The inside scoop on making gelato

- Share via

Reporting from Bologna, Italy -- — Leave it to Italy -- a country where food and tradition go hand in hand -- to be home to the first university dedicated to the art of making gelato. In fact, the Carpigiani Gelato University, located outside Bologna, is doing its all to ensure that the future of ice cream’s closest relative, gelato, will continue to be that of a fresh product made from all-natural ingredients for local consumption.

Carpigiani, which has sold gelato-making equipment since 1945, started teaching the classes in 2003. Its courses have attracted students from more than 100 countries, many of whom returned home to open their own Italian-style gelateria. Carpigiani graduates hail from the expected places such as Italy, the United Kingdom, France and the United States, but also the unexpected, such as Sudan, India, Iraq and Iran. Enrollment from Asia and South America is booming, while the Middle East —Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Dubai — provides a steady flow of pupils.

Classes are held at the sanitary-looking white Carpigiani headquarters along Via Emilia, an industrial byway constructed by the ancient Romans. One recent crop of students — 41 in all — resembled a United Nations conference. Japanese, Brazilian, Indian, German, American, Polish, Nigerian, Mexican, Belgian, Turkish and Tanzanian students were focused on the impassioned words of program developer Luciano Ferrari and gelato maker Alessandro Racca, who teach the art and science behind their trade.

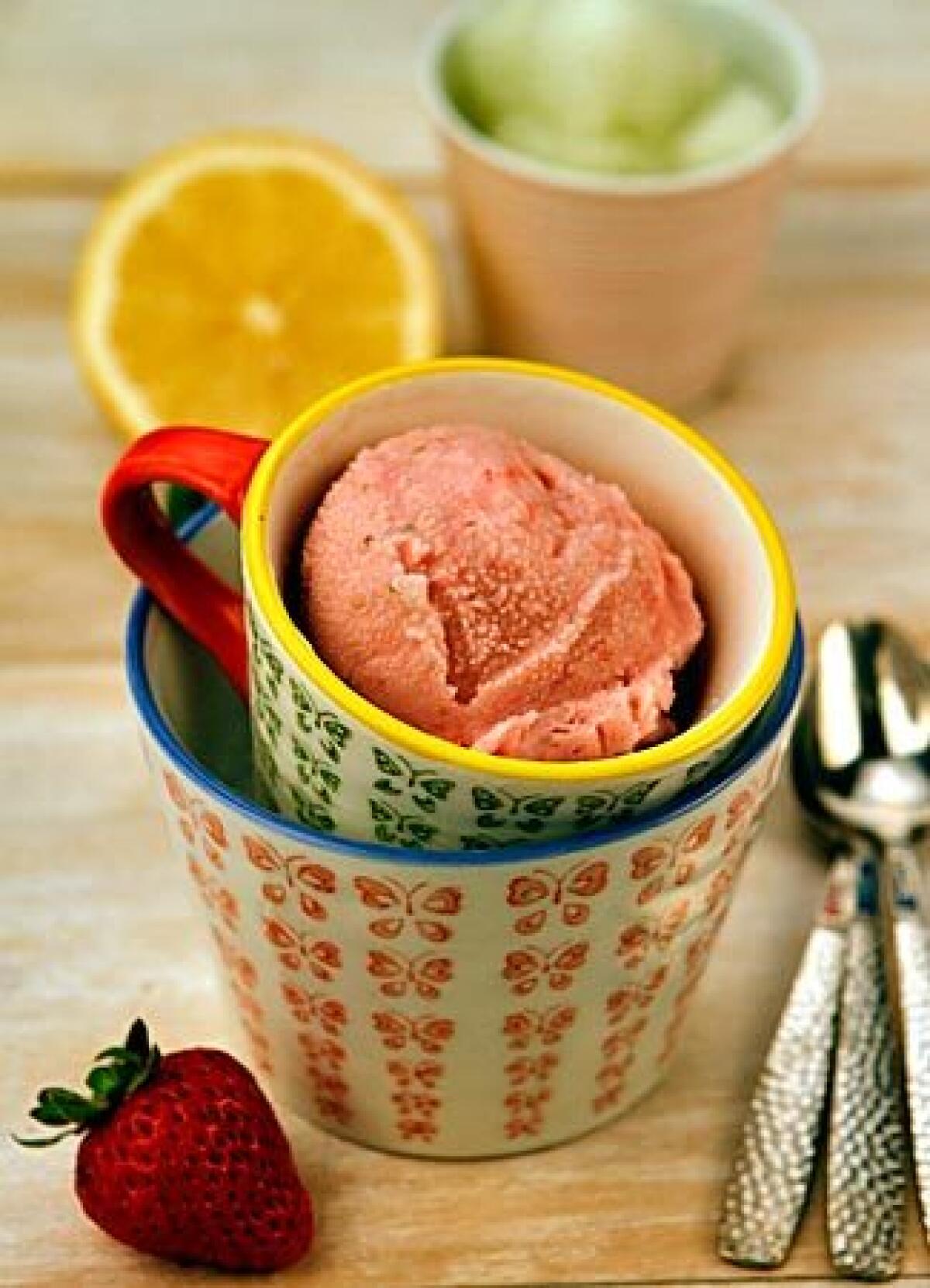

Recipes: Chocolate gelato, Lemon gelato, parmesan gelato, strawberry gelato (milk-based) and strawberry gelato (water-based). If you make any of the L.A. Times Test Kitchen’s recipes in your own home, we want photographic proof. Click here for details.

The instructors start by explaining the difference between gelato and ice cream. Gelato has less fat than ice cream (3% to 9% to ice cream’s 10% to 16%), contains less air (gelato has 35% to 40% air, ice cream as much as 90%) and is served at a higher temperature. As a consequence, “the intensity of the flavor of gelato hits your palate faster than the flavor intensity of ice cream,” Ferrari says.

Racca simplifies: “Ice cream is very hard and not too creamy. Gelato is creamy and not hard.”

Though most ice creams require hardening after freezing, gelato can be eaten when first squeezed out of the grate of the mantecatore — the freezing machine used for commercial gelato making.

“The best gelato is the one that comes directly out of the machine, so gelato is always eaten fresh,” Racca says.

The finished product is visibly different from ice cream. “Gelato has a matte surface,” Ferrari says. “You don’t want it to be shiny, as this would reflect on an amount of water that still needs to be frozen. Overall it looks dry. … A good structure is one that holds the peak like a meringue. Texture-wise, it has got to look smooth, like a silk fabric.”

Those who have traveled to Italy are familiar with the numerous gelaterie that tempt passersby with curvaceous mounds of multicolored gelati. Normally, gelato, which is chemical-free, is produced and replenished throughout the day. Since it is made with fresh ingredients, it can’t really sit around in the freezer. To be at its best, gelato should be eaten at least within two days of being made.

Gelato “is a balance between water and other ingredients like sugars, fats, milk solids and fruit,” Racca says. “The aim of Italian gelato is that it is low fat, low sugar and low calorie. It is possible to make strawberry gelato with only strawberries, sugar and water — no more.”

In fact, such a gelato was created during the class. Though sherbet and sorbet can have a grainy texture and tart taste, the gelato alla fragola was so creamy you’d swear it contained milk — but it didn’t, just as it didn’t leave a sugary aftertaste on the tongue. Similarly, a milk-based strawberry gelato, or fior di fragola, had the same strawberry burst but an even creamier back flavor.

A balanced cream-based gelato begins with a base. The simplest is a white base, which essentially is made of sugar and cream. Cocoa or egg yolks can be added, depending on the recipe. Commercial gelatos usually use a stabilizer such as guar gum, which ensures that fats stick together in sub-zero temperatures. That’s not necessary for homemade gelatos.

Another difference between homemade and commercial gelatos is the type of sugar added. At home, granulated sugar works just fine, but at the gelateria, they’ll use a mixture of granulated sugar, dextrose and sucrose, a combination that gives less sweetness to the gelato and keeps it softer and easier to spread.

Once the base is mixed, it can be heated to 185 degrees, which Racca refers to as “pasteurization” — for sanitation and to improve the flavor. Then it is chilled in a standard refrigerator for three hours to two days. Racca refers to the time after pasteurization and before freezing as the “aging process,” which serves to enhance flavor.

When enough time has passed, you simply combine the base with the flavor, such as strawberries, mix again with a blender and then freeze. For home preparation, Racca recommends keeping the freezing simple. Hand-whipping the mix in an aluminum bowl set over a mix of salt and ice produces satisfying results. Once the gelato starts to get creamy, you can put it in your freezer to finish it. Ideally, gelato should be kept at 5 degrees.

How do you know if you have a “good” gelato? You don’t “chew” it. It’s softer than ice cream, but not so soft that it melts. Ferrari calls it an in-between state.

Once you’ve mastered the gelato basics, you can get creative. Ferrari mentioned a cardamom-coffee mixture he tasted in India and a trout sorbet served in Japan (intended as a palate cleanser between courses).

Even in Italy, there are some unusual flavors. A client from the Piedmont region asked for a line of gelatos based on cheese. Among the possibilities, a blue-cheese-honey-caramelized-walnut gelato, which even Ferrara found bizarre. “But it was surprisingly good,” he says.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.