Officials release map of hazardous fallout from refinery mishap

- Share via

When a Bay Area oil refinery released up to 24 tons of metal-laden ash over the Thanksgiving holiday, the pollution showered onto a nearby junior high school and may have traveled up to a dozen miles into neighboring communities that weren’t notified until months later, according to a new air district analysis.

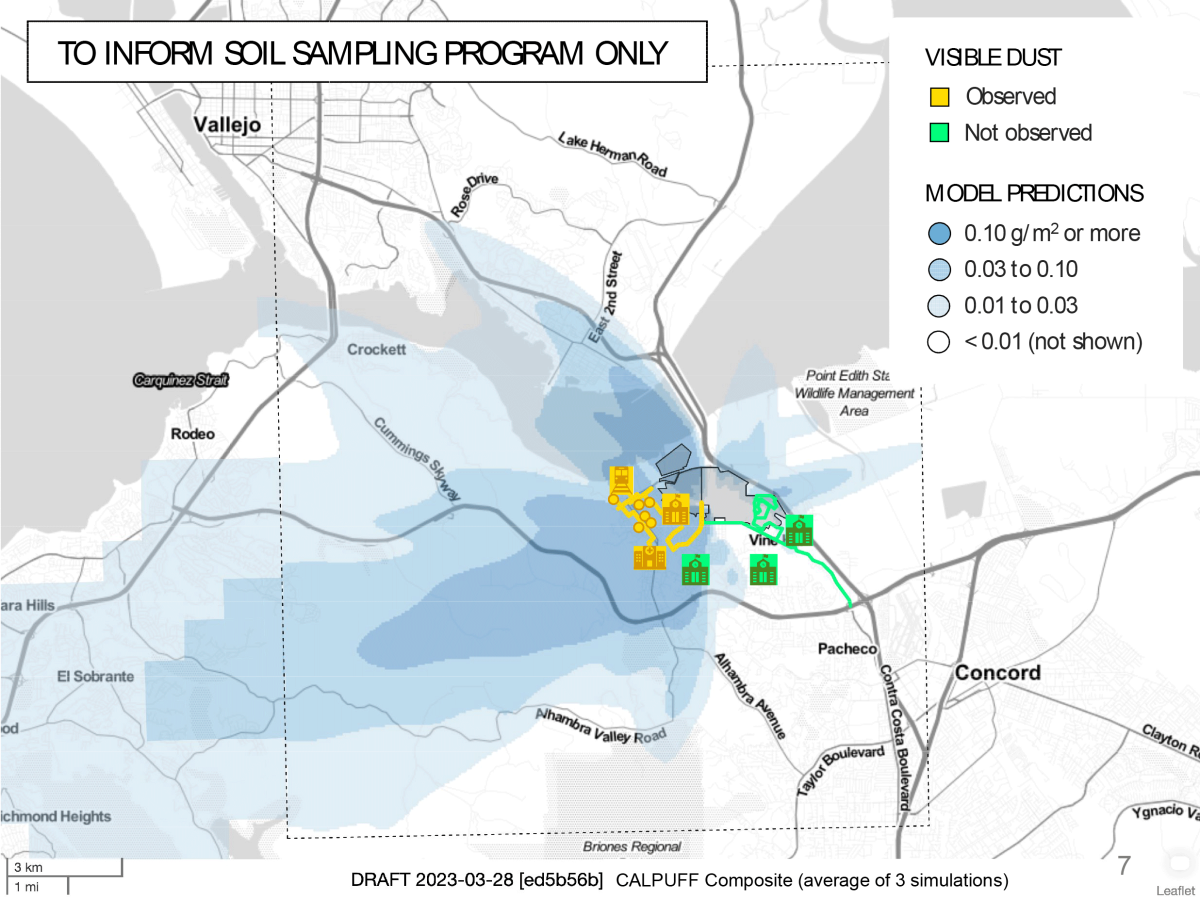

Four months after the hazardous materials erupted from Martinez Refining Co.’s smokestacks, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District recently presented a map at a Martinez City Council meeting illustrating the extent of the fallout.

The map is the first attempt by officials to identify how many homes, schools and other properties might need to have their soil tested by a consultant recently selected by the county’s oversight committee. Its publication comes amid mounting outrage from Martinez residents who have called for equipment upgrades and greater oversight at the refinery.

“I know it was a mistake to move to a town that has a refinery,” resident Elka Holmes said during a public meeting on the matter. A mother of two, Holmes moved into a home just blocks from the refinery two years ago.

“I breathed this in, my baby girl is breathing this in, my little boy is breathing this. All I have to say is just how much anxiety it’s given me, how much fear and how much of a feeling that I just need to flee this town,” she said.

In the Bay Area, this map from a report published by Bay Area Air Quality Management District details the extent of where hazardous materials may have fallen after Martinez Refining Co. released around 20 tons of spent catalyst in late November. This computer model shows accumulation of contaminants with shades of blue. The heaviest accumulation may have occurred west of the refinery, where it is shaded in a darker blue, while smaller concentrations may have traveled as far as Richmond, highlighted in the lightest blue.

Preliminary sampling revealed the spent catalyst contained aluminum, barium, chromium, nickel, vanadium and zinc. Contra Costa County Health Services has said the most significant health risks were short-term respiratory problems from breathing in the metals in the hours after the release. Exposure to high concentrations of these metals over a long period of time could cause more serious health problems, the agency said.

A spokesperson for the company said that Martinez Refining was aware of the map and “continues to cooperate with all agencies and investigations related to the November 24, 2022, spent catalyst release.” Because the incident is under investigation, the company is unable to comment publicly, said Brandon Matson, of PBF Energy, Martinez Refining’s parent company.

As investigators probe a hazardous materials release at a Martinez refinery, residents question why it took so long for officials to issue a warning.

According to the new map, the greatest concentrations of spent catalyst probably fell west of the refinery, an area that includes Martinez Junior High, according to the air district’s computer modeling. Hazardous material may have also traveled across the Carquinez Strait into the neighboring city of Benicia, and trace amounts may have drifted as far away as Richmond, the air district simulations show.

Air district officials said that the computer modeling was an “educated guess” of where pollution fell on Nov. 24-25, not an assessment of areas that might be presently affected by contamination. Since the refinery’s accidental release, heavy rains have poured over the Bay Area, probably sweeping contamination into other areas, the air district said.

The model, however, is expected to inform forthcoming soil sampling. The 11-member county oversight panel announced it has selected a firm, TRC Cos., to conduct a risk assessment, including the collection and analysis of soil samples. Results are expected to be published in May.

The air district and county said they saw spent catalyst at the city’s Amtrak train station, the Contra Costa County Health Center and Martinez Junior High School, which serves about 800 students.

Nicole Heath, the county’s acting director of the hazardous materials program, said information about levels of contamination and health risks associated with exposure won’t be available until soil sampling is completed.

“At this point, we still don’t know what we don’t know,” Heath said. “What the plume model was able to tell us was a general idea of where deposition occurred. That is not able to speak to the health effects or if there’s any potential health effects at the levels of what we would be concerned about.”

Martinez Junior High was not in session at the time of the hazardous release, according to Helen Rossi, superintendent of Martinez Unified School District. However, once students returned, they were still allowed to play outdoors for recess and physical education classes, and there has been no change to policy since the refinery release.

“We take direction from the health department and at no time did they state that it was unsafe for students to be outside upon their return to school,” Rossi said in an email to The Times.

Researchers theorize that a widely used degreasing chemical -- found in the soil near some residential areas -- may be linked to Parkinson’s disease.

But the hazardous materials release has put the fate of the school’s garden in limbo. In January, roughly a month after the incident, health authorities advised area residents not to eat fruits and vegetables grown in exposed soil.

Just before Thanksgiving, more than 200 sixth-graders planted winter seedlings, including sugar snap peas and cabbage, in four garden beds and two wine barrels, according to Chelsea Pickslay, community garden program manager for nonprofit New Leaf Collaborative. This spring, as in years past, the school garden was expecting to host community members who want to pick pomegranate, nectarines and other fruit from its 19 trees.

However, the vegetables that survived heavy rains have been deserted, the fruit remains unpicked and students have been kept out of the soil as well.

“The idea was that the kids would come back in the spring and get to taste and see their plants. But that all fell apart pretty quickly,” said Pickslay, who has sought donations to replace the garden with clean soil.

At a meeting of the Martinez City Council on Wednesday, residents voiced frustration over the refinery’s public statements after the incident, with some pointing to a Nov. 26 Facebook post by Martinez Refining, which claimed the spent catalyst was “non-toxic and non-hazardous.”

“This material appears as minute white particles that is easily removed by rinsing with water from surfaces such as, patio furniture, toys, and fruits and vegetables,” the post read. “There are no health risks associated with this material.”

PBF Energy declined to comment about the post.

Others noted that while city officials and residents have called on Martinez Refining to upgrade its pollution controls, the company has resisted.

In 2021, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District adopted a new regulation that requires petroleum refineries, within five years, to reduce the amount of particulate pollution released from their fluid catalytic cracking units, the equipment that processes crude oil into finished products such as gasoline.

But Martinez Refining, along with Chevron, sued the air district to challenge that rule.

Numerous homes that underwent remediation have been left with lead concentrations in excess of state health standards, according to USC researchers.

Martinez Refining continues to operate using an electrostatic precipitator to filter out particulates from its emission stream. However, the air district said wet gas scrubbers are a much more effective mechanism that could help refineries reduce this pollution and achieve the more stringent standard.

Electrostatic precipitators, like Martinez Refining’s, also are manually turned off when refining is not occurring, because if too much combustible material and oxygen are present, that could trigger an explosion like the one at Exxon Mobil’s refinery in Torrance in 2015.

On Nov. 20, the refinery experienced an “upset unit,” a malfunction that prompted workers to halt operations and turn off its pollution control equipment. When Martinez Refining restarted operations, it failed to switch this pollution control equipment back on, leading to the accidental release of spent catalyst.

Wet scrubbers, on the other hand, don’t need to be turned off, which might have averted the hazardous materials release.

“It’s true that you don’t necessarily have to turn your wet scrubbers off for safety reasons like you do these electrostatic precipitators,” an air district representative said. “There’s not a danger of sparking an explosion. But, would it have completely controlled this event had it occurred if wet scrubbers were in place? I have to think it would help. But I don’t know for sure that would have controlled all the emissions.”