- Share via

NEAH BAY, Wash. — Each year at this time, gray whales begin the roughly 6,000-mile journey south from their summer feeding grounds in Alaska to their calving and breeding lagoons in Mexico’s Baja peninsula.

This year, an administrative trial in Washington state could dictate whether the Makah tribe can resume hunting the whales during future migrations.

The Makah, who live in the Olympic Peninsula’s northwest corner, Neah Bay, have asked the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for a waiver from the Marine Mammal Protection Act so they can restart their traditional whale hunt, harvesting up to 20 animals over the next 10 years.

They are supported by the federal government and tribal communities around the globe, who point to an 1855 treaty specifically granting the Makah the right to hunt whales. In return for $30,000, and the ceding of 300,000 acres, Washington’s then-Gov. Isaac Stevens granted the Makah “the right of taking fish and of whaling or sealing.”

The Makah are the only U.S. tribe with whaling specifically mentioned in its treaty.

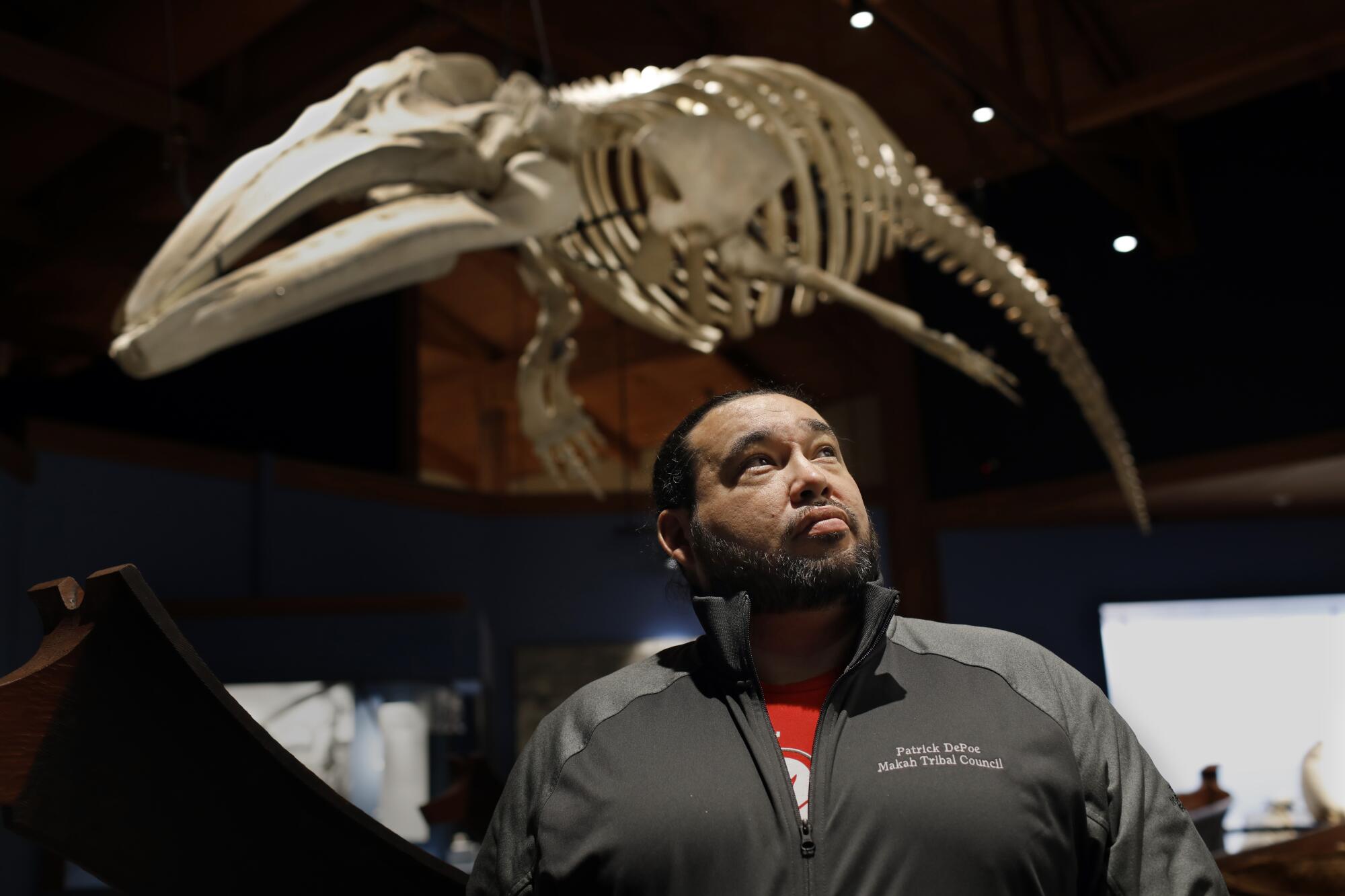

For Patrick DePoe, an aspirational whale hunter and treasurer of the Makah tribe, the law is crystal clear: “Nobody has to like it. But they do have to respect it. It’s the law.”

The trial highlights a contentious and emotional rift between those who support the rights of Native Americans to continue traditional ways of life — rights that were and are supported by law — and those who believe that in some cases, such as whale hunting, those traditional practices must be reevaluated under a modern light.

“This isn’t about subsistence. They don’t need the whales to survive,” said Margaret Owens, an activist and founder of Peninsula Citizens for the Protection of Whales, based in the Olympic Peninsula. “The whales, they live for decades, they know each other. They are sentient beings.”

Owens and her partners, Sea Shepherd Legal and the Animal Welfare Institute, are concerned mainly with the welfare of the whales. But their legal arguments target more scientific issues, including the federal government’s obligation to protect vulnerable populations of whales, such as an endangered population of gray whales in the North Pacific and a genetically distinct population of resident whales that veer east from the northward migration and feed in Puget Sound for several months. There are concerns these whales could be accidentally killed in a hunt.

They also question the government’s decision to move forward with the hunt while whales are inexplicably dying off in large numbers along the Pacific Coast. On May 31, NOAA announced it was investigating an “unusual mortality event” among gray whales. More than 214 have washed up along North America’s west coast since January.

“We don’t really know how bad it is,” said D.J. Schubert, a biologist with the Animal Welfare Institute, referring to the fact that most whales sink after they die, suggesting hundreds if not thousands more could be dead. In 1999 and 2000, after a similar die-off, the population shrank by 25%. A cause was never determined.

“The Arctic is changing rapidly. The food web has been significantly altered. That’s not going to get better,” he said. “And so, from our perspective, let’s just put this on hold. At least until NOAA determines what the causes are.”

The parties battled publicly at a trial last month in a federal building in Seattle, where Administrative Law Judge George Jordan listened to seven days of testimony from nearly two dozen scientists and activists.

Sitting in a U-shape around the judge, lawyers and experts for the federal government and the Makah faced off with attorneys and scientists for the animal welfare groups. Owens, who has been described as the “voice” of the whales, sat at the bottom of the U — across from the judge, with two official time keepers.

The parties listened to expert witnesses, cross-examined them, and often called for redirect. They engaged in sometimes-heated exchanges over the impact of the unexplained whale die-off, the genetic implications of sub-groups of whales and the impact of climate change on the Arctic.

Jordan is expected to submit a nonbinding report with his opinion to the federal government in January. After a period of public comment, NOAA will decide whether to grant the waiver and allow the Makah to apply for a hunting permit.

Hunting could begin as early as the end of next year — or be delayed indefinitely, if welfare groups challenge the waiver and permits, and bring the hunt back to court.

For the Makah, the wait has been too long.

For thousands of years, the Makah and their kin, the Nuu-chah-nulth nation — whose coastal territory spread from Neah Bay up along the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island — hunted whales for subsistence. The practice runs through their language and culture, and the tribe’s symbol, a thunderbird holding a whale in its talons, speaks to its centrality for tribal identity.

“The thunderbird brought us the whale and fed us” when the Makah were starving, DePoe said, explaining the legend behind the symbol.

The tribe voluntarily stopped hunting in the 1920s, he said, as they saw the whales being hunted to near extinction by commercial whalers.

“We have always lived sustainably and in balance with our environment,” said DePoe, walking a visitor around the Makah cultural center in Neah Bay. Pointing to various exhibits showing the tribe’s craftsmanship, boat building skills and mastery of textiles, he noted the Makah’s approach to fishing and timber, which incorporates strict limits and quotas, designed to keep the ecosystem in check.

Roughly 1,500 Makah live on the tribe’s reservation, which is situated at the end point of the Olympic Peninsula — a mountainous, rugged landscape, flanked by the Pacific Ocean on the west and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, or Salish Sea, to the north. The village of weathered homes and buildings sits adjacent to a protected harbor and the tribe’s marina.

On a recent visit, a bald eagle was seen roosting in a leafless tree along the town’s main artery, Route 112, as cars and pickup trucks slowly cruised by in the cold, dark rain.

In 1994, after a nearly seven-decade hiatus from whale hunting, gray whales were delisted from the Endangered Species Act. With their numbers surpassing sustainable levels, the Makah lobbied for the delisting and were granted permission by the United States government to hunt again. On May 17, 1999, the tribe harpooned and killed a 30-foot juvenile female.

The tribe used a combination of modern and traditional techniques. The initial harpooning was done from a canoe. When the whale was struck, more harpoons were thrown — all attached to floats — to keep the whale from diving.

A rifleman on a nearby motorized boat then shot the whale in the head with a .50-caliber armor-piercing assault rifle — providing a large enough blast to break through skull and pierce the brain. The shot was followed by a second.

The use of a gun allows for a quick, humane death, according to Allen Ingling, a retired professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Maryland, who was hired by the Makah to study quick, efficient and humane methods of killing.

According to an environmental assessment report by NOAA, Ingling and the Makah assessed a variety of weapons for “efficiency, safety, and humaneness.” They tested them in water tanks and even had an opportunity in the field: In 2010, Ingling and others fired three shots from a .577, in combination with drug injections, to euthanize a 30-foot humpback who’d stranded itself on a beach in East Hampton, N.Y.

In 1999, estimates suggest it took roughly eight minutes between the time the first harpoon hit the young whale until it died.

DePoe and his co-councilman, Nate Tyler, said traditional hunts, without the use of a rifle, often took hours or days — putting the whale through excruciating pain and fear, while endangering the lives of hunters.

“It took incredible strength and bravery,” said Tyler, who explained how hunters would sometimes dive underwater after harpooning a whale to sew its mouth shut, keeping water out of its body, and therefore afloat. The traditional sewing was not done in 1999, and the whale sank.

DePoe, who was 17 at the time of the 1999 hunt, said he remembers the excitement he felt when the older men in his tribe killed the whale, pulled it from the depths, and towed it to land.

“It brought together our community,” he said, describing the butchering on the beach and the meals and celebrations that followed.

His sentiment was echoed by Monique Villa, 36, a waitress at the Warm House restaurant in Neah Bay.

Overlooking the Makah marina, as cold winds blew in over the gray, choppy-water from the Pacific, Villa, the mother of five children, says the 1999 hunt led to a resurgence of pride in her community, and the schools now teach the Makah language and the children are excited to learn about their ancestors.

“I get chills when I remember that day,” she said.

The Makah were blocked from hunting again after activist groups accused the federal government of failing to conduct a thorough assessment under the National Environmental Policy Act. The administrative law trial that ended two weeks ago in Seattle marks the end of a nearly 20-year process by the government to legally evaluate the hunt.

But not everyone along the southern coast of the Salish Sea — the waters between the Olympic Peninsula and Vancouver Island — is excited about the potential resumption of hunting.

Owens, a curator at the Depot Museum in Joyce, a community about 50 miles east of Neah Bay, believes the hunt is unnecessary and cruel.

Sitting in the town’s old train depot, a 1915 log building built by employees of the Chicago-Milwaukee Railroad, she pointed to a map of the whales’ birthing grounds in Mexico. There, she says, the whales become accustomed to and trusting of humans from an early age; tourists touch and pet the calves, oohing and aahing as young whales approach with their mothers.

When they get to the Olympic Peninsula, and venture east into the Salish Sea to feed in the grounds their mothers and grandmothers did before them, they are not afraid of the canoes or the boats that approach.

“It’s a betrayal,” Owens said. She said she has nothing against the Makah. Rather, she deeply respects them, she said. She just doesn’t support the killing of whales.

For DePoe and Tyler, however, Owens and those who oppose the hunt are emblematic of those who have, for centuries, told them how they should behave, worship and live. And DePoe is frustrated that he has to convince anybody of his legal right to hunt.

“I shouldn’t have to explain. It’s none of their business. It’s the law,” he said.

Government scientists say the hunt, which would grant the tribe roughly 2.5 whales per year, will have an insignificant effect on Eastern Gray Whale populations, which the last census suggested is at a historically high level — about 27,000 whales.

In addition, a quota from the International Whaling Commission allows Russian and U.S. tribes to kill an average of 141 every year. The Russian Chukotka tribe has largely hunted the annual maximum quota. The two or three whales the Makah could claim would come from this quota — so their take would come from animals already targeted.

Opponents worry that whales from the western part of the Pacific, which migrate along Asia’s east coast and number about 140, could get caught in the hunt. Radio tags indicate some of these whales occasionally join the eastern Pacific whale migration from the Arctic down to Mexico.

One of the Makah’s witnesses, a geneticist who works with ExxonMobil, claims the western Pacific whales are not, in fact, a distinct group. The oil company has a facility in the western Pacific, at Sakhalin Island, where the whales are known to frequent.

In addition, some of the whales that migrate along the North American coast never reach Alaska; instead they feed in the Salish Sea and along the coast from Northern California to British Columbia. These animals are a genetically distinct population, and they too could become targeted.

It is these whales, known as Pacific Coast Feeding Group, that particularly concern Owens. These creatures hug the shores of the peninsula from the Makah’s hunting grounds at Neah Bay all the way toward Seattle.

Pointing from a vista known as Tongue Point into Crescent Bay — a stunning harbor of cliffs, white sands and rugged, rocky islets jutting from the water below — she noted where she had brought her children over the years to watch these resident whale mothers and their calves feed as they returned each spring.

“They came here for protection,” she said.

Then, as a pair of oyster catchers raced by in the sky and two harlequin ducks paddled in the water below, she turned her back to the water and climbed the stairs toward the parking area above, stopped and sighed.

“They learned it was safe here,” she said.