Local indie-pop singer Miya Folick is walking fine lines and finding her voice

- Share via

“I don’t think I’m unusual in the fact that I find joy in struggle,” says singer-songwriter Miya Folick with a carefree laugh in an Echo Park cafe.

She’s been frequenting these coffee spots for the past four years between writing multiple EPs. Her alternative-pop debut, “Premonitions,” arrived last October. Coffee is one of Folick’s delights.

“It’s stressful to be alive,” she says, always with a lightness in her tone. “I used to go out, know people, see music. When I started work on the record, that was fun, but it didn’t bring me joy.”

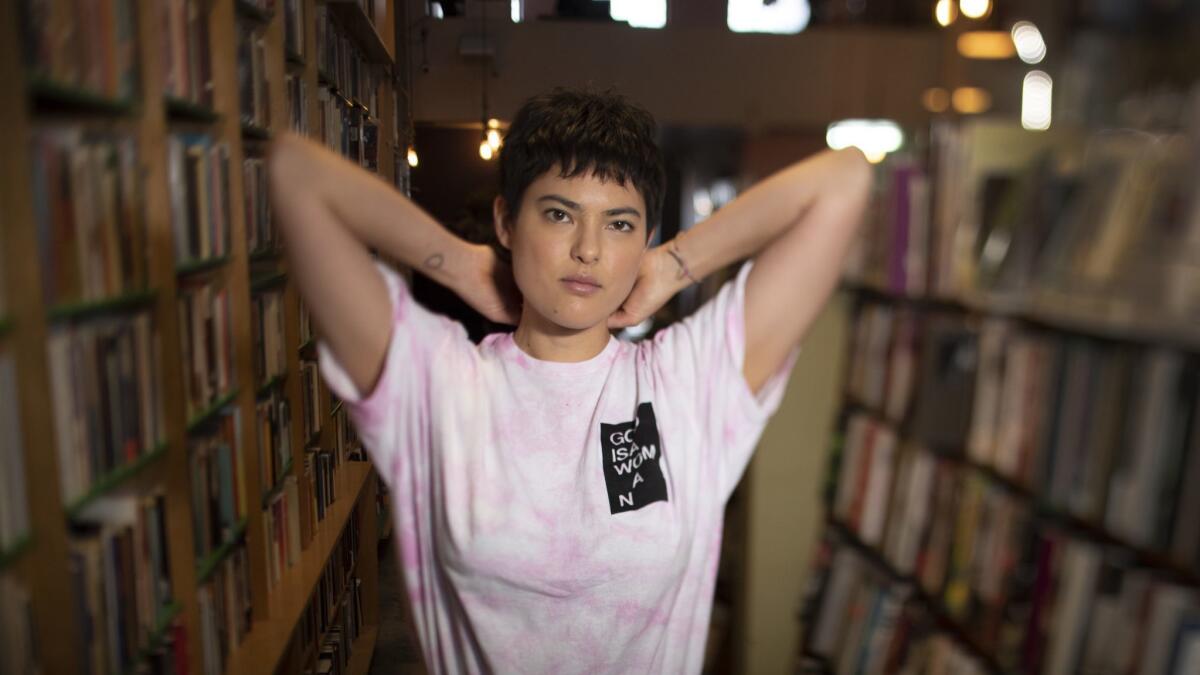

Folick is now understanding what does: early rising, walking through the city, being alone. “I’ve been tie-dyeing a lot,” she says. “I’m obsessed. I do it in a bucket in my girlfriend’s sink. It’s so relaxing.”

Today, Folick sports her own tie-dye shirt with the all-caps words “God is a woman.” It’s the title of her 2016 single, which preceded Ariana Grande’s smash of the same name. Both songs deify the female self, but while Grande uses hers to lure a mate, Folick’s lyrics are a note-to-self about recovery and survival. In every way, she’s at the other end of “pop” — “Premonitions” was produced with Justin Raisen (Charli XCX, Sky Ferreira) because she referenced Bjork’s adventurous and experimental second album “Post” to him and he wasn’t intimidated.

Folick, 28, hails from Santa Ana — the daughter of a Japanese mother and Russian father (her face appears sandwiched between theirs on the LP’s artwork — a gleeful display of genealogy). She discovered Bjork’s “It’s Oh So Quiet” at 16 and performed it at her school’s variety show. “It contains all of human emotion: stillness, excitement, anger, frustration,” she says.

Back then, Folick was a theater kid. She went to NYU to study acting but found herself caring less about auditions when she relocated to L.A. She’d dabbled in songwriting on the side, and began to dedicate more time to it, hiring a band via the dating app Tinder because she didn’t know anyone in the L.A. music scene.

There have been moments of despair, hopelessness, feeling lost. But I was searching for something. That’s my process.

— Miya Folick

Whenever pressured to define an aesthetic or a sound, she struggled. “Post” reassured her. “What is the genre of that album?” she asks. “Is it a dance album with a big-band jazz song? I don’t know. Nobody knows.”

“Premonitions” isn’t couched in one genre. The funereal stomp of the single “Deadbody” is a bridge between her grungier EPs and the electronic thrum of these panoramic songs. Folick has battled in herself to find a vision, and to navigate the industry.

“There have been moments of despair, hopelessness, feeling lost,” she says. “But I was searching for something. That’s my process.”

The LP is autobiographical working proof of that. A good studio day is one in which she channels an answer. “Trying to ‘make it’ feels like too much pressure,” she says. “I’m just trying to find it. It’s out there.”

The songs are like cushions on a bed of nails, founded in hardship and brutality, but catching the listener in their emphatic arms. They’re a house for Folick’s overpowering voice too. That’s an instrument she’s learning to wield. She grew up singing.

“I was a good student. I tried my best to sing correctly in a healthy manner with a nice tone,” she says. She’d attend gigs, and specifically recalls watching L.A. punks FIDLAR and wanting a scream of her own. “I’d try to do it in my room, and it sounded horrible,” she says. “Learning how to scream in your bedroom is very difficult.”

From Alanis Morrissette and the late Dolores O’Riordan of the Cranberries to Joni Mitchell, Folick sees her voice as a tool for guttural, primal sounds. “People perceive those vocalists as affected. They’re making sounds that are natural to them. I can whisper; I can yell; I can do these different things.”

One downside: It’s difficult to repeatedly perform. “It’s easy on a good day but 20 days in?”

The triumphant “Deadbody” is the hardest, technically and emotionally. After its release, it was dubbed a “feminist revenge song,” which infuriated Folick, as it’s not fueled by revenge.

“I wanted to set a boundary in order to make the album feel universal, but I don’t know if that was the right decision,” she says now of her reticence to explain lyrics. “Maybe I wasn’t ready, and now I’m more open.”

Her philosophy about the relationship between fan and artist recall those of indie-pop artist Mitski, so it’s fitting when Folick raises the alternative star as an example of someone who fosters a complex but safe fan environment. Folick too pours the personal into her art and doesn’t invite a free-flowing dialogue after.

I work with a lot of men who said, ‘This song doesn’t quite do it for me.’ And I said, ‘Well that song’s not for you.’

— Miya Folick

But she does intend her songs to reach particular communities. That’s why she fought for “Deadbody” — a song about taking control — which she’s been told has inspired certain fans to stand up to their bosses or leave their partners. “I work with a lot of men who said, ‘This song doesn’t quite do it for me.’ And I said, ‘Well that song’s not for you.’ ”

This care-taking bent leaves her little room for ego. “There’s a fine line between being an entertainer and being a professional manipulator,” she says. “I’m never gonna incite anger or make music that’s so about sadness.”

Folick’s songs pivot between pleasure and solemnity in a way that’s realistic. “I’m incapable of having absolute thoughts,” she says. “It drives me insane. I’m always equivocating. I’m a Gemini!”

Her biggest fear is not of bouts of sadness or happiness but of plateau. “I’m not good at feeling positive about static. Things happen so fast in the news and in culture, but people’s lives are happening just as slowly. That tension creates impatience.”

Folick is not kind to herself there, but she enjoys writing new songs. “I’m obsessed with my next record,” she says. “And actively worried about it.”

You could say Folick is a pragmatist. Her songs are self-fulfilling prophecies. Premonitions don’t always present optimism, but they tell you what’s coming.

“Sometimes my songs are a surrogate for doing a thing in real life,” she says. “I still haven’t taken care of some of them. It’s a to-do list. A to-do list sounds manageable.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Miya Folick

When: 8 p.m. Friday

Where: The Lodge Room, 104 N. Ave 56, Highland Park

Tickets: $15

Info: miyafolick.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.