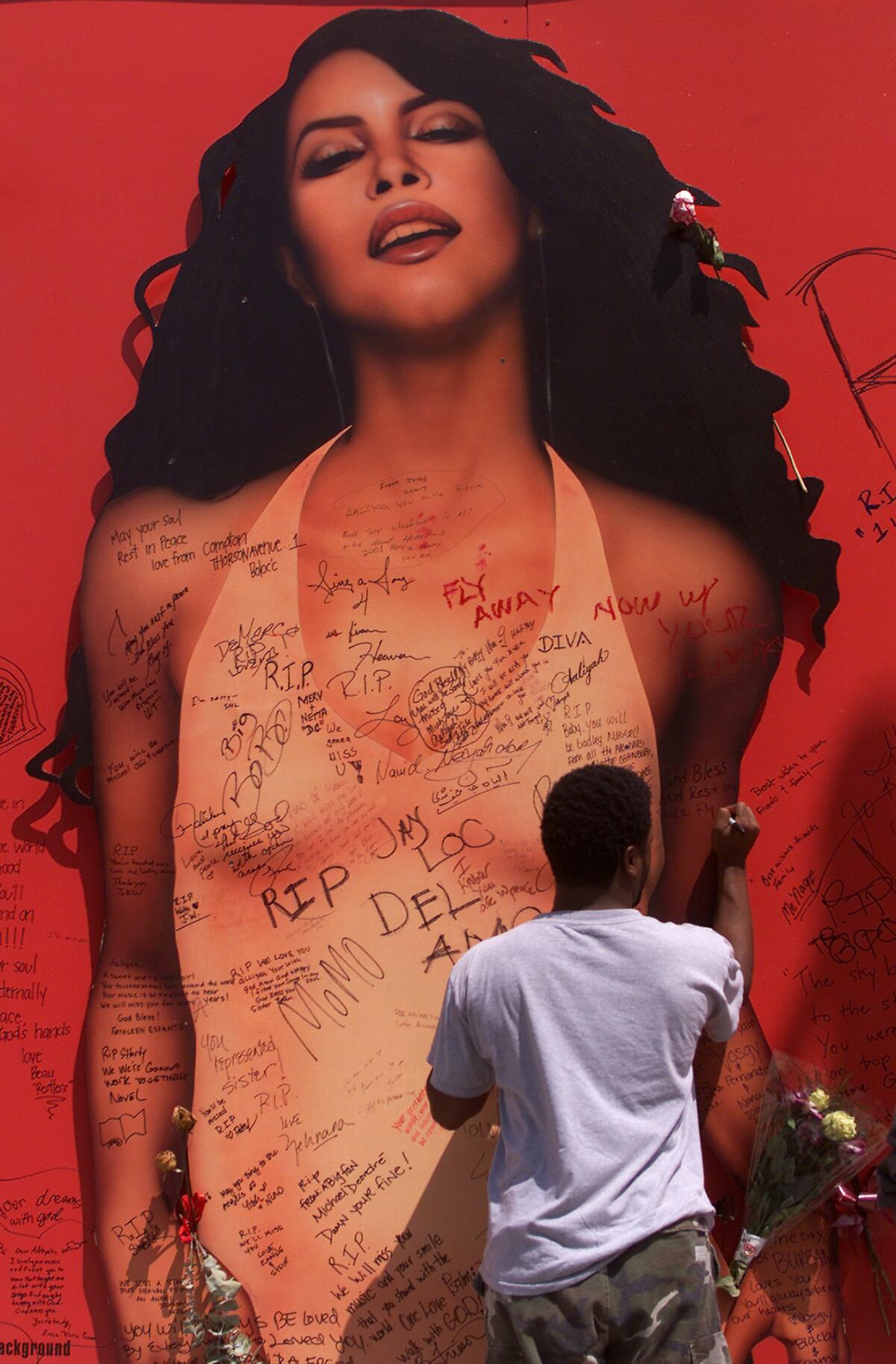

The arrival (and disappearance) of Aaliyah’s greatest hits collection is the latest in saga of late singer’s catalog

More than 15 years after her death, Aaliyah’s presence can still be felt as her influence percolates through a new generation of artists — Tinashe, Banks, SZA and Jhené Aiko are just some of today’s acts that can be traced to her.

Such an impact is impressive given her modest output — a catalog that remains largely inaccessible via today’s online outlets.

Since the advent of digital music, fans of streaming and download services have ruminated about the unavailability of the beloved R&B chameleon’s back catalog. Frustrations have increased as time has gone on.

Adding to the furor? Posthumous releases from Aaliyah’s estate have been nearly nonexistent in the years since she died in 2001, despite the believed presence of unreleased material.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

But that void appeared to close earlier this week when an old collection of the singer’s hits popped up on iTunes and Apple Music without warning.

Originally released in 2005, “Ultimate Aaliyah” paired well-known hits such as “Back & Forth,” “One in a Million,” “Try Again” and “Rock the Boat” with deep cuts from soundtracks and guest appearances. The retrospective first arrived as a three-disc set (two CDs and a DVD of music videos and assembled footage) and was issued in the UK, Australia and Japan, with pricey imported versions popping up at secondhand music retailers.

On Wednesday “Ultimate Aaliyah” was available for purchase and streaming through Apple, sending fans into a tizzy that a breadth of her well-known work was finally available for digital consumption.

However, less than 24 hours later, the music was gone.

The short-lived availability of the hits collection is the latest entry in the ongoing drama of how the singer’s work has been managed since her untimely death.

The recent release of “Ultimate Aaliyah” was the handiwork of Craze Productions, a London-based company that has issued the singer’s music digitally, albeit allegedly illegally. Details as to how the company got its hands on the music remain unclear.

This isn’t the first time Craze has come under fire.

In 2013, Aaliyah’s publisher Reservoir Media Management filed suit with Craze after it uploaded her most famous records, her final release and her groundbreaking 1996 effort, “One in a Million,” to iTunes.

Craze didn’t return a request for comment.

When the artist born Aaliyah Dana Haughton died in a 2001 plane crash in the Bahamas, she left behind a brief discography — just three albums and a handful of guest appearances and contributions to film soundtracks.

At the time, Aaliyah was in the midst of a breakout year. She had issued what became her final record, a self-titled release being lauded by critics, and was emerging as a budding film star.

After her death, executives at her label, Blackground Records, told The Times that she had “recorded enough material for at least one more album” and in 2002 the label released “I Care 4 U,” which packaged her greatest hits with six previously unreleased songs.

And then nothing else happened.

The premature death of an entertainer always brings curiosity over unreleased work, and Aaliyah was no different. Releasing that archived work — be it shelved or incomplete recordings fleshed out by producers — can often be complicated and divisive. Aaliyah’s case has proved more confounding considering the head of her label is a relative, her uncle Barry Hankerson.

“It’s weird and frustrating … I don’t think we’ll ever hear anything,” a former Virgin Records employee who worked closely with the singer told The Times for a retrospective piece marking the 10-year anniversary of the singer’s death. (Virgin was once Blackground’s distributor.)

The employee, who requested anonymity out of fear of legal retribution from the label, as well as others with knowledge of Blackground’s business dealings, all point to Hankerson as the reason behind the lack of reissues of her back catalog. Hankerson has largely kept a low profile since Aaliyah’s death and attempts to reach him were unsuccessful.

Aaliyah fans have long had complicated feelings toward Hankerson. He famously guided his niece to stardom in the early ’90s as her manager and co-founder of Blackground, pairing her with his most high-profile client at the time, R. Kelly.

R&B hitmaker Kelly helmed the entirety of Aaliyah’s 1994 debut, “Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number,” and under his guidance her brand of “street but sweet” R&B, breathy falsetto and tomboyish silhouettes saw her crowned as the “Princess of R&B.” But her career was nearly eclipsed by scandal after it was revealed by Vibe Magazine that Kelly and his 15-year-old protégée had eloped, falsifying her age as 18, as evidenced by court documents.

The union was swiftly annulled and Aaliyah went on to create important work with Missy Elliott and Timbaland — music that reinvented the sound of ’90s urban music. Hankerson, meanwhile, continued to manage Kelly for a number of years, and Aaliyah’s parents stepped in to coach her career. The scandal sullied Aaliyah’s debut and still follows Kelly, who was acquitted in 2008 of child pornography charges and settled allegations of sex with minors out of court.

Controversy aside, “Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number” remains the only body of work from Aaliyah available for streaming. Hankerson doesn’t own the masters to that debut.

Sources have said the relationship between Hankerson and the singer’s parents — he’s the brother of Aaliyah’s mother, Diane — became strained after Aaliyah’s passing as Blackground struggled to rebuild.

Although Blackground survived with a string of successful releases from Jojo, Tank, Toni Braxton and Timbaland, by 2009 the label was barely functioning after lawsuits from Braxton, Timbaland and JoJo essentially toppled it.

Talks of a further posthumous Aaliyah release resurfaced in 2012 after Reservoir Media Management announced it had acquired publishing rights to Blackground’s catalog. The news came after a posthumous Aaliyah single, “Enough Said,” was released to Soundcloud by Drake, who guested on the record and was revealed as the project’s executive producer alongside collaborator Noah “40” Shebib.

Again, the momentum was short-lived, with Shebib and Drake backing away from the project because of negative reactions from fans and the denouncement of the album from her family.

“There’s going to be a mixture of old and new on the project, but we’re really trying to make a contemporary album that will stand up to everything that’s out right now, and that will be a worthy representation of her musical legacy,” Jomo Hankerson (son of Barry and the label’s then-head) told Billboard at the time.

“The idea is to reintroduce her music to a new generation that maybe doesn’t understand the influence that they’re listening to in the music today. We just thought it was time.”

Since gaining rights to her catalog in 2012, Reservoir has done little with the music outside of licensing, including authorizing ASAP Rocky and Chris Brown to sample her material. Per its deal, it can’t act as a distributor of any of her recorded music the way a label would.

“As the music publisher of many titles performed by Aaliyah, our role is to represent her catalog’s songs, songwriters, and copyrights through careful administration and licensing, as it is our privilege to do. Our representation allows us to make this music available for licensing in films, TV, and advertisements; clear it for sampling in new recordings; celebrate its creative reinterpretations on sites like YouTube; uphold its rights in legal disputes; and support any new releases that may be made available to the public by record labels,” a statement on its site reads.

Reservoir declined to comment further.

For more music news follow me on Twitter:@GerrickKennedy

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.