BOILING POINT: Will mainstream Californians quit buying gasoline cars?

Hi, I’m Russ Mitchell, a staff writer on The Times’ climate team, filling in for my colleague Sammy Roth.

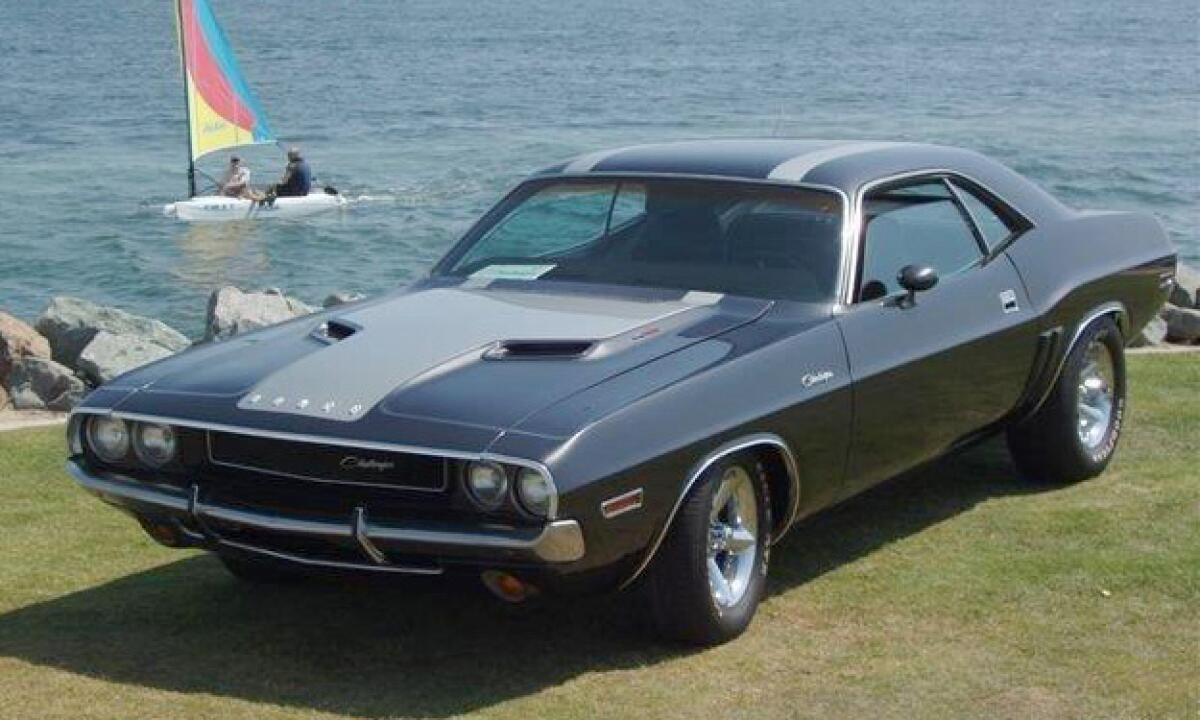

I was a teenager in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when the muscle car era was at its peak. Mustangs, Camaros, Chargers, Challengers, Road Runners, GTOs. The sound of a rumbling V8 at idle still pumps my adrenal glands. The pulse and power of gasoline engine at high rev carries a signature all its own.

Veterans of the era know what I’m talking about. “There’s a roaring fire in there!” legendary automobile executive Bob Lutz once shouted at me, 15 years ago now, as we raced around a General Motors test track in a newly remodeled Chevy Camaro. “Stuff is exploding in there! Something is happening in there! No electric motor is ever going to do that!”

He was right. Still, I’m ready to leave gasoline cars behind. The climate crisis is real. I’ve learned to love the quiet ride of an EV, the smooth operation, the convenience of charging at home, the freedom from constant maintenance, the lower cost of electricity compared to gasoline (at least for now) and the instant torque off the line that a gasoline engine cannot match.

Trouble is, the continuing lack of a reliable charging network in California keeps getting in the way.

I already drive an EV. My small family in Berkeley owns two cars: a hybrid SUV that we take to Tahoe for snowboarding and that we depend on for occasional trips to L.A., and an all-electric car we use for almost everything else.

It’s a little one, a BMW i3s we bought used for $25,000, and we love it. The range tops out at a scant 120 miles, plenty for day to day driving around the East Bay or into San Francisco. Each night, when electricity rates hit their trough, we plug it in and fill it up, ready for action in the morning.

I’d like to buy an electric car for long trips, too. But would I? No, absolutely not now. Would I suggest anyone buy an electric vehicle as their only car? Only if they never travel long distance, or if they’re willing to borrow or rent a car for the occasional distant journey.

Why? Hear my tales of woe:

Two years ago in September, I borrowed a Ford F150 Lightning electric pickup truck and drove it from Berkeley to Los Angeles down Interstate 5. The truck was great. The charging experience? Miserable. Chargers out of order. Long waits for the ones that worked. False promises about how fast a car battery could be filled.

Last month, I took the same trip, this time in the Cadillac Lyriq, the luxury brand’s all-electric crossover. That’s a nice vehicle, too. Attractive design inside and out. A smooth, quiet but powerful ride. The car’s Super Cruise system, combining adaptive cruise control with automatic lane changing, worked safely and without a hitch.

The charging experience this time around? Not much change over the past two years. Chargers out of order. Long waits for the ones that worked. False promises about how fast a car battery could be filled.

My family’s first stop was the Electrify America station at Harris Ranch, roughly halfway between San Francisco and L.A. The Lyriq’s stated range is 310 miles. If I could fill up here, I could make it the rest of the way to L.A. without another stop.

But no. These chargers, billed as “Hyperfast,” promise to deliver up to 350 kilowatts. Technically, that could take care of a late-model EV in 20 minutes. Even a rate of 150kw is acceptably speedy. But every car at this station but one had been limited to 37 kilowatts, translating into well over two hours of charging. With four or five cars waiting at any given time, the impatience was palpable, with some drivers standing with folded arms and sending out the bad eye.

We scooted well short of a fill-up and searched for another station. An Electrify America station in Kettleman City had 10 chargers. Only three were out of order! No line when we got there. But same thing: 37kw. Slow, slow charging.

Such a practice is called “throttling down.” Throttling can happen for many reasons, including too many cars charging at once at a station that can’t handle the full load. Heat can also slow a charger down.

Whatever the reason, it’s enough to turn a pleasant trip into a nerve-racking scavenger hunt for power. Those car reviews that quote automakers boasting an 80% charge in 20 minutes? Technically true. But in the real world, at a public charger? Don’t believe it.

We searched on PlugShare, the charger-finding app, which proved, like two years ago, short of reliable. It directed us to a ChargePoint station not far away with three fast chargers. According to the app, all three were working and one was open. When we got there, two cars were charging up but the third was dead. Each car had an hour to go, so we moved on.

We ended up at an Electrify America station off the Buttonwillow exit. The line at times was six cars long, and we spent way too much time at the adjacent Taco Bell. That chewed up an hour and a half. On the positive side, I got to sample my first Diet Mountain Dew at the Taco Bell soda fountain, and it’ll be my last — apologies to Tim Walz and JD Vance. The charger delivered 70kw, an unspectacular but reasonable speed. That got us to L.A.

We were visiting the UCLA campus in Westwood. Local charging was no less a hassle. To fill up in central Westwood, you pay to park in a multi-story garage, then pay EVgo a “session fee” of $2.99 just to get started, then pay 66 cents a kilowatt hour, more than double the average rate for residential electricity in California. If only the chargers delivered anywhere near their advertised speed! These 50kw “fast” chargers were throttled in half, to 25kw. It took hours to fill. I killed the time at the Ministry of Coffee, glad I’d brought my laptop.

A couple days later, at an EVgo station in a UCLA campus parking garage, I’d hoped to fill up for the trip home, I found three of six chargers out of order. It was 10 p.m. with a line of three cars. I returned to the hotel and tried again at 5:30 a.m. No line, but all stations were busy. I had to roust an Uber driver whose car was fully charged but he didn’t know that, because he was sleeping inside.

Why is the situation still so bad? Sales of electric vehicles have grown dramatically since 2022, but the number of electric chargers has not kept up, so lines of cars waiting to charge are all too common on popular routes. However, electric car sales have flattened out in recent months, and carmakers are slowing down their rollouts of electric vehicles. Surveys show that unreliable public charging is the top reason why potential customers aren’t considering an electric car. A Pew Research survey in June said 56% of U.S. adults were not too or not at all confident that the U.S. will build an adequate charging infrastructure and another 31% were only somewhat confident. (The results differed by political party. Still, only 19% of Democrats and 5% of Republicans felt very or extremely confident.)

By this point, many readers will be wondering about Tesla. Indeed, Tesla’s proprietary Supercharger system is by far the most reliable charging network. But anyone considering a Tesla must balance that out with the quality of the cars themselves, which rank 24th out of 26 on Consumer Reports’ used car reliability list. Plus, buying a Tesla means putting more money in the pockets of Elon Musk.

Speaking of Musk, he’s been promising to open up Tesla chargers to other makes and models, with a so-called Magic Dock that will allow almost any EV to use a Supercharger. He’s even recruited Gov. Gavin Newsom into his promotional campaign. The governor made a video about it in April. At the time, there were only four Supercharger stations in California equipped with Magic Docks, in and around Sacramento, where the politicians reside. To date, there are still only four.

Beyond the scarce Magic Dock, non-Tesla drivers can pay $200 for an adapter that will work at many Supercharger stations. Some carmakers, including Ford, will hand them out free with an EV purchase. And most of the auto companies are planning to design future models to accept Supercharger plugs.

What role has the state played in all this? The agencies that dole out state money to public charger companies — the California Energy Commission and the California Public Utilities Commission — have taken a soft-core approach to holding the companies responsible. The state insists on 97% guaranteed uptime in return for the government funding, but the bureaucracy hasn’t yet defined what 97% uptime means. Some charger companies’ executives, meantime, have grown rich with state support, doing equity deals and buying fancy houses, even as their companies failed to perform and lost money.

Newsom had decreed that more than 50% of new vehicles sold in 2028 must be electric, and 100% by 2035. Right now, the figure is near 25% (plug-in hybrids included). A recent survey by consulting firm McKinsey showed that 38% of current EV owners in the U.S. plan to eventually replace their EV with a gasoline or diesel car. If EV mandates can’t be reached, the state government itself deserves a large share of the blame.

We’ll be back in your inbox on Thursday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. For more climate and environment news, follow Sammy on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.