Lost and Found. And Lost Again?

- Share via

Los Angeles, 1967 — Nadia Tupica was driving down the freeway in her cream-colored convertible Thunderbird when she spotted what looked like a small body. She pulled over to investigate.

As Tupica approached the object on the ground, she must have been alarmed that someone was hurt—or worse. The searing August heat pulsed against her skin. The wall of sound from cars racing by filled her ears. But as Tupica got closer, she realized that what she had seen was not a body but an oblong case protected by a canvas cover lying among bits of trash, ice plants and poisonous oleander growing along the freeway corridor.

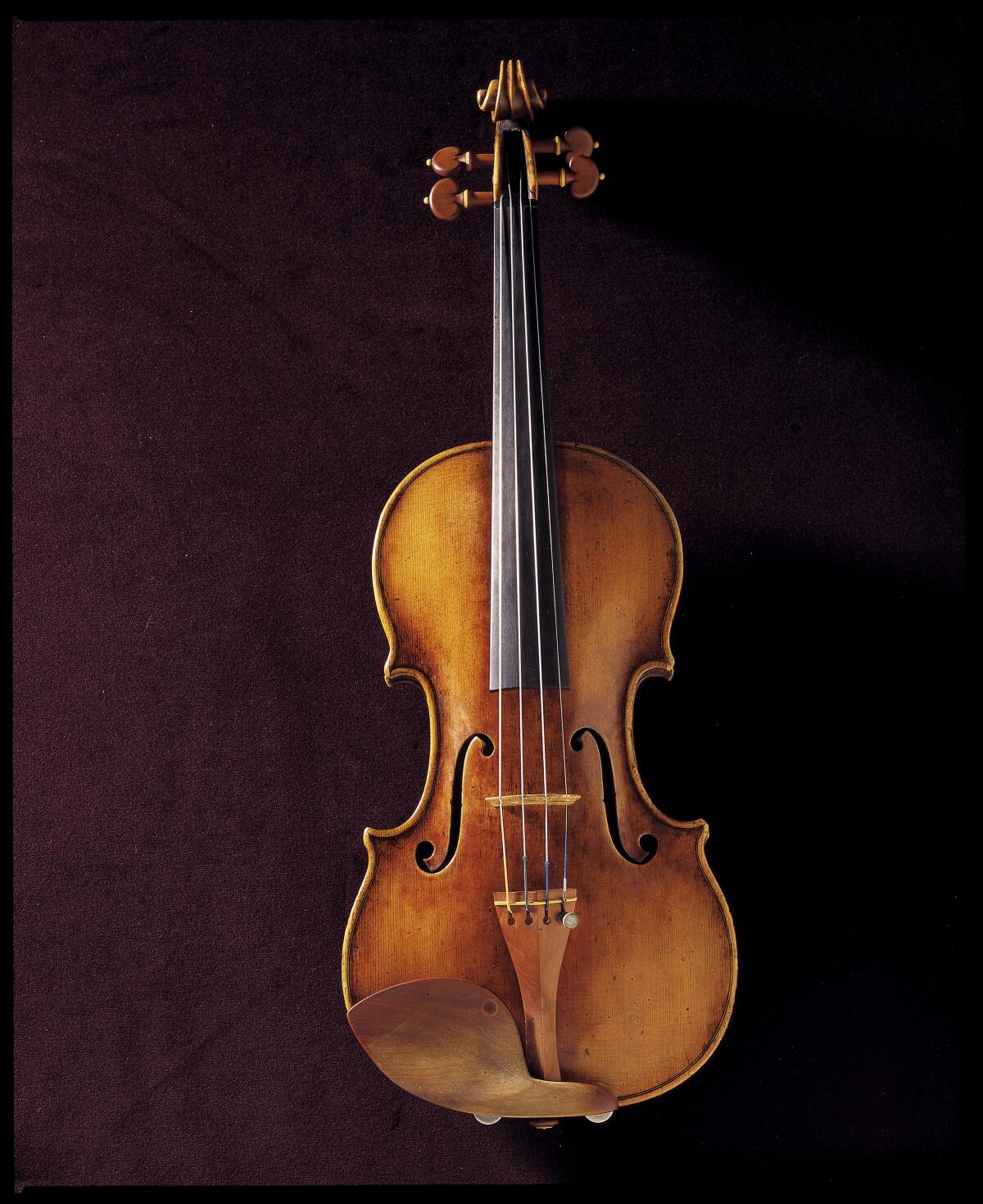

It would have been tempting to open the case right there. Perhaps Tupica leaned down, popped the two fasteners and lifted the lid. Sitting snugly within the case’s plush green velvet lining were two violins and two bows. One violin looked far older than the other; its wood had aged amber-brown beneath worn varnish with plum-red remnants. Tupica picked up the case by its leather handle, put it in her T-Bird and drove off.

By the time I learned about Tupica she was dead. Having missed her by nearly two decades, I could not ask her what she thought when she opened the instrument case, or when she peeked into the f-hole carved into the belly of the older violin.

Squinting into the dimly lit interior cavity, Tupica would have seen the old rag-stock paper label, which bore the Latin version of the maker’s name printed in black ink.

It was an f-hole, or sound hole, not unlike the ones I have carved on many violins. Squinting into the dimly lit interior cavity, Tupica would have seen the old rag-stock paper label, which bore the Latin version of the maker’s name printed in black ink, still affixed with brittle hide glue to the violin’s maple back. And this was not just any name; it was the name in the violin world: Antonius Stradivarius. Did she recognize the pedigree straight off? Could she have missed it somehow?

Tupica was 57 the day she found the violin. She never married. She had no children. After more than 30 years of teaching Spanish, she was enjoying her recent retirement. I thought of her as a spinster. Beyond that, though, my imagination could not muster any flesh on her bones. That is, until I began talking to several of her former students and fellow faculty at South Pasadena High School.

Miss Tupica was the Spanish teacher everyone wanted. By several accounts, she was more than beautiful. She was striking, a free spirit. Tall and elegantly dressed, she exuded confidence when she talked and moved. “She didn’t walk; she strolled,” one former student told me. On school days, she arranged her long, wavy brown hair in a stylish bun, into which she regularly stuck a pencil. Good-natured but strict, she “could wither you with a look if you talked in class,” the student recalled. She taught sitting on a tall stool and exercised complete control over her class.

But Tupica wasn’t all seriousness. Her T-Bird convertible and tales of youthful surfing at Los Angeles beaches on a redwood surfboard made quite an impression on her teenage students. One who knew her particularly well told me that Tupica also played the violin and viola. “Her warmth and great humor, combined with her unconventional lifestyle, made her the constant subject of fond gossip. I haven’t met anyone before, or since, who had such an impact on me. And I’m not the only one.”

For 11 years Tupica kept her freeway find. Each time she held or played the Stradivarius, the moisture and salt from her skin left their invisible traces, absorbed into the instrument’s wooden cells. Tupica, like others before her, subtly wore away the varnish, the spruce and the maple, transforming the violin’s appearance into the sum of those encounters.

Surely, she must have asked herself how the violin had ended up on the side of the road. When she edged toward sleep, when she played it, when she drove by the place where she first saw it, Tupica must have flipped the facts around in her mind and considered the possibilities. Was the violin stolen or abandoned? Why was it dumped among the freeway jetsam? If someone had thrown it out, maybe she thought it was her destiny that the violin had come to her, to enjoy and to protect. Was it tossed from a passing car by design, for some strange revenge? Had it landed on the freeway by mistake—left on the roof or trunk of a car by an unwitting driver?

However the different scenarios swirled like snowflakes in Tupica’s mind, they evidently came to rest in a way that let her comfortably proceed with her life, keeping the violin as her own.

The Stradivarius sat stranded under Tupica’s bed until shortly before she died from colon cancer at the age of 68, in April 1978. She lived with her mother, Wanda, on North Maltman Avenue in Silver Lake. The house, Tupica and her mother are now gone. Only the violin remains.

There is nothing in the files of the Los Angeles Police Department to indicate that Tupica ever reported her discovery. But for a week in August 1967, a musician named David Margetts ran an ad in the “lost and found” column of the Los Angeles Times, among the notices for missing dogs, cats, cameras and jewelry, where he sought the violin’s return. He offered a “liberal reward,” no questions asked.

To Margetts’ great disappointment, a heartache that would continue for the next 27 years, he never heard a word about the Stradivarius. It simply had vanished as far as the world was concerned—a loss that would foreshadow another that may be about to unfold.

*

Petaluma, January 1994 Joseph Grubaugh and Sigrun Seifert, husband and wife, worked side by side in their Northern California shop, surrounded by violins, violas and cellos. Jars of powdered pigments, varnish, brushes and a fantastic array of hand tools populated the workbench. Books on violin makers and violin making packed the shelves. Wooden billets, planks and wedges of spruce, maple, willow and poplar leaned against the walls. An apron, stiff with a tough, skin-like brown patina from years of accumulated dried glue, violin varnish and wood dust, hung from the edge of a workbench.

Joe, Sigrun and I were often in touch, our friendship forged during our early days of violin making. At the back end of two decades, they were experts in restoration and authentication and had carved their way through countless new instruments of the highest quality, drawing out color with fine sable brushes on the instruments’ bellies and backs.

Into their shop walked Michael Sand, a longtime client, holding an old double-violin case. After discussing a Bavarian violin that needed repair, Sand picked up another that had been resting inside the case in plush green velvet. He handed it to Joe without comment.

Joe scanned the carved landscape of the spruce belly. “I was struck by the appearance of sepia retouching on every grain on the center of the belly,” he told me. “It had been poorly repaired.”

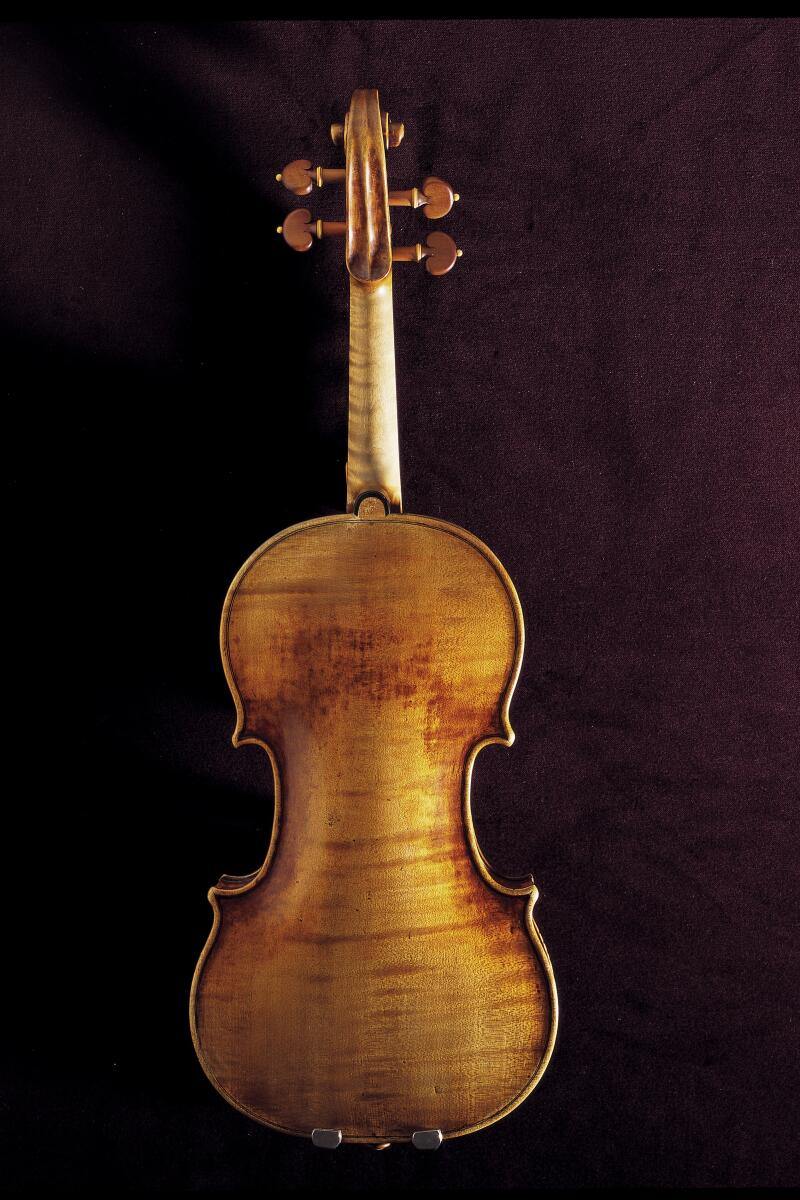

When Joe turned the instrument over to look at the back, his interest was piqued, though not because he saw flawless workmanship. The carved arching and sculpted edgework were clearly the products of an expert hand—but one past its prime, Joe later explained, “like an older dancer lit by a candelabra, a flickering beauty.”

The purfling caught Joe’s attention as well. Made of three thin strips of wood glued together, black-white-black, it was inlaid into a thin groove cut into the perimeter of the belly and back, emphasizing the elegance of the violin’s form. At each of the four corners, the purfling joined at a miter known as the “bee sting.” The purfling Joe saw was of uneven thickness, yet extremely graceful; each bee sting was unique and compelling in its execution.

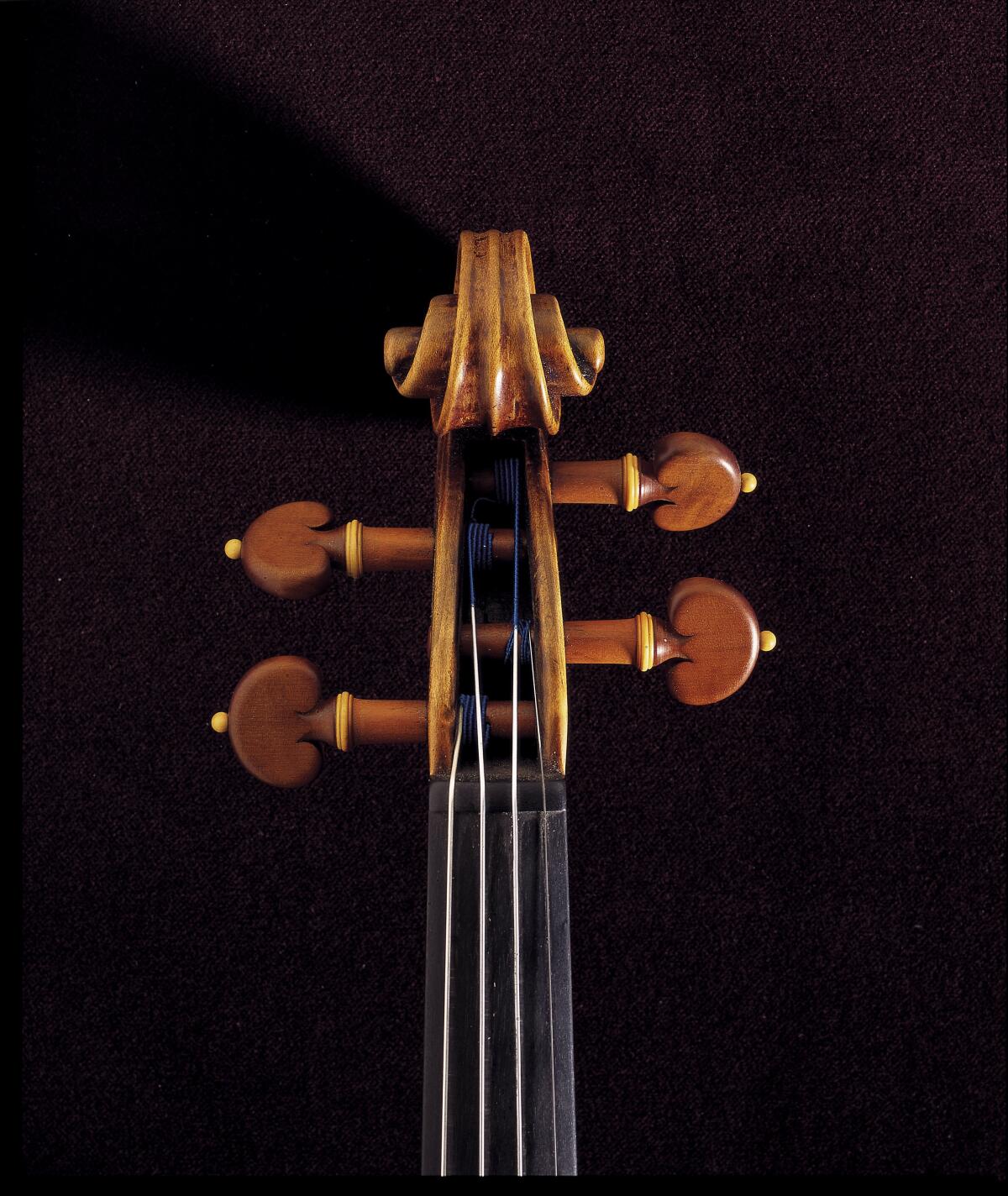

The wood-worn scroll, with remnants of plum-red varnish, was stunning. Joe’s blue eyes followed the nautilus-like scroll with excitement, from its outermost curve to its vortex, over the three gracefully carved spiral revolutions. Joe inhaled the visual information in all its subtlety, etching what he saw into his mind for possible later use when he would take sharp gouge to crisp maple. It flowed from the violin into Joe’s thoughts, and right down through to his woodworking fingertips.

The top of the f-holes looked very Strad-like, but Joe was thrown by the lower portion. The lines there looked over-tightened and clumsy compared with most Strads.

“It was then that I looked at our customer’s face and saw him looking at me,” Joe remarked. “He had been playing the violin and had suspected it was special.” Joe told Sand that he thought the violin was a late Strad, with maybe a touch of Strad’s son, Omobono. Sand then told Joe and Sigrun about his student, Teresa Salvato, and how she had come by this violin: Salvato’s ex-husband’s aunt had found the instrument along a freeway exit in Los Angeles. “It was a story that I gave little attention to as it sounded quite farfetched,” Joe recalled.

Then he peered through the f-holes into the dim cavity and saw a label that bore the familiar—and relentlessly forged—name: Antonius Stradivarius.

The date on the label was difficult to read; it looked like 1721 or 1727. But Joe was struck by the fact that Strad’s work in those years did not match the style of the f-holes cut into the belly. He thought that the label might have been altered. Was the instrument an impostor, the real deal or a composite—part lie, part jewel?

At that moment, Sigrun came into the shop and studied the violin. A few of the seams were open and needed gluing, so she and Joe offered to carry out this work and to study and photograph the instrument over the next few days. Sand agreed. Through the window above his chisel- and gouge-strewn workbench, Joe watched Sand drive off. When he was out of sight, Joe picked up the violin by its maple neck. Sitting at his workbench, he scrutinized every attribute of the instrument. He sought to make sense of the date on the label and his feeling that something was awry.

As the morning slipped by, Joe continued to try to unravel the violin’s identity. He grabbed a hefty tome called “Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari,” by Herbert Goodkind, and leafed through its 780-page record of Stradivari’s prolific life. He flipped forward to 1727, a few years shy of the time frame that Joe thought fit the style of workmanship for the violin he had before him. Three-quarters of the way through the book, Joe studied the details of violin after violin, bearing the names of prior owners or some mythological reference—the Kreutzer, the Dupont, the Maurin, the Venus, the Triton. No match.

He worked his way through the photographs, and as he did the years of Strad’s violins passed—1727, 1728, 1729, 1730, 1731, 1732. Joe scrupulously probed the instruments’ intricate features: the scroll, the outline, the purfling, the arching, the unique appearance of each piece of wood. Then he hit page 657. And there he saw it: a black-and-white mug shot of the very violin that he held in his hands.

Joe’s eyes widened, the arch in his animated eyebrows hiked upward. His heart raced as he looked back and forth between the photograph and the violin he held. The grain and figure on the spruce top and maple back, like fingerprints, were a dead giveaway. The elegant lines of the scroll and the bee stings also matched. The violin in the photograph was made in 1732. It was dubbed the “Alcantara.”

But that was not the date on the label inside the instrument. Joe turned his attention to the marred label. “At the lower edge, the paper had been scraped away, obliterating what looked like the top part of some script. I remembered that late in Strad’s life and career, he had written ‘D’Anni’ followed by his age.”

Joe’s leather shoes crunched on the curled white spruce chips scattered about the floor as he walked to his tall bookcase. He pulled down a copy of “Antonio Stradivari: His Life and Work,” by W. Henry, Arthur and Alfred Hill, and quickly found an entry stating that it was not until 1729 that Strad started using the last version of his label. On it the old master used a larger type font and substituted the Roman “v” in “Stradivarius” for the cursive “u” in “Stradiuarius,” which he had previously used. Joe looked inside the violin—the printed label in the violin bore a “v,” yet the year on the label predated 1729.

The Hills noted that when Strad turned 88, in 1732, he started to record his age in handwriting on the bottom of his labels. Had someone tried to remove Strad’s handwritten “D’Anni 88”? Violins made during his “Golden Period,” from 1700 through 1720, fetched a higher price than ones made early or late in Strad’s life. Joe suspected that someone had modified the original label in order to boost the value of the violin.

Legend has it that this instrument was once a possession of the Duke of Alcantara, an aide-de-camp to King Don Carlos of Spain. The word alcantara means “bridge” in Arabic.

By the late 1920s, the instrument had made its way from a Parisian violin shop to a Swiss collector to the New York violin shop of Rudolph Wurlitzer. The violin was sold in 1929 to Ilya Schkolnik, who performed on it as concertmaster of the Detroit Symphony and later the Baltimore Symphony.

The Alcantara traveled westward when Schkolnik moved to Los Angeles. In 1958 or ‘59, an oilman named Milton Vedder bought it, but he passed away shortly after. Vedder’s widow, Genevieve, first loaned and later donated the violin to UCLA, where W. Thomas Marrocco, professor and violinist in UCLA’s Roth String Quartet, performed on the Alcantara in the U.S. and abroad from 1961 until 1967. David Margetts then played it during the summer of 1967, just before it disappeared.

*

Cremona, Italy, 1732 In his 88th year, Stradivari created the Alcantara in Cremona. The luthier had carved more than 1,000 instruments by the time he selected the wood for this violin.

With gouges, small curved-bottom planes and metal scrapers, Strad sculpted the outside arching of the spruce belly and flamed maple back, and then carved out the inside of each plate, flexing and listening to the nearly weightless shell-like pieces of wood. The old man cut two f-holes in the belly: an exit for the sound, an entrance for light. He finished the bare wood torso of the Alcantara before he applied his amber-colored varnish, which often bore shades of orange and red.

A violin “in the white” is an unearthly thing—a creamy figure, almost ghostly, that looks as if it could not have been sculpted from mere wood.

In Strad’s skillful hands, the bits and pieces were now unified into a whole far greater than its parts. He hung the Alcantara from a line in his open-air roof terrace to be sunned, changing its direction so the morning and afternoon rays would have equal time to tan the violin’s body.

As each coat of varnish was brushed on the surface and hung to dry, small insects and dust settled on the aromatic, drying film and got stuck. The old man rubbed away some of the debris and continued with a new coat until the color was to his liking. He kept the overall thickness of the varnish to a minimum so as not to cinch the violin’s body, choking the sound. The Alcantara would remain encased in this protective coating until, little by little, players, collectors and others would wear portions of it away.

Stradivari carved an ornate and delicate maple bridge to fit the curved top, over which four strings of sheep gut sat, exerting pressure on the belly. He cut the sound post, a vertical dowel of spruce with wood grain perpendicular to that of the belly, to fit the inner arch of the cavity slightly behind the treble side of the bridge foot, a highly sensitive part of the violin’s nervous system.

As the old man strung up the instrument, turning the pegs clockwise, the tension increased and the violin creaked under the unfamiliar pressure. These were the Alcantara’s last mute moments.

The sound of wooden strain continued until he strung the Alcantara up to pitch, in fifths. The violin spoke as a snakewood bow, strung with horse hair and powdered with rosin, was drawn across the strings. It was then that Strad met what he had made. It was a transporting moment of creation itself, from silence to voice.

*

Petaluma, 1994 A week after Sand left the Alcantara with Joe and Sigrun, he returned to their shop. Sigrun was on the telephone with a customer, but she handed Joe a three-ring binder that contained the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers’ “Missing Property Registry.” Joe flipped to the index and looked up Antonio Stradivari. Three instruments were listed. He turned to the first Strad entry. It was a different violin. He flipped to the second Strad on the list—No. 208. It read in part:

Maker: Stradivari, Antonio

Inst: Violin

Origin: Italy

Owner: Music Department

Date reported: 12/08/67

Address: U.C.L.A.

Date stolen: 08/02/67

City Stolen: Los Angeles

Label: dated Cremona 1727

Descr: Known as the “Duke of Alcantara.” Described in Doring, “How Many Strads?”, p. 171. Good condition. Stolen with Poggi violin and Tourte and Fischer bows in Jaeger double case with green lining.

The blood drained from Joe’s face. He turned the binder around so Sand could read the entry for himself and watched him as his eyes followed the typed lines.

“Why don’t we hold on to the violin until this is cleared up,” Joe said.

Sand declined the offer. He reassured Joe that he would tell his student, Teresa Salvato, what had happened. Joe and Sigrun reluctantly surrendered the instrument. Then Sand left with the violin.

*

Oakland, 1994 Minutes after Sand drove off with the Alcantara, the phone rang in my 23rd-floor office.

“Hi, it’s Joe.”

I slouched into my chair, glad to hear my old friend’s voice, although these days I found myself constrained by a dark pinstriped gabardine suit and uncomfortable black heels. Six years earlier, in 1988, I had started my life as a litigator in a large Bay Area law firm. I had not given up violin making, but I let the dust grow thick on my tools as I was initiated into the high-pitched and exhilarating tempo of a full-time legal practice. By the time Joe called, my enthusiasm had faded as a stifling focus on the bottom line had distorted the very notion of time. I knew that Joe was not measuring his life in six-minute increments like I was.

I had met him in 1977, when he came into the San Francisco violin shop where I worked at the repair bench. Joe was looking for a job, toting along a bass he had made as an example of his work. In those days, we were part of a small group of violin makers living in the city. We often got together over dinner to discuss the intimate details of our craft. The art of violin making dawned in Italy in the mid-16th century, flourished through the mid-18th century and then withered. We mused about the “secrets” of Stradivari’s varnish, how to plane pear wood down to 0.3 millimeters for purfling and how to remove the mucilaginous material from cold-pressed linseed oil.

Joe filled me in on the Alcantara, and we discussed a proposed course of action, which included notifying UCLA that its violin had surfaced 27 years after its disappearance. Meanwhile, Sand told Salvato the news. The next day she called Joe and told him she was anxious to get the violin back to its rightful owner, but she demanded anonymity while she retrieved the instrument, locked it up and had her lawyer contact UCLA. The day after the call, Salvato flew from Los Angeles to the Bay Area and fetched the violin from her teacher. Joe and Sigrun quickly called UCLA, concerned for the instrument’s safety.

In the weeks that followed, a UCLA official had several telephone discussions with Salvato in an effort to get its violin back. At first, Salvato indicated that she would consider returning the violin if UCLA reimbursed her for expenses incurred for the instrument’s upkeep. “She didn’t want to keep stolen property,” Sand told me. One of the reasons she had asked him to take the violin to Joe and Sigrun, he said, was to find out if the instrument had been stolen in light of the strange story about how it was found.

The university provided Salvato with documentary evidence of its ownership of the violin, a gift from the late Genevieve Vedder. Salvato, though, was unmoved.

“They sent a letter . . . which did not, in my opinion, constitute title,” she later told me under oath in a deposition. “That—that letter looked like it may have been bogus. I’m not a judge of handwriting or letters, but I didn’t trust that flimsy piece of evidence, if you will. . . . I did not consider that letter to be a real piece of evidence. I considered it to have been something that anyone could have scratched out at the last minute. I did not know who Mrs. Vedder was. There was no reason I should know who Mrs. Vedder is. They said there was this Mrs. Vedder and she wrote this letter. There’s no reason I should believe that in light of the fact that they were trying everything they could to harass this instrument out of me.”

UCLA continued to urge Salvato to turn over the violin. She continued to resist. Finally, Robert Portillo, then-curator of UCLA’s Lachmann Collection, had had enough. “Where is the Strad?” he pointedly asked her.

“The instrument is elsewhere,” Salvato replied. “I’m not trying to keep it. If there is any possible legal way I could keep it, I wouldn’t refuse it.”

Later, Portillo pressed her again. “I thought you wanted to get the violin back to us?”

“I don’t have it in my possession,” Salvato said, warning that if she revealed the Strad’s whereabouts, it would “be in Switzerland before anyone can do anything about it.”

*

The back and stem of the Alcantara Stradivarius violin. (Pornchai Mittongtare / For The Times)

Los Angeles County Superior Court, 1994 Salvato’s threat catapulted her and the university into a lawsuit.

As the only violin-making attorney anyone had ever heard of, the case was custom-made for me. To say I wanted to help get the violin back was an understatement; the marrow in my bones led the way. After a serpentine journey through the internal workings of my law firm, which did not immediately see the merits of developing an expertise in “violin law,” we were hired to represent the university.

Despite my background, I had never filed suit to recover a missing violin, nor had anyone else I knew. I found my legal theories buried in endless stacks among disputes over pigs, poultry and steam shovels, and drafted the necessary papers. Because there was a risk that the violin might be spirited out of the country—a threat that Salvato later claimed was misinterpreted—I scheduled an emergency hearing in Los Angeles County Superior Court. I was joined by university in-house counsel Eric Behrens, whose own musical lineage gave him a real passion for the case; as it happened, Behrens’ grandfather, Hans Kindler, was a famed cellist and conductor and the founder of the National Symphony Orchestra.

The judge granted our request that Salvato be prevented from transferring the violin outside California. The parties agreed that the Alcantara would be deposited in a vault at UCLA’s Fowler Museum within three days, not to be played or handled until the battle for ownership ended.

The litigation machine ground forward, and Salvato’s ex-husband, who made no claim to the violin, told me in a deposition how the Strad came into his hands:

“The first time I heard about it, I was with my aunt. I had gone to see her. She was dying. She was in extreme pain. She was on her deathbed, basically. And she knew that I was studying music. And she told me she had some violins that she wanted me to have. . . . She had violins under her bed which she was unable to get. So she had her mother look under the bed and pull out the violin case. And she gave them to me. She told me at that time that she had been driving on a freeway years before, had thought she’d seen a dead body. She stopped to investigate, and it turned out to be the case.”

“Now, were you married to Ms. Teresa Salvato on the date your aunt gave you the Strad?” I asked.

“No.”

“What date did you marry Miss Salvato?”

“August 9, 1980.”

“Did you at any time ever transfer what you believed to be ownership to Ms. Salvato of the Strad?”

“My understanding is that she obtained possession as part of the divorce.” Given that his own musical pursuits didn’t include playing the violin, he explained, it made sense that she should have the instrument.

I met Salvato the day of her deposition, when she arrived at the Los Angeles branch office of my law firm. She was in her late 30s and had shoulder-length brown hair with bangs. Salvato exuded a sense of self-righteousness and hostility through dark brown eyes. She told me she had never met Nadia Tupica, but had heard the story of how she found the violin.

Salvato knew that the violin bore a Stradivarius label, but claimed uncertainty as to its authenticity. However, at least one musician who had played the Alcantara while it was in Salvato’s possession was convinced that it was an honest-to-goodness Strad. Peter McHugh, former concertmaster of the Louisville Orchestra, had been Salvato’s teacher when she lent him the violin for several months. “After I played the Mendelssohn Concerto on it, I cried like a baby,” McHugh recalled. It was “smooth, as sweet as could be. . . . It was something I had a love affair with.” McHugh noted that he had contacted two violin dealers in the hope of tracing the instrument’s true origin. When a shop in Cincinnati confirmed that it was a Strad, he said, he sat down with Salvato and her husband and told them, “It’s the real thing.” Salvato recalled otherwise.

When I asked Salvato what she had said to UCLA’s curator in response to his requests that she return the violin, she answered: “I said that I needed proof of ownership. And that I needed to make sure that whoever ended up with it was the proper owner, not just some entity who decided that they were big and could pull this off . . . I said that if I were not careful about who I handed the instrument to, it would disappear.” As I probed, she asserted that her intent had been to safeguard the violin from others.

“What makes you think you have a right of ownership to the Strad?” I asked.

“My opinion is that I have effectively protected the instrument, more effectively than any of the previous owners. And that it was legitimately given to me.”

She must have really thought she had a chance of winning the lawsuit, however slim. Her attorney may have told her that even a slam-dunk case can be foiled by an unexpected twist of events, as black and white turn to gray. Salvato wasn’t going to give up the Strad. Not without a fight.

*

Los Angeles, Aug. 2, 1967 UCLA’s resident Roth String Quartet had just finished rehearsing several pieces by Beethoven when, around 10 p.m., David Margetts loaded into his Corvair Monza the oblong violin case with the plush green velvet lining that held the Alcantara. That, anyway, is how he would recollect it.

“I remember setting the objects down so I could unlock the door,” he’d later testify. “I remember putting in my briefcase, the single fiddle case behind the seat, the music stand, and then putting the Strad in the car.”

On the way home, Margetts stopped at a convenience store to pick up some milk and orange juice. He left the driver’s side of the car unlocked, figuring he could see the car from inside the store. “There was a car parked to my right side with a single occupant in it,” he recounted. “I think it was a woman.” Margetts returned to his Corvair, placed the groceries in the back seat, hopped in and drove farther north. He then made another stop at Gus’s Barbeque in South Pasadena.

After parking by the front entrance, Margetts said, he locked the driver’s side, went in and ate a snack. It was about 10:30 p.m. Roughly 15 minutes later, he returned to his car. “I remember unlocking the driver’s side and getting into the car and arranging the groceries so they wouldn’t fall over. And I noticed the violin wasn’t there. It wasn’t in the car. . . . I panicked.

“The hours immediately following the disappearance, I wasn’t sure. You think of all kinds of things. Did I leave it on the street? Did I give it to Cesare? Did I leave it on the couch? . . . When I talked to Cesare a second time, I remembered that I had put it in the car. . . . I did remember putting it in the car.”

When Margetts discovered that the Alcantara had vanished, he rushed back to the cellist’s house, where the rehearsal had recently ended. He looked everywhere for the violin, which was on loan to him from UCLA, but found nothing. He drove to the police station and made a report of the incident at about 12:40 a.m.: “The violin was lost at the vicinity of Outpost Drive and Outpost Circle at about ten or ten-thirty. It is possible the violin was left on the back of the car and fell off.”

Margetts quickly sent out more than 100 notices to pawnshops in Los Angeles, southern Orange County, the San Gabriel and San Fernando valleys and the Westside, and to more than 50 violin shops in the U.S., Germany, Italy, France, Spain, South America, England and Japan. He ran an ad in several newspapers, including the one in The Times. UCLA officials joined Margetts in the hunt and contacted the LAPD and FBI, concerned that the Alcantara might be smuggled out of the country.

Margetts continued to do everything he could to get the Alcantara back, and was haunted by its disappearance. He never stopped searching, even as the decades passed and Margetts moved to Fresno to teach and perform music. When asked whether he ever got any leads on the violin, he replied, “No, no indication, no whisper, no information.”

*

Westwood, 1995 Contrary to what children say on the playground, finders are not always keepers. Not according to the law, that is.

Nemo dat qui non habet. He who hath not cannot give. A thief is not capable of obtaining good title through his misdeed. Nor can a thief pass good title. If someone had stolen the Alcantara from Margetts’ car, the thief could not obtain or pass good title to the violin. If Tupica was the finder of lost property, she could not become the rightful owner unless she had made the requisite legal effort to find the true owner. If a finder fails to make that effort, the finder may be guilty of theft, just as if she had pilfered the item.

No matter which route the analysis flowed, the result was the same: The Alcantara had been obtained by theft. Tupica’s possession of the instrument was unlawful, and so was Salvato’s.

Once started, lawsuits have a life of their own. The facts percolate to the surface through a Rube Goldberg-like design we call our legal system. In addition to fighting UCLA’s claim to the violin, Salvato went on the offensive and sued the university. She alleged, among other things, that the university’s efforts to recover the instrument had inflicted severe emotional distress upon her and that she was entitled to compensation. Deposition after deposition, motion after motion, the files and bankers’ boxes of documents grew and grew.

Nearly a year ticked by. Just days before the court was to hear a pivotal motion I had filed on behalf of the university against Salvato, I received a call from her attorney. She wanted to settle. Maybe she was afraid she would lose the motion, which might have resulted in a judgment for UCLA. Possibly her money for the battle had run out. Perhaps she had a change of heart.

The offer was too good to refuse. UCLA paid Salvato $11,500 in exchange for the Alcantara, whose value was pegged at about $800,000. Other claims relating to the second violin and two bows found in the case, as well as Salvato’s cross-claims, were also settled. (She declined to be interviewed for this story.) The Alcantara was returned to UCLA’s music department in December 1995.

Two months later, UCLA sent out finely decorated invitations for a celebration concert in which the Alcantara would be played.

Joe, Sigrun and I flew to Los Angeles for the event. The chancellor’s residence on the Westwood campus was crowded with people I didn’t know, enjoying hors d’oeuvres and wine. Alexander Treger, the concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, stepped up to the grand piano and opened the case that sat atop the piano’s lid. Inside lay the amber-colored Alcantara.

Treger lifted the violin, and the room fell silent. As his rosin-laden bow crossed the strings, the violin’s centuries-old voice, sweet and warm, swept over the guests and filled the room. Captivating but fleeting, the sound was one I savored. At the conclusion of his performance, Treger stepped up to me and graciously handed me the violin I had longed to hold and observe. People crowded around closely from all directions to see.

I tried to take in the belly, its f-holes, the back, the curve of the archings, the purfling and its bee stings, the nautilus-like spiral scroll, the plum-red varnish that thinned to the color of warm honey. I tried to absorb every subtle facet of the Alcantara, but the light was poor. It was hard to see the detail, and I felt pressured as all eyes focused on the violin in my hands. I was not ready when I handed it back. But the time had come and gone. The chatter of the crowd heightened. People ate and people drank. My eyes closely followed Treger as he methodically slipped the Alcantara into its oblong case with the green lining and closed the lid.

*

Berkeley, 2006 Since the Alcantara’s homecoming more than a decade ago, it has been heard, played and studied by many, young and old.

UCLA faculty and alumni recently performed pieces by Elgar and Ravel on the Strad. The wide eyes of my young son and daughter, aesthetic fledglings, have deliberated over its curves. This wooden evidence of Antonio Stradivari’s remarkable creativity traveled nearly 300 years to get to them, slipping silently, inchoate, into their memories and that of all the others.

From this collective well, we draw.

But the Alcantara’s fate is now uncertain. I recently learned that steep reductions in state funding have led UCLA’s music department to explore alternate ways to finance student scholarships. Among the ideas it has considered: selling the Alcantara. The money from a sale would allow UCLA to buy numerous violins for its students to play. The proceeds would also fund many much-needed scholarships for years to come. In this way, the Strad gives if it stays or goes.

But for me, it’s likely that only memories will be left if the Alcantara is sold—of the worthiest of legal battles for a violin-making lawyer, where the prize was rare and ours; of the feel of the subtle slope and rise of the violin’s archings and scroll; of a sweet and transporting sound that washed over a room of people who listened in absolute silence; of a violin’s labyrinthian past that is more lost than found, filled with ghosts like Nadia Tupica and a Spanish duke. I cannot pierce the past’s barrier and retrieve those who are gone forever, but I can sense them. The bridge that is the Alcantara, by name and deed, links the centuries and its inhabitants.

Who might buy the Alcantara? And for what purpose? In 1958, it was valued at $25,000; by 1995, the figure had increased more than 30-fold, and since then Stradivari’s work has continued to appreciate significantly. The 1687 Kubelik Stradivari commanded $949,500 at auction in 2003, and the 1699 Lady Tennant Strad sold in 2005 for $2,032,000, an auction record. Private sales of selected Strads have been even higher.

Perhaps the Alcantara would find its way to an orchestra or another public venue or a violinist who would publicly perform on it. If it is offered for sale, I’m hoping for a second rescue. Last September, the 1709 Viotti Stradivari violin was spared from private purchase by hundreds of donors in England so that it could be acquired by London’s Royal Academy of Music. But many of these instruments pass into the anonymous darkness of private hands for decades.

By hand, we create something from nothing. Be it a drawing, a meal, a story, a garden, a violin or the playing of a nocturne upon it. The reward may linger in our physical world, in this instance for hundreds of years. To make, to own, to covet, to play, to hear, or to see a thing of aesthetic beauty can be a wellspring of restorative power to those who crave it. To some, it is a necessity.

Years ago, I left the law firm in Oakland and eventually settled into private practice in Berkeley, where I now work. Over time, I noticed that the feeling in the fingers of my right hand began to numb, producing an infinite and alien distance between object and sensation. Numbness metamorphosed into searing pain, quieted only by the constricting blue chill of ice. I could no longer feel the lightness of flour or grasp a violin-making tool.

In an effort to revive my hand, its tissues were flooded with cortisone. It was dipped in hot wax to amplify blood circulation, leaving behind a discarded, pearly paraffin glove. My hand endured my denial and the ravaging passage of time until I begged a surgeon to cut open my most venerated tool and fix it.

My hand left the operating table with a two-inch Frankenstein-like incision, laced with black stitches running from the wrist. The forearm turned black and blue and yellow. I could see for weeks the stain of blue ink drawn by the surgeon who had marked the path of his scalpel on my palm, and then two crossing blue lines that helped him reposition the two flaps of skin he had peeled back from either side of the life line, like the neatly folded wings of an origami crane.

The scar has now faded. My right hand can pull up the poison hemlock growing in my yard by its long crimson roots and carve the belly of a violin or an acanthus leaf in lime wood. By hand, I have come back to where I began. I am making a new violin, a Strad model.

Although I soon may no longer know where to find the Alcantara, it is in my mind and in my woodworking fingertips. With each pass of my gouge, I feel the blade as it stalls on hard winter grain, as it glides like butter through summer’s growth.

With each stroke of the hand, a crisp wood curl forms and lightly falls, and one by one they flood the workbench and crowd onto the floor until I am surrounded by a sea of fragile spruce spirals. I am seeking the yet-unearthed hourglass torso of a violin within rough-hewn timber.

Carla Shapreau is a violin maker and lawyer. She is the coauthor of “Violin Fraud: Deception, Forgery, Theft, and Lawsuits in England and America.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.