefort at a bargain $13.99 a pound. However, a spokeswoman said the grocery chain will be discontinuing it.

Meanwhile, Roquefort producer Gabriel Coulet has offered importers an alternative. Coulet plans to produce Brebis Blue -- tentatively based on Roquefort recipes and, like the original, made with raw sheep’s milk -- for U.S. customers. Without a Roquefort label, the duties plummet to 15%. “I have a feeling that we are going to order the [Brebis Blue],” says Formaggio Kitchen’s Gurdal.

Denis Cottin, director of affinage at Artisanal Premium Cheese in New York, has yet to field such an offer. But he says he won’t go for it.

“Some may say, ‘I like Champagne, but I change for sparkling wine’ and go for $15 Chandon of California. ‘I still have bubbles and a good party.’ But some people would say, ‘No, I will continue to buy Champagne.’ That is the same thing for Roquefort.”

He suggests that consumers express their concern to lawmakers. “If your senator or congressman is receiving 200 letters, he will suddenly be very sensitive to Roquefort,” he says.

One congressman, Rep. James L. Oberstar (D-Minn.), sent a letter to President Obama last month, criticizing the trade action.

“Though I am a supporter of ‘buy American,’ it is for unfairly subsidized foreign products when they are identical or comparable to ours,” Oberstar wrote. “Roquefort cheese is not in this category.”

Oberstar says he has not received a response.

The lack of public protest has surprised chef Conny Andersson of AK Restaurant in Venice. “It’s like no other cheese,” says Andersson, who has had a mesclun salad with Arkansas black apples and Papillon Black Label Roquefort on his menu since he opened in December, a month before the new levy was announced. “There should be some kind of chef movement against it.” He plans to continue serving it until his current $17-a-pound wholesale price goes up.

In the meantime, the Confederation of Roquefort plans to release a television ad promoting the cheese within France, as well as develop other foreign markets. The U.S. is the No. 3 importer of Roquefort behind Spain and Germany.

It may not be all bad news. Hastings of Joan’s on Third sees an opportunity for artisanal blue-cheese makers that have blossomed stateside in the last 10 years. “I would never stoop to think any of us could re-create the flavor of a Jacques Carles [the producer of L’Aigle Noir], but if times are hard and we’re not able to afford it, we’ll dig deep and make it our own way,” he says. “Rogue River Blue from Oregon is an incredible blue [albeit from cow’s milk].

“It’s the classic great American know-how. We can’t have it right now, but it doesn’t mean we’ll go without.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.