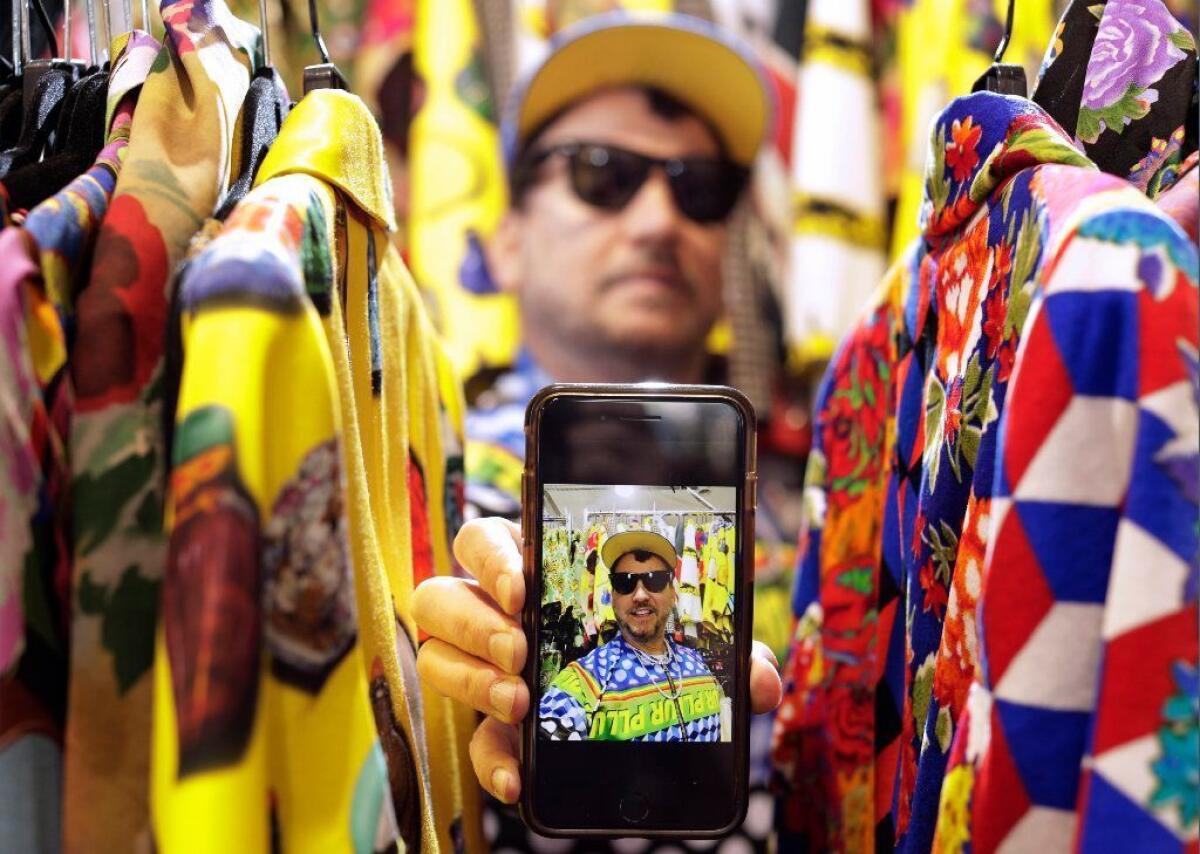

For Libertine designer Johnson Hartig, it’s time to come home

- Share via

When word went out earlier this month that Libertine would present its fall 2019 collection in Los Angeles, the media narrative seemed all but pre-written.

The iconoclastic label, known for repurposing vintage into crystal-embellished works of art, is joining a flurry of fashion houses that have held runway shows in L.A. in recent years — a subtle shift of gravity that drew Tom Ford to the West Coast during Oscar week in 2015, Hedi Slimane and his show for Yves Saint Laurent a year later, and, earlier this year, Rodarte, which staged its first hometown show at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in February.

Cue the chorus of boosters: Did you hear? L.A. is on the upswing!

But while Johnson Hartig, the 48-year-old designer behind Libertine, does allow that the timing felt right — New York Fashion Week had started to seem less and less exciting — his decision was equally rooted in acute personal anxiety over the ways that L.A. is changing.

“I feel a little bit of ownership,” Hartig explained last week at Libertine’s studio in Hollywood. “Like, ‘Hey, you didn’t run that new apartment complex by me.’”

Hartig was seated at a long white table, next to an enormous arrangement of silk fuchsia flowers. Large mobiles — an eyeball, a rainbow, a cigarette, a skull — hung from the ceiling overhead. Leaning against a wall nearby was a massive mosaic mirror he found in Myanmar and left partially unwrapped, so aesthetically pleasing was the avalanche of shredded newsprint it was shipped in.

Libertine has occupied its current space since 2016, but the company has been based in Hollywood for nearly two decades. Hartig has lived in L.A. since the 1990s, in Hancock Park for the past 13 years. During that time, he has seen many historical buildings razed.

Hartig has grown so vexed by the pace of development, in fact, that he recently called his city councilman. “Are you concerned about the city and what it’s going to look like five years from now?” Hartig recalled asking. “He didn’t feel like getting into a conversation with me about that.”

Concerns over land use have even creeped into Hartig’s therapy sessions. “My therapist would constantly say, ‘Johnson, you’re not the sheriff of Los Angeles. You’re not gonna get the traffic problem under control, or the development problem under control. Just breathe.’”

What Hartig could do, he decided, was represent his Los Angeles. So he set out to find a location for Libertine’s next show, settling on the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Hancock Park — “a spectacular building I’d driven by 10,000 times but had never been in until last month.”

If Hartig’s motivation for showing in L.A. is partly melancholic, the clothes are not. Not at first glance, anyway. His fall collection, the details of which are under embargo until the April 26 show, is an optimistic, very Libertine riot of flash and whimsy, crystals and sequins.

It includes pieces from Hartig’s collaboration with the Jimi Hendrix estate and a blazer cut from a cheery-looking print Hartig designed himself. The pattern features rows of black loafers, red rotary phones and a certain yellow book jacket on repeat: Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Being and Nothingness.”

Hartig grew up the fourth of five children, mostly in Whittier, with stints in Alaska, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia during his junior high and high school years. (His father worked for an oil company.) He studied painting and drawing at Cal State Long Beach, gravitating to the work of Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente. For a while in the ’90s, Hartig pursued acting with “a big mix of oddballs” that included his roommate at the time in Los Feliz, the (future) fashion designer Thom Browne.

“He was so creative, and so true to himself, and that really stood out in L.A.,” Browne said. “We were probably the only two people in L.A. who actually wore tailored clothing.”

Hartig got into fashion on a lark. “I would always buy things from Goodwill, take them apart and put them back together,” Hartig said. “It was something I did purely for myself.” He was wearing one such creation — Dickies pants on which he’d hand-glued tiny crystals — when a buyer from Maxfield spotted them and asked Hartig if he would make eight pairs for the store.

Shortly after Hartig delivered the first batch, Elton John bought one pair, R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe another. Maryam Malakpour, longtime stylist for the Rolling Stones, picked up subsequent designs — “men’s shirts with Victorian imagery silk-screened on them,” she recalled — for Mick Jagger.

Hartig officially co-founded Libertine in 2001 with New York-based artist Cindy Greene, who was then a graphic designer for DKNY and half of the electroclash band Fischerspooner. The brand found early fans in Damien Hirst, who sent pieces of art in exchange for Libertine clothes, and Karl Lagerfeld, who bought much of the label’s spring 2006 collection for himself.

Greene left the label in 2008, and Hartig has been leading it ever since, overseeing a series of collaborations and lately easing into e-sales. “His brain never takes a nap,” says Betty Halbreich, Bergdorf Goodman’s personal shopper. “He likes to sell when he’s not dancing on his head.”

If anyone can sell a more preservation-minded vision of L.A., at least to the fashion world, it could very well be Hartig, whose inimitable brand of chutzpah is somewhat legendary.

The first time Hartig met Anna Wintour, the fearsome editor in chief of Vogue, he informed her: “I have to tell you that I’ve been internalizing you as my mother. My therapist and I figured that out yesterday. So if you could tell me how much you like my clothes before I show them to you, it would be enormously helpful.”

To an encounter with Cher, Hartig once brought a fake letter he’d written to himself and asked her to sign it. “Dearest Johnson, You really are the greatest,” it read. “When I wear your clothes, I feel like I’m soaring through the clouds with angels.” (Cher signed it.)

But Hartig’s show promises to be more tribute than sales pitch, says his friend and sometime collaborator Katherine Ross, founder of the Wear LACMA program.

“Whenever a designer has done a show here, it does always seem like a celebration, not only of their work but of the city they love,” Ross said. “Johnson has always been here.”