Ian James is a reporter who focuses on water and climate change in California and the West. Before joining the Los Angeles Times in 2021, he was an environment reporter at the Arizona Republic and the Desert Sun. He previously worked for the Associated Press as a correspondent in the Caribbean and as bureau chief in Venezuela. Follow him on Bluesky @ianjames.bsky.social and on X @ByIanJames.

1

After years of analysis and debate, California regulators have adopted a nation-leading drinking water standard for hexavalent chromium, a carcinogen found in water supplies across the state.

The dangers of the toxic heavy metal, also known as chromium-6, became widely known in the 1990s after a court case that then-legal clerk Erin Brockovich helped develop against Pacific Gas & Electric for contaminating water in the town of Hinkley in the Mojave Desert. The story of tainted water in that case, which led to a $330-million settlement, inspired an Oscar-winning movie starring Julia Roberts.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The California Legislature in 2001 called for the state to develop a drinking water standard for hexavalent chromium. But the path to finalizing a standard involved years of debates over the health hazards and the costs of treating water to remove the carcinogen.

The State Water Resources Control Board voted unanimously Wednesday to set the maximum level for chromium-6 in drinking water at 10 parts per billion, a limit that state officials determined will significantly reduce health risks.

“The standard adopted today improves health protections for communities with impacted drinking water supplies,” said E. Joaquin Esquivel, the board’s chair.

Chromium-6 is found naturally in groundwater in parts of California, dissolving from certain types of rock into aquifers. The heavy metal is also an industrial pollutant and has been discharged from chemical plants, cooling towers and gas compressor stations.

Long-term exposure to chromium-6, which is odorless and tasteless, in drinking water has been linked to gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive harm and damage to the liver and kidneys.

Clean water advocates had urged the state water board to adopt a more stringent limit, but also said they supported setting the new standard because it was long overdue.

“This is a historic step forward,” said Nataly Escobedo Garcia, water policy coordinator for the group Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. “However, the board has failed to detail why a lower number is not achievable, which would only further protect the health of Californians.”

The state adopted a limit of 10 parts per billion once before, in 2014. But in 2017, a judge tossed out that standard, ruling the state hadn’t adequately studied whether the regulation was economically feasible for suppliers to implement.

That left the state without a specific standard for hexavalent chromium.

California has for years had a drinking water limit of 50 parts per billion in effect for all chromium compounds, including both chromium-6 as well as the significantly less toxic chromium-3.

Following the 2017 court decision, the state water board started over and conducted an analysis of economic feasibility to help develop a new limit. State officials studied various treatment methods and prepared cost estimates.

The board proposed the new standard in 2022. It said in a report that at the 10-parts-per-billion limit, a majority of Californians would see increases in their water bills of less than $20 a month, but that some small water systems would need to raise rates by closer to $40 a month.

The EPA has issued federal limits on dangerous “forever chemicals” in drinking water, which it says will save thousands of lives and prevent serious illnesses.

Members of the water board said they are concerned about water affordability, and they plan to work with small water suppliers to provide funds and assistance to help them meet the standard.

“It is going to impact affordability for many small systems,” board member Sean Maguire said. “The economic analysis shows that. And that’s what makes this decision so difficult, in part.”

The board decided on an implementation timeline that allows small water systems more time to comply with the regulation, which is expected to take effect by Oct. 1.

Under the timeline, large water systems with more than 10,000 service connections will have two years to meet the standard, while smaller water systems will have three or four years to comply, depending on how many customers they have.

Representatives of several water districts told the board that the new standard will require them to make large investments in costly treatment systems.

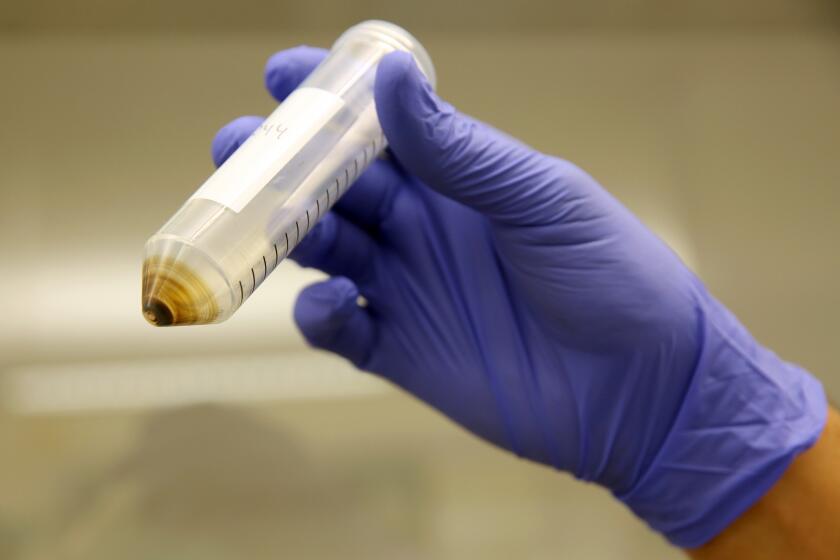

Because the well at their home in Exeter, Calif., is contaminated with chromium and arsenic, Maria Olivera’s family drinks and cooks with bottled water provided by the state.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

Managers of the Coachella Valley Water District said they estimate that installing treatment systems for 34 wells that now have chromium-6 levels above the limit will cost about $510 million, which would drive up rates dramatically for 270,000 residents in the Coachella Valley.

Joanne Le, the district’s director of environmental services, said that “significant state funding will be required” to implement the standard. She urged the state water board to make “a firm commitment to working with water systems to fund this effort.”

Representatives of small water providers also called for extra time and funding help, saying many communities will need to spend millions of dollars to come into compliance.

With water rates rising, many are struggling to pay. A Senate bill would establish a permanent program to help low-income customers who are falling behind.

But several residents who live with contaminated tap water said during Wednesday’s meeting that the state should put greater weight on protecting public health.

“I want to ask the board, what is the real cost when you have to say to someone, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, your child has cancer.’ Cancer caused by water that was polluted. What does that cost?” said Robert Chacanaca, who lives in Monterey County. “I would encourage you to do the right thing and give us clean, safe drinking water, regardless of what the economic cost is, because the human cost is far more greater.”

Chacanaca and others from his Central Coast community said their wells are contaminated with harmful levels of chromium-6, arsenic and nitrate. Some said they have neighbors who have been diagnosed with cancer.

“I’m here because the state water board has let us down,” Ana María Pérez said in Spanish. “Since 2017, we’ve been waiting for a chromium-6 level that will protect our health. And after all this time, they’ve left it the same. It’s not fair that many people have to get sick and even die.”

According to the state water board, there is an estimated 1-in-2,000 risk of developing cancer for a person who drinks water containing 10 parts per billion of chromium-6. That estimate is for a person who drinks two liters of water daily for 70 years.

Environmental justice advocates pointed out that the limit set by the state is still 500 times higher than the public health goal of 0.02 parts per billion, a target set in 2011 by the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

They argued the state should set a stricter limit. They noted that since 2012, California has formally recognized the human right to safe, clean and affordable drinking water.

“Public health and human rights are not something to be balanced in a cost-benefit analysis,” said Kala Babu, a legal fellow with the nonprofit Community Water Center.

“A cancer risk for 500 out of every 1 million people doesn’t sound very safe,” Babu said. “It’s low-income communities and communities of color that are carrying the weight of contaminated drinking water.”

More than a decade after California passed the Human Right to Water Act, about 1 million residents still lack access to clean, safe, affordable water.

Researchers with the Environmental Working Group have called for a target of 0.02 parts per billion to guard against cancer risks and have estimated that more than 35 million people in the state have drinking water with levels of chromium-6 higher than that level.

“The water board has failed the people of California,” said Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist for the group. “Chromium-6 is a known carcinogen — even at exceptionally low levels. It has no place in drinking water.”

Esquivel, the board’s chair, described the decision as striking a balance.

“There is opportunity and consideration to continue to do better, to be more protective,” he said. “But I’m comfortable with where we are currently.”

Board member Laurel Firestone said she would like to see the limit be lower, and thinks that should be done as part of a five-year review.

“There’s a number of technologies that I think could help really lower the costs, and could help make sure that more people could be protected,” she said.