California water managers have announced their preliminary forecast of supplies that will be available next year from the State Water Project, telling 29 public agencies to plan for as little as 5% of requested allotments.

The state Department of Water Resources said Monday that the initial allocation is based on current reservoir levels and conservative assumptions about how much water the state may be able to deliver in 2025.

“We need to prepare for any scenario, and this early in the season we need to take a conservative approach to managing our water supply,” DWR Director Karla Nemeth said.

The Newsom administration is projecting that California’s State Water Project could lose up to 23% of its water delivering capacity within 20 years.

Last year, the state’s initial forecast was 10% of requested supplies, but the allocation was increased to 40% in the spring.

Officials said the initial water supply forecast does not take into account the series of storms that drenched much of the state in the last two weeks of November. The storms pushed precipitation to above-average levels in Northern California for this time of year.

“Based on long-range forecasts and the possibility of a La Niña year, the State Water Project is planning for a dry 2025 punctuated by extreme storms like we’ve seen in late November,” Nemeth said. “What we do know is that we started the water year following record heat this summer and in early October that parched the landscape.”

She said officials considered runoff forecasts that account for how the hot, dry conditions in the summer and October left soils parched. When soils are too dry, runoff from the mountain snowpack typically will be soaked up by the ground, reducing the amount of water flowing in streams and rivers to reservoirs.

A weak La Niña is forecast for this winter, and NOAA forecasters have said the pattern probably will bring drier-than-average conditions in much of the Southwest. They have also said, however, that the outlook is uncertain for much of California.

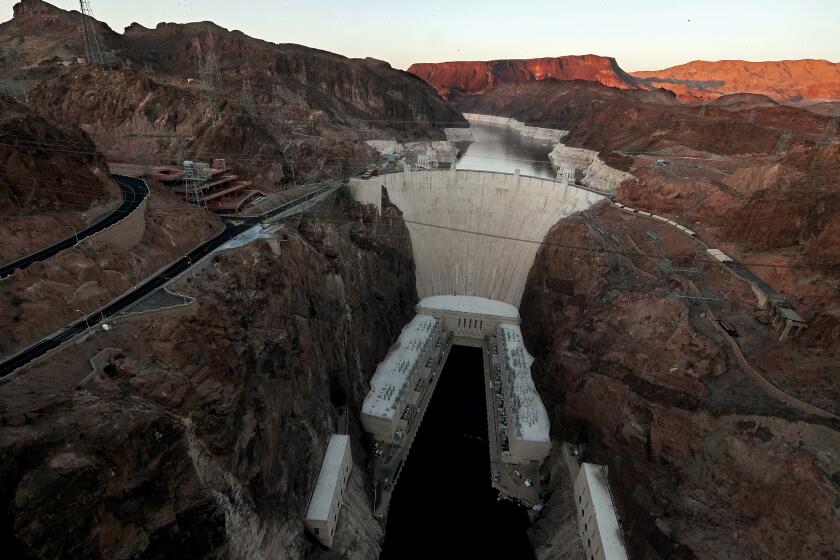

The State Water Project’s aqueducts and pipelines transport water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta to 29 water agencies that supply 27 million people.

Federal officials release a proposal outlining options for new, long-term rules for managing chronic water shortages from the overtapped Colorado River.

State officials update the allocation monthly and may increase their forecast based on the rainfall, snowpack and reservoir levels. A final allocation fis typically announced by May or June.

Although the initial forecast is relatively low, the allocation should increase in the coming months, said Deven Upadhyay, interim general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which supplies water for 19 million people across six counties from Ventura to San Diego.

Southern California is continuing to benefit from the enormous quantity of water that flowed into reservoirs during 2023, one of the state’s wettest years on record.

Diamond Valley Lake, the largest drinking water reservoir in Southern California, is 97% full. And the MWD is projected to finish the year with a record 3.9 million acre-feet of water banked in various reservoirs and underground storage areas.

“Our storage going into the end of the year is very good,” Upadhyay said.

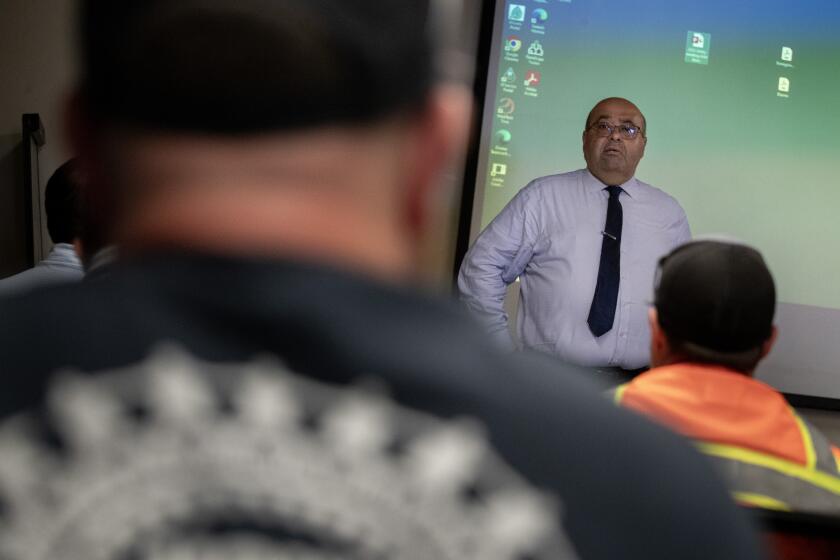

The Metropolitan Water District board extends the leave of absence of General Manager Adel Hagekhalil while an investigation of harassment allegations continues.

The region has been able to store such large reserves in part through progress on conservation and investments in expanding water storage, he said.

The stored water will help “buffer us in the near term” if 2025 turns out to be a dry year, Upadhyay said, while the agency focuses on efforts to prepare for the next drought and the effects of climate change.

He said that includes, for example, implementing California’s newly adopted rules setting long-term conservation goals for urban suppliers, and investing in a plan to build an $8-billion water recycling facility.

“As we’re thinking about water supply management, we’re less focused on the year to year variation, and we’re more focused on how do we invest in things that will allow us to be reliable for the long term,” Upadhyay said. “We want to make sure that we’ve got that long-term balance in view.”