Ukraine is a climate story. Because everything is a climate story

This is the March 3, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

You know that scene in “The Matrix” where Keanu Reeves is offered a choice between ignorance and truth, in the form of a blue pill and a red pill? If he takes the blue pill, he’ll forget the unsettling reality he’s begun to uncover, and go on living his life like everything is fine. But if he takes the red pill, he’ll learn the truth about the world — and he’ll never be able to unlearn it.

Well, paying attention to climate change is like taking the red pill. Once you do, nothing will ever look the same.

The weather, a hike, a trip to the grocery store — you might start seeing it all through a climate lens. Should the Super Bowl really be this hot? How much of this trail is still recovering from the latest wildfire? How often should I be eating meat?

I took the red pill a long time ago. So with Russia laying siege to Ukraine, I wrote about the climate implications. Because of course there are climate implications. Europe is heavily dependent on Russian oil and gas, and security experts told me accelerating the global transition away from fossil fuels — and toward clean energy — could help limit Vladimir Putin’s geopolitical influence.

“There’s been a lot of concern about dependence on Russian [natural] gas, and whether that inhibits countries’ ability to stand up to Russia,” said Erin Sikorsky, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Climate and Security. “The more that countries can wean themselves off oil and gas and move toward renewables, the more independence they have in terms of action.”

A few days later, as missiles flew over Ukraine, the United Nations dropped a different kind of bombshell.

The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a landmark report finding that more than 3 billion people are highly vulnerable to rising global temperatures, and that heat-trapping emissions continue to increase even as the crisis deepens. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called the report “an atlas of human suffering,” my colleague Ian James reports.

“The world’s biggest polluters are guilty of arson of our only home,” Guterres said.

The United States is the biggest polluter of all, responsible for about 25% of historical carbon emissions. Russia isn’t far down the list, contributing 6% of cumulative global emissions. Putin, though, has often seemed more focused on the potential benefits to Russia of melting Arctic sea ice opening up new shipping routes. And while President Biden has pledged steep cuts to carbon emissions, his most ambitious climate plans have been blocked by congressional Republicans — and at least one Democrat.

The war in Ukraine offers American and European leaders an opportunity to advance clean energy while combating Putin — and at least some of them are taking advantage of it. European Union officials are finalizing a strategy to slash the continent’s use of natural gas, in part by accelerating deployment of solar power, renewable hydrogen and energy efficiency.

But as is too often the case, short-term political expedience may prevail over the climate imperative.

With gasoline prices rising in part due to Russian aggression — the country is a major oil exporter — Biden said in his State of the Union address this week that the U.S. will release 30 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, as part of a coordinated plan among America and its allies to keep gasoline prices steady. Those oil releases aren’t going to make or break international climate efforts. But Biden discussed the urgency of climate action only briefly during his State of the Union.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and Europe have declined to cut off the flow of Russian oil and natural gas, despite hitting Putin with other sanctions. The Biden administration is worried about causing gasoline prices to rise further, my colleague Don Lee reports.

Conservative politicians and the fossil fuel industry want to see Biden take longer-term steps to boost U.S. oil and gas, such as approving export terminals and leasing more federal lands for extraction. Sen. Roger Marshall, a Kansas Republican, urged Biden this week “to restart America’s energy production.” Mike Sommers, chief executive of the America Petroleum Institute, an industry trade group, wrote, “At a time of geopolitical strife, America should deploy its ample energy abundance — not restrict it.”

That’s one option — but according to energy experts, it would lock in dependence on fossil fuels that humanity can’t afford.

Another option is ramping up investments in solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, electric cars, electric heat pumps, green hydrogen and other clean-energy technologies. Modeling released last year by the research firm Energy Innovation found that cutting U.S. emissions in half by decade’s end — which scientists say is needed to avoid truly catastrophic warming — would grow the economy by $570 billion annually by 2030, and avoid 45,000 premature deaths through reduced air pollution.

President Biden’s Build Back Better Act — which is stalled in the Senate — would go a long way toward helping America meet that emissions goal, according to a new report from the REPEAT Project, which is led by Princeton University researchers. The bill would also reduce household energy costs by $300 per year on average and drive a net increase of 2 million jobs, researchers found.

And let’s not forget the geopolitical benefits, which are front of mind following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“We also need to be thinking about the new world order that we are now living in. Everything has changed,” Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton energy engineer, said in a webinar on the REPEAT Project report. “The United States has a considerable opportunity to reshape the global energy landscape with the kinds of investments that are in the Build Back Better Act.”

“We can’t just put a Band-Aid on things and move on,” Jenkins added. “We really need to deeply think about how to restructure the global energy system to avoid this kind of exposure to the whims of a single country, or a single man.”

There’s a reason American military leaders have been taking climate seriously for years. The Pentagon first called global warming a “threat multiplier” in 2014, later warning that the climate crisis “will have wide-ranging implications for U.S. national security interests over the foreseeable future because it will aggravate existing problems — such as poverty, social tensions, environmental degradation, ineffectual leadership, and weak political institutions — that threaten domestic stability in a number of countries.”

All of which gets at my main point, which is that climate change touches every aspect of modern life — as does the urgent need to stop polluting. Wildfire, war, energy, drought, heat, floods, migration, pandemics, asthma, wildlife, housing, coastlines, rivers, crops, meat, freeways, supply chains, air travel, trash, plastics — climate story after climate story after climate story.

And if Ukrainian leaders have their way, the planet’s biggest polluters will keep those stories at the top of their agendas.

During the Glasgow climate summit last fall, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky wrote that it is “the moral duty of wealthy countries to help developing ones ensure green modernization of their economies.” If humanity fails to slow the pace of climate change, he wrote, “after 2030 the social and economic losses will be so significant that we simply can’t even imagine it.”

Even last week, as Russian forces attacked, Ukraine sent delegates to a U.N. meeting to finalize the new global climate report. The discussions were closed to the public. But the Washington Post’s Sarah Kaplan reports that Ukrainian scientist Svitlana Krakovska declared that the climate crisis and the Russian invasion “have the same roots — fossil fuels, and our dependence on them.”

“We will not surrender in Ukraine. And we hope the world will not surrender in building a climate-resilient future,” she said.

It’s a powerful message — about as powerful as it gets.

While we wait to find out if the world listens, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California just had its driest January and February on record, meaning we’re likely entering a third year of drought. Here’s the story from my colleague Hayley Smith, who writes that snowpack is at 63% of average, the state’s largest reservoir is at 37% of average and Sacramento has gone nearly two months without rain. Some of the worst impacts are in the Central Valley, with The Times’ Ian James reporting that California farmers left 395,000 acres unplanted last year, resulting in nearly 9,000 lost jobs. Many agricultural operations served by the federal Central Valley Project are set to receive no water whatsoever this year, Ian reports.

Speaking of the Central Valley, Fresno County supervisors rejected a $175,000 state grant to study the impacts of climate change on vulnerable rural communities. Why turn down money to help the vulnerable? In part because supervisors worried they’d be working with researchers who are anti-agriculture, per Melissa Montalvo at the Fresno Bee. For another illuminating Central Valley tale, check out this gorgeous and haunting story by The Times’ Diana Marcum — with illustrations by Paul Duginski — on the “darkly enchanting” return of tule fog after years of absence. Climate change may be to thank — or to blame.

Why has FEMA denied aid to low-income residents of Grizzly Flats, Calif., whose homes were destroyed by the Caldor fire? My colleague Alex Wigglesworth talked with families who haven’t been able to rebuild and explained why the Federal Emergency Management Agency claims its hands are tied. Critics say FEMA’s programs are geared more toward floods and hurricanes, and less toward climate-fueled fires — which aren’t just a problem in the American West, by the way. A new United Nations report finds blazes are getting worse around the world, Hayley Smith reports. Hayley also has a story on new regulations proposed by California officials that would require insurance providers to offer lower rates to people who harden their homes against wildfire.

FOSSIL FUEL POLLUTION

It’s hard for me to imagine what life must be like with 18-wheeler trucks rumbling down your street, spewing diesel fumes and kicking up dust day and night. But The Times’ Thomas Curwen and Carolyn Cole paint a powerful picture in this stunning piece on Drumm Avenue in Wilmington, near the ports of L.A. and Long Beach. Trucks use the street to get to a shipping container storage depot, and some companies are piling those containers high near homes and violating local rules, Thomas reports. This is a textbook case of environmental injustice, in which low-income communities and people of color bear the brunt of pollution.

A new report out of USC finds that California communities with more people of color and low-income homes have been less likely to see reductions in pollution. Some activists say it’s the latest evidence that cap and trade — a state program meant to reduce planet-warming emissions — isn’t working for the most vulnerable, Kristoffer Tigue writes for Inside Climate News. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration is counting on cap and trade to achieve a large share of the emissions reductions needed by 2030, but a state advisory board is not optimistic the market-based program can get the job done, the AP’s Kathleen Ronayne reports.

The company whose undersea oil pipeline ruptured in October is suing the owner of two cargo ships that it says dragged the pipeline with their anchors, paving the way for the Orange County oil spill. Details here from The Times’ Laura J. Nelson and Connor Sheets. Speaking of ocean pollution, James Rainey reports that California is now the first state with a comprehensive plan to stop flushing so many microplastics into the ocean, although much of the plan still needs approval from lawmakers or regulatory agencies. Elsewhere along the coast, my colleagues Priscella Vega and Matt Szabo report that Poseidon Water asked state officials for a two-month delay of a hearing seeking approval to build a seawater desalination plant in Huntington Beach.

AROUND THE WEST

A rare daisy only grows in two remote spots in the Inyo Mountains near Death Valley National Park — and conservationists want to see it protected under the Endangered Species Act, in part to block a planned gold mine. Here’s the story from The Times’ Louis Sahagún, who hiked through the daisy’s habitat with botanists and writes that climate change is taking a toll on desert ecology. K2 Gold Corp. has begun drilling and trenching on public lands in advance of building a large open pit mine.

In 2007, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation thought there was less than a 10% chance of Lake Powell falling below 3,570 feet by 2050. Well, the nation’s second-largest reservoir got there last March and kept dropping, Zak Podmore reports for the Salt Lake Tribune. And still today, 15 years after that failed forecast, researchers say the Bureau of Reclamation continues to underestimate how much Lake Powell will fall as climate change saps Western waterways, the Colorado Sun’s Chris Outcalt writes. Underscoring the increasingly dire situation, a federal official says the reservoir is likely to dip below a critical level in the next two weeks.

Another 9.5 million trees died in California last year — not counting the ones killed by wildfire — as drought makes them more vulnerable to disease and infestation. That’s 172 million dead trees since 2010, Kurtis Alexander reports for the San Francisco Chronicle — again, before we even get to blazes such as the Dixie fire, which is estimated to have killed 100 million trees. Researchers say California must do more to clear vegetation and thin out its forests after a century of aggressive fire suppression.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

The governors of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — two Democrats, two Republicans — want to form a joint “hydrogen hub” and apply for a share of $8 billion in federal funding. Hydrogen could serve as a clean-burning fuel to help replace oil and gas, but it’s controversial among some environmentalists. Here’s the story on the four-state collaboration from the AP’s Mead Gruver, and more details from the Colorado Sun’s Michael Booth. In another story about a controversial fuel, Janet Wilson and Joshua Yeager report for the Visalia Times-Delta that Amazon, Chevron and other firms are collectively pouring billions of dollars into cow poop, with subsidies from California. But is biogas a crucial climate solution, or a boondoggle for big polluters?

Berkshire Hathaway Energy says it will cut its carbon emissions in half by 2030, and shut down all its natural gas plants by 2050. Those are significant commitments from Warren Buffett’s firm, as reported by Bloomberg’s Katherine Chiglinsky. But will the federal government be able to require Berkshire and other energy companies to cut down on climate pollution? The Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, heard a case this week that could severely restrict the federal government’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, as Robert Barnes and Dino Grandoni write for the Washington Post. The outcome is not certain, though. It sounds like conservative justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett suggested the Environmental Protection Agency may have the authority to regulate carbon emissions, per Bloomberg’s Greg Stohr and Jennifer A. Dlouhy.

California electricity rates are rising, and they’re expected to keep rising in the coming decades. What can the state do to keep energy bills affordable? Some utility companies and government officials told the California Public Utilities Commission the state should stop funding “public purpose programs” — such as energy efficiency and wildfire prevention — through utility customer bills, and start paying for them out of the general fund instead, Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

ONE MORE THING

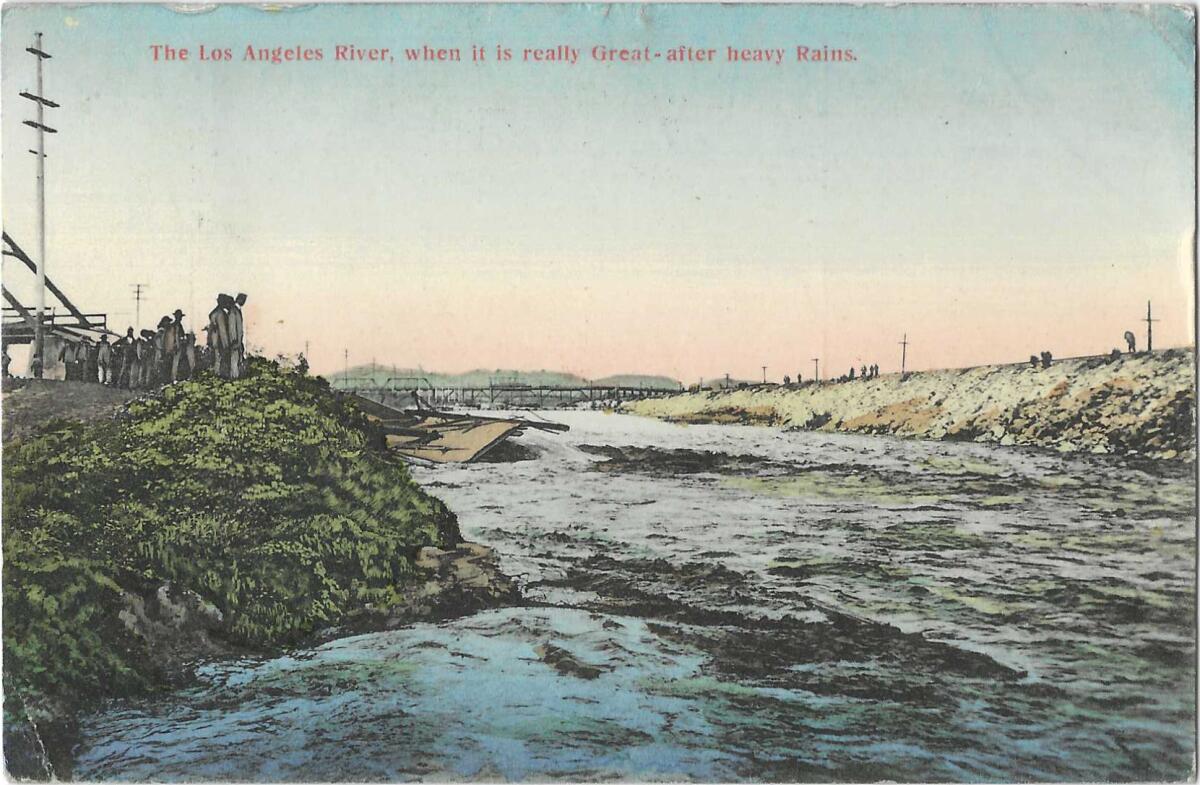

If you’ve got any interest in the Los Angeles River, check out this column by The Times’ Patt Morrison. Patt thoughtfully traces the river’s history from concrete encasement to Hollywood stardom, to the complications of “restoring” the waterway today.

“Now that there may be ribbons for politicians to cut with giant scissors and names to be credited on dedicatory plaques — now that everyone wants a piece of the orphaned river, there aren’t enough pieces to go around, to satisfy every interest and demand: environmental, natural, recreational, residential, drought-minded,” she writes. “From an actual, living river, how did we get here?”

It’s a tough question to answer — but the interesting ones almost always are.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.