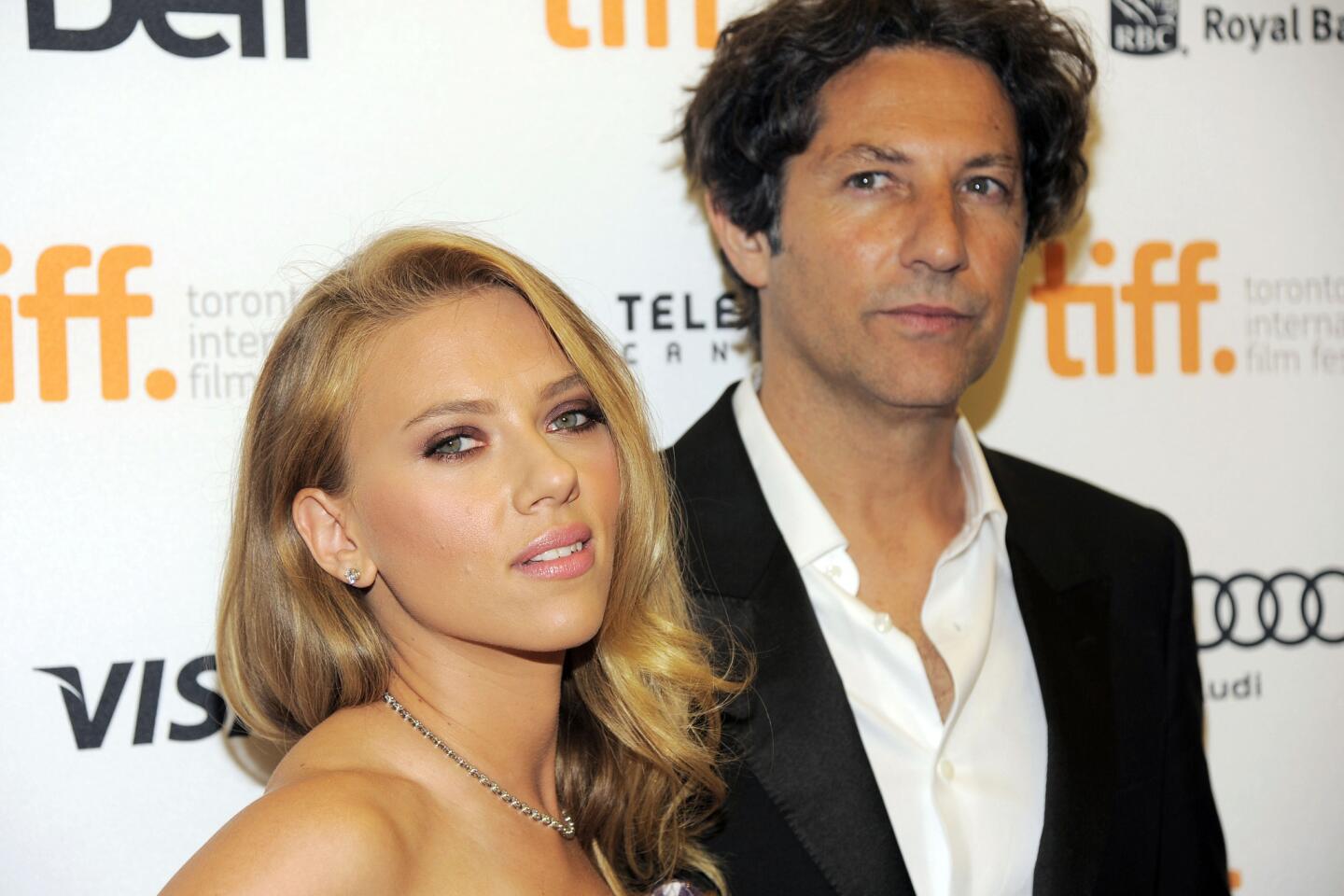

TIFF 2013: Actors James Franco, Jason Bateman, more try directing

- Share via

TORONTO — The entertainment world these days is filled with hyphenates: bubble-gum pop queens trying their hands at acting, film auteurs flocking to cable TV. At the Toronto International Film Festival this year, a different trend was on display, as a number of longtime movie actors used their connections and leverage accumulated in front of the camera to nab the big gig behind it: directing.

Every generation sees a performer or two who toggles easily between acting and directing — Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles and Clint Eastwood, to name a few. But these days, it seems to be more common for actors to take a whirl in the director’s chair. In the process, these performers are eroding a long standing culture of specialization and even reshaping how films look and feel.

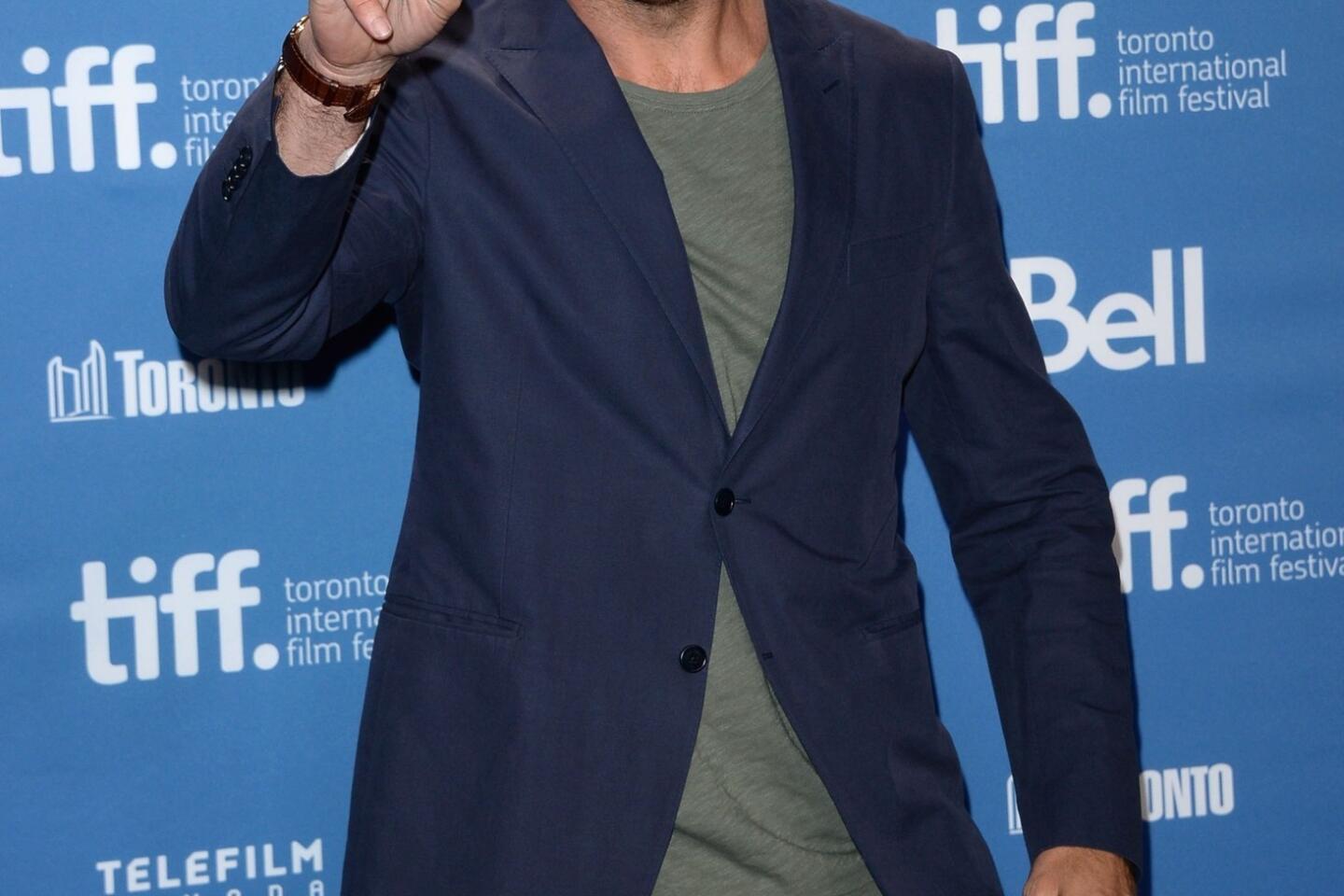

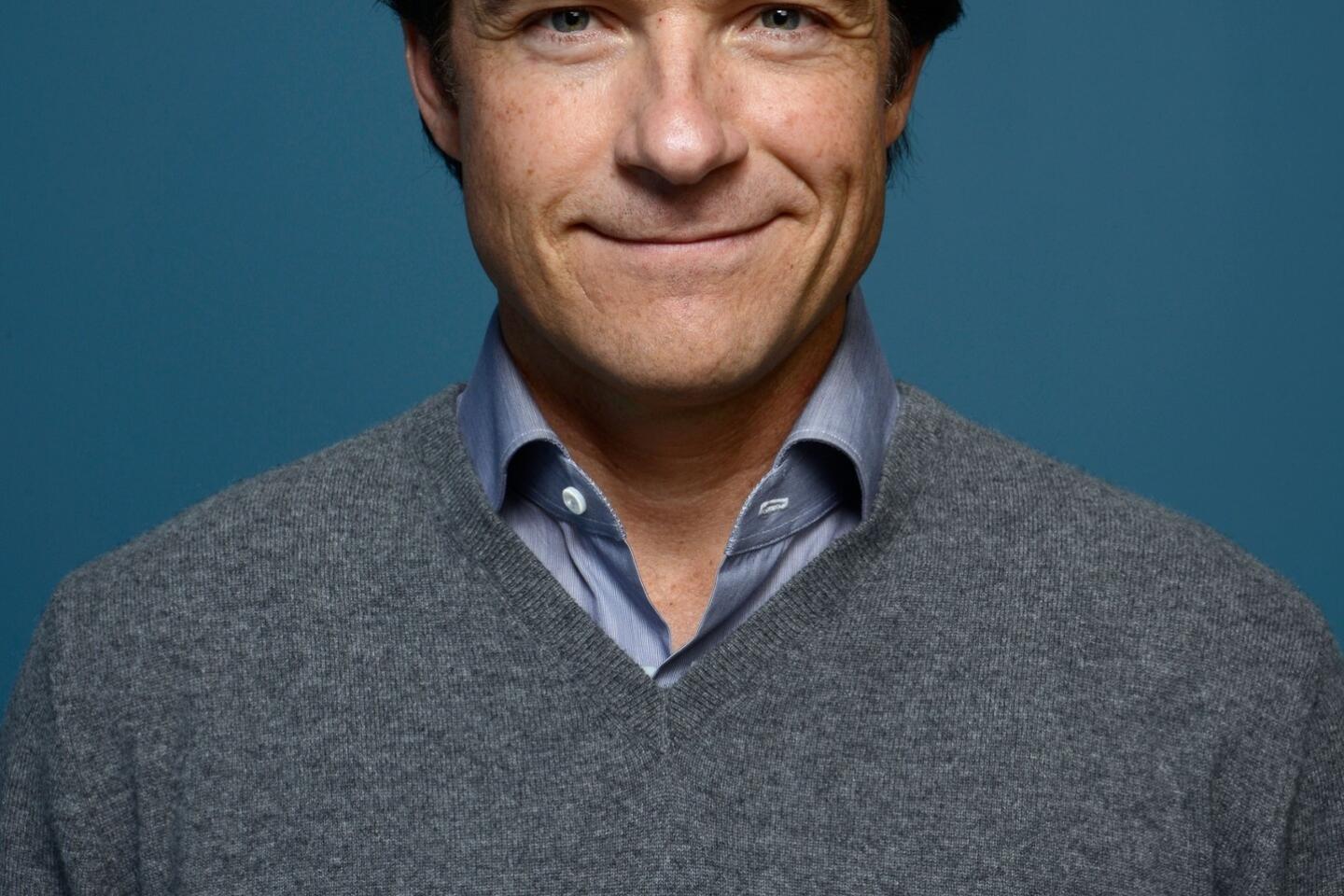

The Toronto festival, which ends Sunday, showcased at least seven diverse films made by actors, including movies by Jason Bateman (the snark comedy “Bad Words”), James Franco (the hard-boiled literary drama “Child of God”), Ralph Fiennes (the period Dickens romance “The Invisible Woman”), Keanu Reeves (the martial-arts action pic “Man of Tai Chi”), the British character actor Dexter Fletcher (the rom-com musical “Sunshine on Leith”), Mike Myers (the showbiz documentary “Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon”) and Joseph Gordon-Levitt (the sex comedy “Don Jon”).

WATCH: Toronto Film Festival trailers

It’s not just a festival thing — Seth Rogen got behind the camera for this summer’s “This Is the End,” and this fall, George Clooney, one of the most successful actor-turned-directors of the modern era, will unveil his art-heist thriller “Monuments Men.” Next year will bring movies directed by Zach Braff (a thirtysomething drama, “Wish I Was Here”), John Slattery (the gritty murder tale “God’s Pocket”) and Ryan Gosling (the dark fantasy “How to Catch a Monster”).

Ben Affleck, perhaps the most high-profile actor-director of the moment, helmed the Oscar-winning “Argo,” and in 2014 he will be directing “Live by Night,” adapted from Dennis Lehane’s crime novel (even as he’s preparing to act in “Gone Girl” and a new Batman-Superman movie).

“I don’t know if it speaks to an increased ambition on the part of the entertainment-industry workforce or more permissiveness on the part of the industry’s governing bodies,” Bateman said in an interview. “But there’s definitely a lot more of us directing now.”

At a certain level, those doing it say it’s a matter of access. The current generation of actors can hone their skills by experimenting with cameras that a previous class could only dream of.

“When Scorsese was starting to direct, you needed to have a lot of money or go to film school just to have access to the equipment,” Franco said. “Now it’s everywhere.”

PHOTOS: Toronto Film Festival 2013

Some also see the actor-turned-director trend as part of a broader shift, as more and more actors have been producing and then looking for even greater control and autonomy over their films. In midcentury Hollywood, actors were pressed into performing in one movie after another by the studios, which often owned rights to all their creative efforts. But as actors began gaining more freedom in the latter half of the century, and studios’ power waned, they began turning to producing. By the 1990s, seemingly every second actor in Hollywood had a production company.

Directing, then, represents the next step. But it may not be as simple as previous ones.

Actors who become producers usually have a partner who can do some of the heavy lifting. And in any event, being a producer doesn’t necessarily require hands-on involvement in every scene. Directing, on the other hand, is a job almost always done by one person and demands a constant on-set presence.

As actors run toward the director’s chair, they run the risk of taking on a job whose complexity they don’t fully grasp. “You hear all the time that actors who become directors know what their actors are going through, and that’s true to a large extent,” said Fletcher, who after a career of colorful roles in movies like “Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels” began directing features a few years ago.

INTERACTIVE: From Toronto to the Oscars? Well...

“But it’s also true that as an actor you can be fairly solitary and go off and construct your own character,” he said. “Then all of a sudden as a director it’s all-encompassing, and you have to manage the art department and the cinematographer and the makeup and the hair, and make that all work together. I don’t think some actors realize how hard it is to make that adjustment.”

Those doing it believe it’s worth it, despite the challenges.

For some actors, directing is a chance to examine pet subjects they never could explore otherwise. Myers had been curious about the music icon Shep Gordon since he negotiated with the manager to buy an Alice Cooper song for “Wayne’s World” two decades ago. But he probably never would have had the chance to incarnate him on screen as an actor, so he decided to direct a documentary instead. Actors have at least one advantage over their directing-only counterparts; because of their shorter work cycles, most actors have been on many more sets than pure directors have, and have come in contact with far more filmmakers. As a result, they say, they have a unique set of experiences that makes them suited to directing.

“I feel like I’ve been able to soak up a lot of wisdom from all my years working as an actor,” Bateman said. “Directors don’t have that opportunity.”

The pattern is self-reinforcing. As actors see more of their peers do it, they want in on the game too, for reasons of both control and competitiveness.

Though each personality brings his own approach, actor-directed films can have a particular feel — looser, a little more improvisational — as actors behind the camera often give performers the leeway they wish directors would always give them. (Bateman’s “Bad Words,” for instance, sold at Toronto to Focus Features, is a freewheeling, R-rated comedy.) Even someone like Eastwood, whose films are quite lean, is known for moving quickly through production in a way that’s actor-friendly.

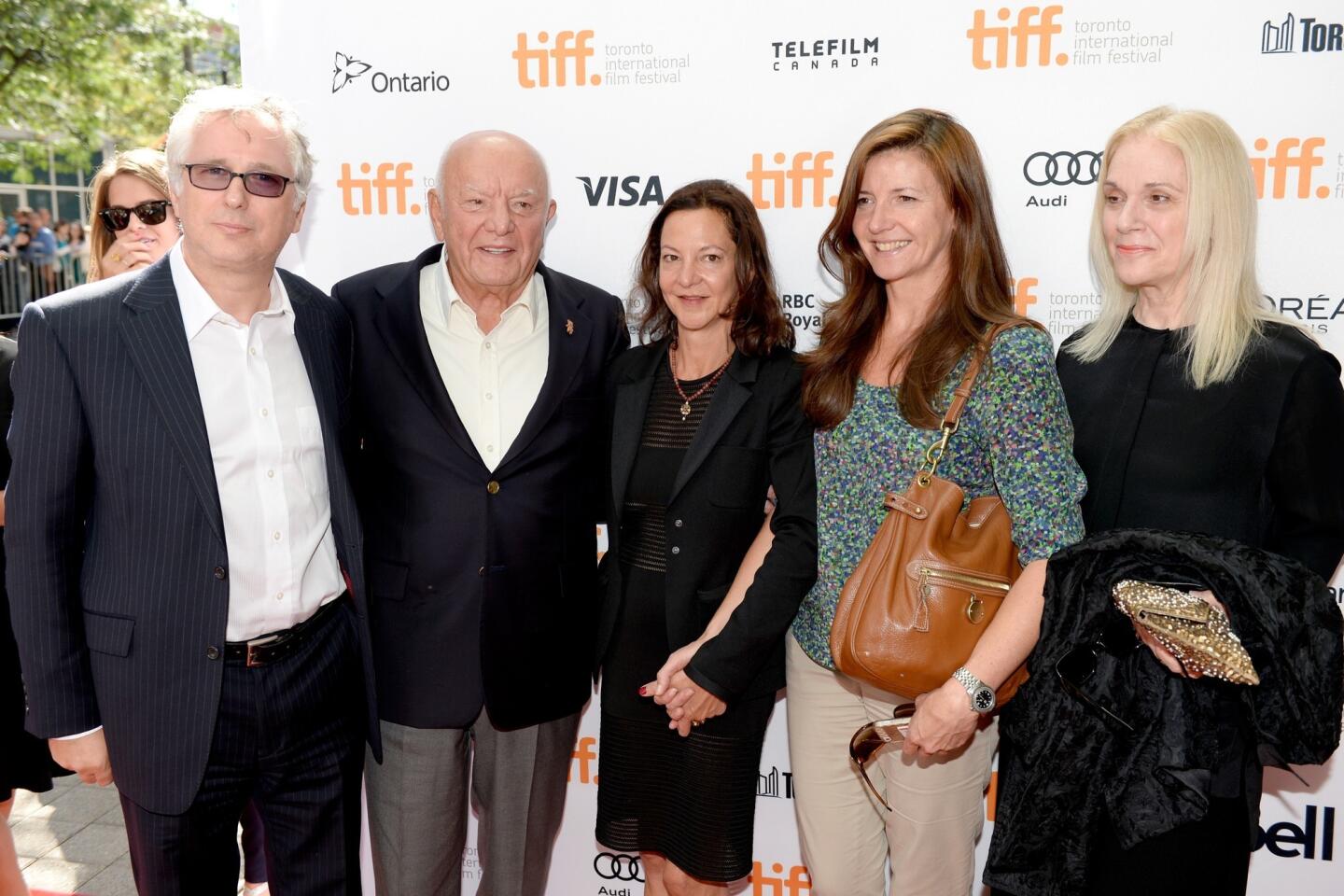

But whatever the advantages, the trend also has the potential to keep experienced directors out of the game. “I think actors should stick to their own damn jobs instead of taking jobs away from us,” joked the director Paul Haggis (“Crash,” “In the Valley of Elah”), who premiered his romantic drama “Third Person” at Toronto.

And some in the industry question whether many actors are ambidextrous enough to pull off directing. The screenwriter-screen actor (and playwright-stage thespian) Tracy Letts, who has not directed a film, says he sees creative and performance jobs as simpatico. But he questions whether they can be undertaken simultaneously, as many actor-directors do.

“Actors will always say they can do something like that, but I don’t know how they can. I find I can’t act in a play I’ve written and I don’t want to write a play if I’m going to act in it,” he said. “The idea of multi-tasking is a myth.”

Last year that seemed to be a factor for Matt Damon on the drama “Promised Land.” The actor was scheduled to direct and star in the picture, about natural gas fracking. But as the film was getting ready to shoot, he opted out of the directing job and Gus Van Sant stepped in instead.

Still, many actors say the idea of staying in their lanes is as unnatural an idea as spending most of their careers working for one studio.

“When I was just acting, it would upset me that I wasn’t able to contribute and check off all these other boxes on a film,” Franco said. “I had to start directing so I wouldn’t feel that way.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.