The Coens’ ‘Inside Llewyn Davis’ aims to keep 1960s folk scene real

- Share via

NEW YORK — A single song bookends “Inside Llewyn Davis,” the forthcoming film from Joel and Ethan Coen about a week in the life of a struggling singer in the New York folk scene of the early 1960s. It’s a gentle guitar ballad starring a dangling noose called “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” and its best-known version is by the late Dave Van Ronk, a towering singer whose recollections of Greenwich Village during the folk boom informed the narrative.

In its opening scene, the movie focuses on the song as performed by the titular Davis, played by actor and musician Oscar Isaac. Shot in intimate close-up as he sings and picks on an acoustic guitar in a Village coffeehouse, the rendition introduces the character through lyrics about a man staring across an abyss.

“Hang me, oh hang me, and I’ll be dead and gone,” sings Davis, repeating the phrase for emphasis before deciding he’s too restless for death. “Wouldn’t mind the hanging, but the laying in the grave so long/ Poor boy, I’ve been all around this world.” The story’s closing scene offers another angle on the song, also performed by Davis, but with an added layer of meaning based on the curious story the filmmakers have just told.

PHOTOS: Holiday movie sneaks 2013

That story touches on many angles in the life of the artist, addressing the power and perils of reinvention, the lure of commercialism and the oft tense issues of class and race — in this case the college-educated instrumentalists and the rural, more “authentic” voices of the South. Perhaps uncoincidentally, the film comes at a time when a number of young folk groups such as Mumford & Sons, the Lumineers, the Punch Brothers and the Carolina Chocolate Drops have resurrected the music’s many varietals for fresh consumption — and dented a marketplace crowded with beat-heavy, compressed dance pop and hip-hop acts making tracks on hard drives.

The film’s soundtrack arrives Monday in advance of the “Inside Llewyn Davis” release on Dec. 6. Produced by T Bone Burnett, who collaborated with the Coens throughout the process of casting and recording, the record is filled with cleanly recorded traditional music set to tape in midtown Manhattan. It’s performed both in the film and on the soundtrack by the cast, which includes Isaac, Justin Timberlake, Carey Mulligan (part of a Peter, Paul & Mary-suggestive duo with Timberlake) and, in a memorable backing vocal scene, Adam Driver. Burnett’s soundtrack and the score also feature Chris Thile and fellow members of the Punch Brothers along with Marcus Mumford, Stark Sands and others.

In spirit, the approach resembles that of an earlier Coen brothers and Burnett collaboration, the 2000 “O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” which focused on American rural music of the 1930s.

RELATED: Best albums of 2013 so far | Randall Roberts

“Davis” revisits the quaint cultural world centered long ago on MacDougal and Bleecker streets, the echoes of which helped define American acoustic music over the following decades.

It’s a period in which singers including Van Ronk, the New Lost City Ramblers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Tom Paxton, Fred Neil, Peter, Paul & Mary and others shed their past to build a thriving music culture centered on Sunday afternoons at Washington Square Park and a passion for Woody Guthrie, the Carter Family, country blues 78s and Harry Smith’s “The Anthology of American Folk Music.”

They were in a sense early American crate-diggers: music fans who, like their 21st century kin, scoured shops for strange records then shared them among their friends — the difference being that instead of remixing or file-transferring them the musicians swapped by learning and playing, in the process adapting the music to fit their voices. And that’s one of the special appeals of this kind of reimagining — it shows a period at once far removed from and familiar to younger listeners.

Such adaptation and reinvention continued in September when, as they did with “O Brother,” the Coens and Burnett teamed to organize a star-studded tribute to the music before its release. Featuring performances at Town Hall by Joan Baez, Patti Smith, Elvis Costello, Jack White and many of the film’s cast members, the show confirmed the wonderful elasticity of the music. That it was held at Town Hall, a stage where Bob Dylan gave a performance that earned him his first New York Times rave, added to the weight.

Ironically though, had this event occurred in the early 1960s, Davis the artist might have been passed over for the more earnest sounds of Peter, Paul & Mary or the Kingston Trio. Though packed with talent, the gig illustrated the continued challenge of defining so-called “real” folk music for a populace hungry for a striking face and a good love song.

An event booked to promote a major motion picture featuring established singers, many of whom have monied management and record for big-time labels, it held a stage full of talented winners in the lottery of success. By definition this was something for the locked-out workingman singer to sneer at — establishment folk — while preaching the value of the raw stuff. Such distinctions never fade: What happens to the underdog folkie when she wins? Is her voice automatically suspect when she hires a big-time producer? Must the lovely art of harpist Joanna Newsom be reassessed based on the knowledge that she’s now married to a sitcom star?

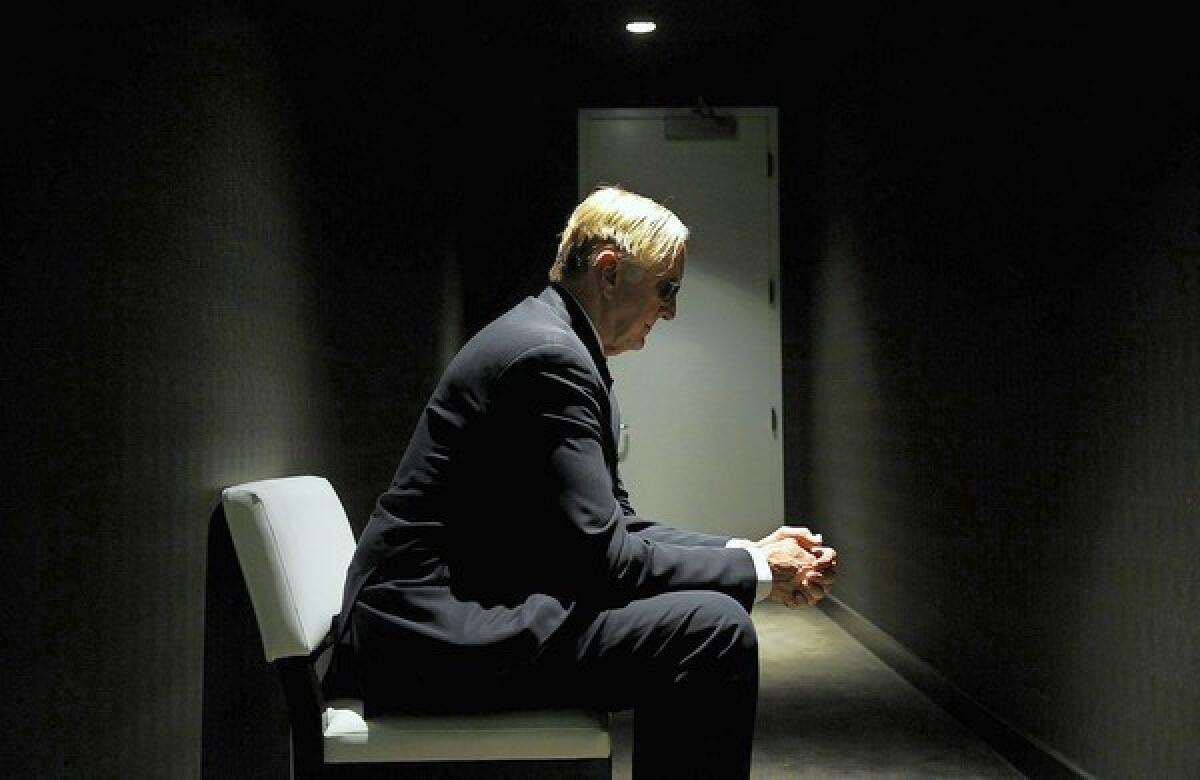

The actor Isaac, for example, is a Juilliard-trained talent with an impressive résumé whose vocal teacher has worked with famous actors — certainly not an unwashed, Will Oldham-style folkie. Not that it mattered at Town Hall, where Isaac was a standout and exuded a charisma that Burnett immediately sensed in his audition. “I’ve sat around in rooms with the best singers and writers and musicians playing music all night long,” he said in a midtown hotel in late September, a day after the Town Hall show. “At this point I’m 65 and have been doing it 50 years. I know who’s good right away. It’s not a mystery or anything.”

Burnett is well acquainted with Davis’ artistic plight. “I lived that arc two or three times — and we all do, that’s the thing,” said Burnett. “Vince Gill got dropped — I hate that word — but there was a time when he didn’t have a label, and he’s one of our greatest artists. Everybody goes through it. Everybody falls out of favor, or their champion at the company is gone and nobody wants to take a chance.”

That the artist at the center of the film must come off as strikingly talented was one of the great challenges of casting, said Burnett, a hurdle that Joel Coen confirmed during a post-screening discussion of “Davis” at the New York Film Festival. “We needed to find someone who could not only convince the audience that he was a musician,” said Coen, “but that he was a very good musician. So we’re very lucky that we found Oscar. The ambition at the beginning was that the character be transparently good at what he does.”

PHOTOS: Behind the scenes of movies and TV

Isaac, a Guatemalan Cuban American, said that by the time he tried out, they’d already tested many others. He didn’t realize the level of talent he was facing, though, until he saw a still of a musician he admires on a wall of the audition room and mentioned it to the casting director. “I saw this photograph of a guy with a beard and dark hair and said, ‘Oh, good, so you guys are using that as a reference?’ And she was like, ‘Oh, no, he just came in. He killed it.’”

By the time Burnett saw Isaac’s audition of the song “Hang Me,” in fact, he and the Coens had despaired of ever finding the right actor. Isaac walked in wearing a droopy hat that hung low on his head. “You could only see part of his face, and he started singing that song,” recalled Burnett. “He was so good. I was thinking, ‘Man, this cat is singing this song.’”

You could hear the thrill at Town Hall where, standing before a vintage condenser mike, Isaac played “Hang Me” and “Green, Green, Rocky Road” to a sold-out crowd. The concert, set to air on Showtime in December, features the musical setlist of “Inside Llewyn Davis” and many other songs. It was hosted by John Goodman, who plays a memorable character inspired by New Orleans pianist-songwriter Dr. John.

For many at Town Hall, a longtime home to New York’s folk scene, the songs were quite familiar, including Hedy West’s “500 Miles,” the traditional “Fare Thee Well (Dink’s Song)” and A.P. Carter’s “The Storms are On the Ocean.” But as is often the case with the work of the Coen brothers, just as much information is simmering below as on the surface. There’s a reason many of the songs are performed in their entirety in the film: to allow the lyrics to blossom. Like a Greek chorus, said Burnett, the musical choices within “Davis” offer a meta-narrative as the events unfold on-screen.

“There’s a distinct story being told in the libretto, really,” Burnett said. He cited as an example the old ballad “The Death of Queen Jane,” which the oft-self-defeating Davis sings to a Chicago manager based on Dylan’s real-life financial enforcer, Albert Grossman. “He goes to his big audition and he sings a song about an abortion,” said Burnett, laughing at the thought.

This being a Coen brothers script, things don’t go as planned for Davis while auditioning, and soon he’s back working the same gigs and looking for a way out. Anyone who’s tried earning a living in the arts will likely understand, added Burnett: “We just wanted it all to be real. Just like last night — no tricks up there.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.