Toronto Diary: Festival highlights from ‘First Reformed’ to ‘Lady Bird’

Los Angeles Times critic Justin Chang on the double-Rachel feature (Rachel McAdams and Rachel Weisz) “Disobedience” and how TIFF 2017 has been a showcase of acting talent for the actress leads.

Times film critic Justin Chang is keeping a regular diary over the course of seven days at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival. He will be writing about the movies he’s seeing, the trends he’s observing and what it all means for an event that, along with the Venice and Telluride film festivals, marks the official kickoff of the fall movie season.

‘First Reformed,’ ‘Downsizing’ bring climate change to the fore

“Will God forgive us for destroying his creation?” The man asking the question is the Rev. Toller (Ethan Hawke), an ex-military chaplain-turned-rural minister who finds himself undergoing a profound crisis of faith. He has already lost a son and a wife, and his insides are rotting from cancer, all of which might well drive even a devout believer to feel that God has abandoned him. But what genuinely haunts Toller, and inspires him to consider an act of extreme, violent desperation, is his eye-opening encounter with Michael (Philip Ettinger), a militant eco-activist who is terrified by the prospect of humanity’s mass extinction.

“First Reformed,” Paul Schrader’s somber, beautifully composed and entirely mesmerizing new drama, is not a work of particular subtlety. Its moral argument is as clear and crystalline as its images, shot by cinematographer Alexander Dynan in the nearly square academy-aspect ratio. The severity of Toller’s convictions, as well as his disgust at the knowledge that his church has taken money from one of the town’s biggest polluters, gives rise to an angry, confrontational question: Why have so many Christians rejected the science of climate change, effectively abdicated their God-given responsibility to look after the Earth?

Speaking as a believer who has often pondered that and other dispiriting questions about why evangelical Christianity has been so readily co-opted by conservative politics, I’ll confess that the heaviness of Schrader’s moral inquiry and the earnestness of his provocations were right up my alley. And it’s nothing short of fascinating to watch the director reconcile the queasy momentum of a thriller with the hushed, transcendental austerity of the masters he’s emulating: Even if Schrader hadn’t acknowledged his debt to “Diary of a Country Priest,” the visual and dramatic parallels between his film and that 1951 Robert Bresson masterpiece would be more than apparent. (Ingmar Bergman’s “Winter Light” looms heavily over the proceedings too.)

“First Reformed,” which played at the Venice and Telluride film festivals before arriving in Toronto, is an exceptional return to form for Schrader after several much-maligned disappointments (“The Canyons,” “Dying of the Light”). It continues the director’s career-long grappling with his Calvinist beliefs, even as it becomes the latest iteration of a story he has told before, in movies like “American Gigolo” and “Hardcore” and his screenplay for “Taxi Driver.” (Amanda Seyfried is piercingly good as the environmentalist’s pregnant wife, whose relationship with Toller sets the drama fatefully in motion.)

Above all, perhaps, it is a timely reminder that Ethan Hawke is one of the most reliable and severely underrated actors working today; he holds nearly every frame of this picture with the initially calm, easygoing demeanor of a friendly neighborhood pastor, only to give way to greater and greater fits of rage and torment. At the film’s Venice press conference, Hawke noted that he had been “surrounded by religion” his entire life, and that his great-grandmother once wanted him to enter the priesthood. He may not have been destined to be a man of the cloth, but “First Reformed” leaves no doubt he was born to play one.

The issue of climate change also figures prominently in Alexander Payne’s wry science-fiction comedy “Downsizing,” though only at the end of a long and convoluted story that seems to be making itself up as it goes along. For a while, that’s not such a bad thing. The movie has an enjoyable opening hour in which it lays out the basics of its rigorous, ludicrous premise: In a not-so-distant future, an unprepossessing nice guy named Paul Safranek (Matt Damon) opts to shrink himself to just a few inches tall, availing himself of a dynamic new procedure devised by Norwegian scientists that promises stability and even prosperity in an unforgiving economy.

If Paul is shrinking himself, it’s nice for a while to see Payne stretching himself. He’s still working in the barbed humanist vein of films like “Sideways,” “The Descendants” and “Nebraska,” but this time with an out-there twist that raises far broader implications beyond Paul’s quality of life. “Downsizing” begins as a high-concept farce, morphs into a satire of class, consumerism and globalization, and ends with a sincere lament for Third World suffering and the sustainability of the planet.

But the reach of the movie’s topical ambitions far exceeds its tonal grasp. More often than not, Payne’s preferred method of trying to squeeze laughs and tears from the same moment — or rather, following a lump-in-the-throat moment with a carefully timed comic jab — simply cancels itself out. There’s an emotional flatness to this movie, which doesn’t feel like it’s bursting with ideas so much as meandering noncommittally from one to the next.

Damon comes off as a total shlump, but that’s what his Everyman role more or less calls for. Elsewhere, there’s fine supporting work from Kristen Wiig as Paul’s wife and from the eccentric duo of Christoph Waltz and Udo Kier as a couple of pint-sized opportunists who give the proceedings a regular jolt of comic energy. Enlisted for a similar purpose, but also an ostensibly grander one, is Hong Chau, who turns up in the role of Ngoc, a disabled Vietnamese refugee who was forced to undergo the shrinking procedure against her will. Despite her sufferings, which (ahem) dwarf Paul’s significantly, she retains an energetic can-do spirit and an unflagging empathy for the most marginalized people in this diminutive society.

“What an inspiration,” you’re meant to think. “What a crock,” I concluded. There’s an art to depicting a character who speaks in broken pidgin English without lapsing into caricature, but Payne, whose writing is rarely more condescending than when it’s straining for sensitivity, may not be the artist to pull it off. Chau is an excellent actress (as borne out even by her minor role in “Big Little Lies,” which I had the pleasure of bingeing right before Toronto), but Ngoc is an appalling creation. Ridiculed and sanctified in equal measure, she’s the kind of sop to on-screen diversity that makes you wish the filmmakers had left white enough alone.

The dead-dad dramas of ‘Disobedience’ and ‘Dark River’

Covering the Toronto International Film Festival can sometimes make you feel like one of those fabled blind men touching the elephant.

Trying to find a unifying festival theme, a favorite sport of journalists but a dubious endeavor under most circumstances, becomes outright impossible at a festival as immense as this one. (The 2017 edition, although slimmed down from last year’s program by a reported 20%, boasts no fewer than 255 features.) Every attendee is on his or her own unique track, and while we can certainly identify dramatic and thematic parallels within those tracks, ascribing some sort of grand narrative to the festival as a whole is generally a fool’s errand.

So, I won’t make too much of the fact that a few of the movies I’ve seen in the last several days seem to be carrying on a conversation about the plight of young people chafing against the social and cultural restrictions imposed by their families. Going deeper still, the movies I’m thinking of all address the specific plight of women and their difficult relationships with their fathers, whose sins run the gamut from being unreasonably demanding to inflicting acts of physical and psychological abuse.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Aaron Sorkin’s biographical drama “Molly’s Game,” which I wrote about in my previous entry, is the notion that Molly Bloom (Jessica Chastain), a Colorado-born cocktail waitress who found herself running a high-stakes New York gambling operation, has conceived her entire scheme as an act of revenge against her intensely tough and critical father (Kevin Costner). It’s likely to be the most criticized element of the story, insofar as it uses deep-seated daddy issues to lightly chip away at our heroine’s psychological armor, but it’s also a possibility that the movie playfully considers, and critiques, in ways both humorous and cathartic.

By contrast, we never see father and daughter together in Sebastián Lelio’s somber and passionate new drama, “Disobedience,” which begins with the death of a celebrated Orthodox rabbi in North London — a loss that brings his only child, Ronit (Rachel Weisz), back home from New York to settle her father’s estate. Received with frosty politeness by the community she fled years ago for a life of secular freedom, Ronit gradually rekindles her friendship with Esti (Rachel McAdams), whom she is surprised to learn is now the wife of Dovid (Alessandro Nivola), a spiritual disciple of Ronit’s father.

As will soon come to light, in a series of erotic encounters that are at once tasteful and unusually candid for a prestige drama, Ronit and Esti carry a torch for one another that years apart has failed to extinguish. That more or less explains why Ronit left, but the film, adapted from Naomi Alderman’s 2006 novel, is equally curious about why Esti stayed. Both Rachels are superb here, and if Weisz is ultimately the story’s anchor, the grieving outsider whose perspective we share at every moment, then McAdams is its secret weapon: She’s piercing to watch as she reveals the cracks in her character’s quietly contented facade, in a story that takes the full measure of her tragedy as well.

The intensity of repressed feeling coursing beneath so much grave religiosity has already led some to liken the film to an Orthodox Jewish retelling of “Carol.” It’s not at all an unflattering comparison; I’d add only that “Disobedience,” with its gray, muted palette, also reminded me at times of “Beyond the Hills,” the grim 2012 Romanian drama about inconvenient lesbian desires threatening the sanctity and order of an Orthodox convent.

But Lelio, a gifted Chilean writer-director (“Gloria”) making his first English-language feature, remains exquisitely attentive, even generous, to the people and circumstances surrounding Ronit and Esti. He understands that desire and identity don’t take shape in a vacuum, and that while religion can be an instrument of oppression, it can also be a source of deep, abiding mystery.

I headed straight from “Disobedience” on Sunday night to the premiere of Clio Barnard’s superbly atmospheric “Dark River,” another movie that begins with a daughter’s homecoming after her father’s death. This one, however, is set not in London but rather in the farther-flung sheep pastures of Yorkshire, where a woman named Alice (Ruth Wilson) has spent 15 years drifting and working as a shearer. Once she learns of her dad’s passing, she immediately returns home to claim tenancy of her family’s small farm, to which she believes she is entitled, although her rough, ill-tempered brother, Joe (Mark Stanley), obviously has different ideas in mind.

Adapted and significantly changed from Rose Tremain’s France-set novel “Trespass,” “Dark River” is both a ferocious drama of sibling animus — beautifully enacted by Wilson and Stanley — and a harrowing chronicle of abuse. We glimpse Alice’s physical violation at her father’s hands in brief, splintered flashbacks, which Barnard weaves into her narrative with shivery skill. Audiences who have seen the director’s brilliant experimental documentary “The Arbor” (2011) and her heartrending drama “The Selfish Giant” (2013), know her skill at conjuring a bleakly enveloping sense of place, and this movie, with its wild, rugged moors pelted by sudden rains, is no exception.

“Dark River” is screening in Toronto’s Platform competition, as is “What Will People Say,” a strong second feature directed by Iram Haq, whose 2013 debut, “I Am Yours,” was informed by her own experiences growing up in Norway as the daughter of Pakistani immigrants. Her follow-up, by the director’s own admission, is even more hair-raisingly personal. It tells the story of 16-year-old Nisha (Maria Mozhdah), who, after being caught with a boy in her bedroom by her father (Adil Hussain), is effectively kidnapped by her own family and sent to live with relatives in Pakistan, a world that could scarcely be more different from the snowy Norwegian town she once called home.

My thoughts kept returning to “What Will People Say” while I was watching “Disobedience,” insofar as both films are about insular communities that can become religious and cultural prisons, especially for young daughters who fail to live up to their parents’ exacting (double) standards of sexual purity. In Haq’s film, we repeatedly hear Nisha’s parents complaining about how her actions have exposed them to deep social shame, though it’s a measure of where this film’s sympathies ultimately lie that we hear more about that shame than we actually see it.

‘The Shape of Water’ triumphs in Venice, while ‘Molly’s Game’ comes up aces in Toronto

The announcement Saturday that Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” had won the Golden Lion, the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, came as both heartening news and a reminder that, while one major film gathering is crazy enough, two unfolding simultaneously can be a recipe for pure madness.

I was at TIFF in 2009 when word reached us that Samuel Maoz’s “Lebanon,” a drama notable for unfolding entirely within the tight confines of an Israeli tank, had just won the Golden Lion in Venice. Within minutes, a small, high-concept war movie from a little-known filmmaker became Toronto’s hottest ticket, causing a near-stampede among journalists racing to get to the next screening.

Maoz came close to repeating that victory Saturday: His long-overdue follow-up feature, “Foxtrot,” won Venice’s second-place grand jury prize. Whether or not that honor raises the film’s profile here in Toronto, it deserves to. A wrenchingly acted, ingeniously structured drama about Israeli parents (Lior Ashkenazi and Sarah Adler) grieving the loss of their soldier son, “Foxtrot” is both a logical companion piece to “Lebanon” and a marked improvement on it. This time, the formal conceits enhance and deepen the tragedy rather than stifling it.

But the big winner of the day, and the first American film to take the Golden Lion since Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere” in 2010, was “The Shape of Water,” a densely imagined period fantasy that marks an exquisite return to form for Del Toro. Already warmly embraced by festival audiences in Telluride, Colo., and set to premiere in Toronto on Monday evening, the movie tells of a most remarkable discovery — an amphibious humanoid creature, found somewhere off South America — that is being kept locked in a tank at a U.S. government facility amid the mounting Cold War anxieties of 1962.

If that seems plenty outlandish already, rest assured that Del Toro is just getting started. Always a spirited devotee of old-school Hollywood genres, the director achieves an inspired melding of creature feature, spy thriller and wondrously perverse love story, the latter sustained by Sally Hawkins’ achingly delicate performance as Eliza, a mute cleaning lady who immediately bonds with the imprisoned merman (played, naturally, by Del Toro’s prosthetic-happy muse, Doug Jones).

But then, there’s great acting everywhere you look in “The Shape of Water,” from Octavia Spencer and Richard Jenkins as Eliza’s loyal friends, Michael Stuhlbarg as a doctor who becomes an unexpected ally, and Michael Shannon, almost too ideally cast as a scarily menacing federal agent.

Like Del Toro’s 2006 triumph, “Pan’s Labyrinth,” “The Shape of Water” is a once-upon-a-time fairy tale rooted in a specific historical moment. It’s rich and transporting, if also a bit calculated in its lyricism; you can sometimes see Del Toro’s mental gears spinning as he writes his characters into one corner after another. But there’s no denying they spin with passion.

Elsewhere, I hope Toronto festival-goers (to say nothing of the broader art-house audience) will have the chance to see some of the other Venice prizewinners playing here. I was glad I made time for “Custody,” a razor-sharp, genuinely harrowing story of a very bad dad (the terrifying Denis Ménochet) terrorizing his young son and his soon-to-be-former wife. It’s an impressive feature debut for French filmmaker Xavier Legrand (an Oscar nominee in the short film category), who duly won the Venice jury’s Silver Lion for best director, and who stands a shot at winning another prize in Toronto’s Platform competition.

Also screening in that program is Warwick Thornton’s “Sweet Country,” a deliberately paced, morally bruising tale of frontier violence set in 1929 Alice Springs, in Australia’s Northern Territory. Like his 2009 debut, “Samson & Delilah,” the new film, which won a special jury prize in Venice, finds Thornton expressing a palpable anger at the brutal mistreatment of his country’s Aboriginal people, in a style that melds classical western filmmaking with studied art-film longueurs.

Few people are having a busier festival season than Annette Bening, who not only served as president of this year’s Venice jury but also has a new movie, “Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool,” which is screening here in Toronto following its Telluride premiere. Directed by Paul McGuigan (in a decisive change of pace after “Victor Frankenstein”), the film offers a “My Week With Marilyn”-style gloss on the life of the great, oft-neglected stage and screen actress Gloria Grahame (Bening), who won an Academy Award for “The Bad and the Beautiful” and who is perhaps best remembered now for her heartbreaking performance opposite Humphrey Bogart in Nicholas Ray’s 1950 noir masterpiece, “In a Lonely Place.”

“Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool” regards Grahame through the eyes of a young Brit named Peter Turner (Jamie Bell), who was an up-and-coming actor in his 20s when he began a love affair with Grahame, a woman almost 30 years his senior. At the time, Grahame was trying to re-energize her acting career on the London stage, and the movie glides between sunny California and not-so-sunny England, between Grahame’s tempestuous romance with Turner and her later years wasting away from cancer in Liverpool, under the care of Turner and his family. The movie is wanly conventional but affecting, and Bell holds his own very nicely opposite Bening, who marbles her gift for emotional nuance with a palpable respect for her character’s often shabbily treated Hollywood legacy.

Whether the feat of playing an Oscar winner will finally net that elusive lead actress statuette for Bening herself is one of the questions looming over this year’s awards-season landscape — one that might have been settled, perhaps, if the actress had received the honors she deserved for last year’s “20th Century Women.” As it is, the latest Toronto chatter suggests she may face another stiff round of competition this time from a field that includes Hawkins in “The Shape of Water”; Margot Robbie in the Tonya Harding biopic “I, Tonya”; Frances McDormand, so commanding in Martin McDonagh’s small-town noir “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri”; and Jennifer Lawrence, the beating heart of Darren Aronofsky’s thrilling and divisive “mother!”

I’ll have more to say about “mother!” in my review for The Times when the film opens in theaters. But I’ll reserve a few words here in praise of Jessica Chastain, who is rightly drawing raves for her forceful, breathtakingly controlled work in “Molly’s Game.” Aaron Sorkin’s directorial debut tells the fiendishly complicated story of how a very smart 26-year-old named Molly Bloom (Chastain) came to operate a high-stakes gambling ring that pulled in Hollywood celebrities, Wall Street billionaires and Russian mobsters — a recipe not only for a very expensive disaster but also for a sensationally entertaining movie that maintains a tight grip on the audience over nearly 2½ hours.

Not least among its accomplishments, “Molly’s Game” drives a nail into the coffin of the idea that voice-over is an anti-cinematic device. Sorkin remains a master of breathless, hyper-articulate verbiage; you could cut yourself with some of the dialogue volleys that Molly and her attorney (an excellent Idris Elba) fling back and forth. But in contrast with his fact-based scripts for “The Social Network” and “Steve Jobs,” he relies heavily this time on his protagonist to tell her own story, and she does so, with nearly wall-to-wall narration that doesn’t waste a single word.

It’s a pointed decision from a writer who has often been taken to task for his representations of women, and who has clearly decided to greet that charge head-on. The gamble paid off. By the end of “Molly’s Game,” Chastain isn’t the only one looking like a winner.

The brilliance of Saoirse Ronan and the thrilling challenge of 'Zama'

What comes to mind when you hear the name Greta Gerwig? Maybe it’s the cancer-stricken punk-feminist photographer she brought to such vivid life in last year’s “20th Century Woman,” or the delightfully loopy screwball princesses she played in “Mistress America” and “Damsels in Distress.” For me, it’s the blissful image of Gerwig running in “Frances Ha,” her arms flailing and her hair whipping behind her as she sprints and leaps down a New York Chinatown street — an ebullient vision of carefree innocence set to the crackling beat of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

FULL COVERAGE: Toronto International Film Festival 2017 »

I thought about that image a few times during “Lady Bird,” a delightfully spry and smart high school comedy that marks Gerwig’s solo directing debut. (She co-directed the 2008 indie “Nights and Weekends” with Joe Swanberg.) Set during the early 2000s, a time of clunky desktop computers and news of the Iraq war blaring from every TV screen, the movie follows a fiercely independent Sacramento teenager named Christine (Saoirse Ronan) — or Lady Bird, as she has defiantly rechristened herself — as she tries to deal with an overly critical mother (Laurie Metcalf), changing friendships, all manner of boy trouble and the usual anxieties about college and the future.

In other words, “Lady Bird” isn’t out to reinvent the coming-of-age genre, though what it lacks in originality it makes up for in sheer velocity. The movie runs 94 minutes and moves like the wind. Gerwig paces every comic episode so briskly, and with such a joyous sense of forward propulsion, that we feel effortlessly caught up in what we’re watching: not a series of carefully plotted mishaps and epiphanies, but rather the swiftly pulsing beats of time — and life itself — passing our heroine by.

Not every actor-turned-director with a distinctive on-screen presence necessarily brings that presence to bear on their filmmaking; I’d go so far as to say most of them don’t. This year’s Toronto program offers a number of opportunities to test that theory, including Angelina Jolie’s “First They Killed My Father,” a well-received drama set during the 1970s Cambodian genocide, and George Clooney’s “Suburbicon,” a misfired attempt to reinvigorate the dark-underbelly-of-the-American-dream subgenre through a racially segregated 1950s prism.

Gerwig has noted the semi-autobiographical nature of her story, but a basis in real life alone wouldn’t be enough to make it ring true. The casting is impeccable down to the smallest role; there are terrific performances by Beanie Feldstein as Lady Bird’s loyal best friend, Lucas Hedges as her theater-geek crush, Tracy Letts as her easygoing dad and, best of all, Metcalf as a mother who shows how resentment can be an act of love (and also how it can’t).

And then there is Ronan, who, whether or not she resembles the 2002-era Greta Gerwig, owns her role with a flinty intelligence and piercing vulnerability that makes you want to follow her anywhere she goes — by which I don’t mean just Christine/Lady Bird, but also Ronan herself. This remarkable actress has gone from strength to strength in recent years, peaking with her astonishingly fine-grained work in “Brooklyn,” in which she played a very different young woman tentatively finding her way in the world.

Ronan is so good that she can emerge smelling like a rose even from a well-mounted if ultimately unsatisfying effort like “On Chesil Beach,” her other picture playing in Toronto this year. Seeing that movie back-to-back with “Lady Bird,” if anything, only underscored the actress’ versatility: Whereas Gerwig’s film casts her as a 21st century American teenager eager to fall in love and shed her virginity, “On Chesil Beach” locks her into the role of Florence, a British woman who embodies the buttoned-down timidity of the stifling, pre-sexual-revolution 1960s.

Adapted by Ian McEwan from his own novel, the movie centers on Florence and her genial, slightly awkward new husband, Edward (Billy Howle, likable but not quite up to the level of his more established co-star), as they make an ill-fated attempt to consummate their marriage. A painfully awkward beachside retreat is interspersed with telling flashbacks to their respective histories, resulting in a lumpy, lurching back-and-forth structure that suggests a movie forever clearing its throat to articulate something meaningful.

Individual scenes play deftly enough; the director, Dominic Cooke, is a theater veteran making his feature debut, and he coaxes as much emotional truth out of this clenched, overdetermined scenario as possible (as well as a certain degree of cringe-inducing comedy). And Ronan, who came to prominence in a considerably better McEwan adaptation called “Atonement,” gives eloquent voice and conviction to Florence’s repression. Her tempestuous emotions complicate a story that often feels too tidy by half.

“Too tidy by half” are not words that any critic will level against the South American period epic “Zama,” which surely ranks among the most challenging, intricately structured and formally innovative pictures playing in Toronto. Like the previous features directed by the brilliant Argentinean filmmaker Lucrecia Martel (“La Ciénaga,” “The Holy Girl,” “The Headless Woman”), this isn’t just a movie but a full-on miasma — a humid, atmospheric vision of a complex world conjured from the inside.

Every new scene presents itself as a kind of puzzle in which viewers must continually reorient themselves. Do not look to any of the characters to walk you through who they are, what happened before or what will happen next. “Zama” doesn’t filter history through an easily clarifying prism. Through her sly editorial disjunctions, her tactile, off-center compositions and her wild, teeming sonic landscape, Martel conjures the haunted interiority of the past. She brings history into an uncomfortably intimate present tense.

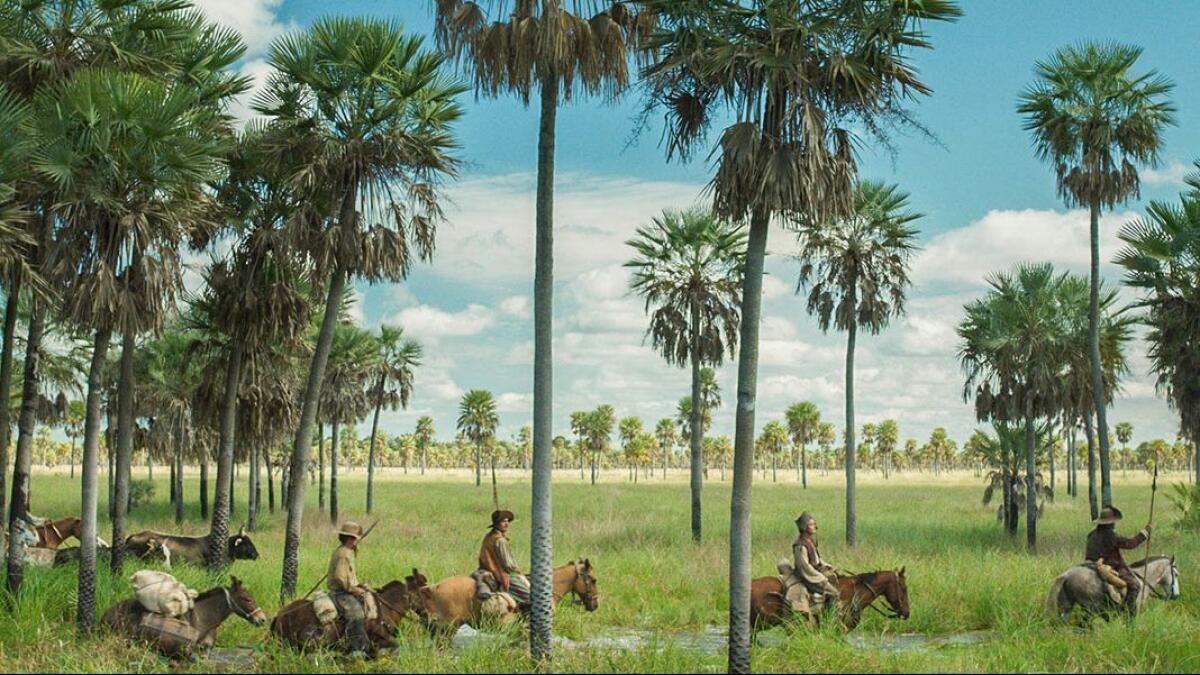

The film is an adaptation of Antonio di Benedetto’s 1956 novel about Diego de Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho, never cracking a smile), an official of the Spanish crown who has been stationed for years at a remote outpost in what is now Paraguay, where he is impatiently awaiting a transfer. But it’s immediately clear from the outset that Zama’s wait will be in vain, and that as he wearily seeks a series of favors — from a local minister or a teasing noblewoman (Lola Dueñas, a regular of Pedro Almodóvar, one of the film’s co-producers) — we will observe the stagnation and rot of the colonialist experiment firsthand.

In “The Headless Woman,” her 2008 puzzler about a woman who may or may not have run over a child with her car, Martel gave us a dark comedy of bourgeois indictment, evoking the woman’s concussed, amnesiac state without assuaging, let alone absolving, her guilt. Emerging nearly 10 years later and set more than two centuries earlier, “Zama” nonetheless suggests a curious extension of that film’s waking nightmare, in which the scars of oppression are no less evident. Watch how carefully Martel etches the brutal reality of slavery in her images, the way she uses crowded frames and half-naked bodies to suggest humanity matter-of-factly choking the life out of its own. Even before the movie erupts in a fatal, inevitable crescendo of violence, you can feel dread emanating from every pore.

“Zama” isn’t easy. I saw it for the first time last week at the Venice Film Festival, where I was in attendance as a guest of the Biennale College program, and I don’t mind admitting that my intense jet lag, confronted with Martel’s attention-demanding style, kept me from getting more than a foothold. A wide-awake second viewing in Toronto with a packed press audience — most of whom, despite a few walkouts, clung to every perplexing, thrilling moment — felt revelatory, even restorative. This is a long-overdue return from a master filmmaker whose next cinematic enigma is hopefully not another decade off. “Zama” may be a challenge, but at this point in the festival, it also feels like a gift.

Wiseman’s ‘Ex Libris’ enthralls, while ‘Borg/McEnroe’ serves its purpose

For better and for worse, the Toronto International Film Festival is an event that invites bold predictions, most of them involving the months-long industry and media grind that we call awards season. Four years ago, Steve McQueen’s “12 Years a Slave” so galvanized audiences here that a number of journalists declared the race for the best picture Oscar effectively over. (They were right.) It’s still too early in this year’s 42nd annual festival for anyone to have made a similar declaration yet, although a few tantalizing narratives have already begun to surface.

One of these is the widespread adoration of “Call Me by Your Name,” Luca Guadagnino’s intoxicating coming-of-age love story, which has enraptured festival audiences (myself included) since its first screenings at Sundance. Its spell showed no signs of abating in Toronto, where it screened for a public audience on Thursday night, with Guadagnino in attendance with his stars Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer.

And speaking of actors, in the next few days festival-goers will spend minutes in line parsing the Oscar prospects of overdue stars like Gary Oldman and Annette Bening, whose respective films, “Darkest Hour” and “Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool,” are set to screen here after making their festival debuts in Telluride, Colo., last week.

Oscar buzz has become a necessary evil at Toronto. On one hand it ensures the packed houses, bustling red carpets and gobs of press coverage that keep this festival running year after year. But it also inevitably overshadows the many, many worthy films that arrive here with no media profile or awards prospects of which to speak, and which have little hope of finding a commercial audience anywhere near as sizable or enthusiastic as the up-for-anything crowds packing Toronto screening venues this week.

To partially redress that sad state of affairs, allow me to make my own prediction — an impish and utterly unprovable one, measurable only by the whimsies of personal taste, but one that I believe has a decent chance of holding true when the festival is over. Namely, there will be no better new movie at TIFF this year than “Ex Libris — The New York Public Library,” Frederick Wiseman’s almost indecently rich and stimulating new documentary, which represents a landmark achievement even in the context of this master filmmaker’s career.

First presented last week in competition at the Venice Film Festival, “Ex Libris” screened Thursday for press and industry audiences in Toronto, or at least the handful who were willing to set aside three hours and 17 minutes for an impassioned deep-dive portrait of an invaluable institution. Limiting himself to 11 of the New York Public Library’s 92 branches, and returning continually to its fabled flagship building on Fifth Avenue opposite East 41st Street, Wiseman sifts through lectures, classes, Q&As, policy meetings, tutoring sessions and stage performances to build a mighty case for the library as the city’s social and intellectual lifeblood.

From an onstage conversation with Elvis Costello to a community discussion of the misrepresentation of slavery in McGraw-Hill textbooks to a Gabriel Garciá Márquez book group so smart and impassioned that I wanted to sign up for it immediately, “Ex Libris” demonstrates Wiseman’s usual genius at constructing a mosaic of the quotidian. As always, we are never with any one story for very long, although there are a few threads to which the film keeps returning, none more significant than a staff meeting to determine how best to digitize the library’s materials and boost online use in a city where many New Yorkers still don’t have access to the Internet.

“Libraries are not about books,” one observer notes. “Libraries are about people.” And because Wiseman’s cinema has always concerned itself with people — people at work, people in conversation, people helping others, people trying to better themselves — it would be hard to imagine a more fitting alchemy of filmmaker and subject. His films have always been, to some degree, about the pursuit of knowledge, a fact that gives “Ex Libris” the feel of an epic career summation.

It would also be hard to imagine a subtler or more devastating rebuke of the anti-intellectualism embodied by the Trump administration, which has spent much of the past year threatening the funding of arts and cultural institutions nationwide, libraries included. “Ex Libris,” which opens in theaters later this month through Zipporah Films, offers a troubling reminder of what we stand to lose if greedy, short-sighted policies are allowed to prevail. But the movie is the opposite of pessimistic: It suggests that the desire for knowledge, creativity and community is its own sustaining, revitalizing impulse.

The festivities got off to a slick, serviceable start on Thursday night with the official opening-night selection, “Borg/McEnroe,” a slick, lightweight dramatization of the nail-biting 1980 Wimbledon showdown between those powerhouse players, Björn Borg and John McEnroe. Directed by the Danish-born Janus Metz, it’s one of a few films this year that suggest TIFF might as well temporarily change its name to the Tennis International Film Festival; the others include “Battle of the Sexes,” starring Emma Stone and Steve Carell as Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs, respectively, and “Love Means Zero,” Jason Kohn’s documentary about the legacy of star tennis coach Nick Bollettieri.

At times suggesting a less adrenalized version of Ron Howard’s Formula One rivalry saga, “Rush” (2013), “Borg/McEnroe” is an involving if low-impact study in emotional contrasts. Cross-cutting between his protagonists in precise, well-targeted editorial volleys, with occasional flashbacks to their respective troubled childhoods, Metz shows how the cool, calculating Swedish stud and the foul-mouthed American hothead may have had more inner demons in common than you might expect.

That tidy psychological construct is reinforced by fine performances from the Swedish-born Icelandic actor Sverrir Gudnason, whose brooding affect captures the machine-like precision and emotional containment that defined Borg’s behavior on (and mostly off) the court, and from Stellan Skarsgard as Borg’s long-suffering coach, Lennart Bergelin. And Shia LaBeouf, always an erratic talent, acquits himself nicely, or not so nicely, as McEnroe; there’s something fitting about enlisting one notoriously filter-free bad boy to play another.

There have been far better and far worse TIFF opening-night movies than “Borg/McEnroe,” which is fast-paced, inoffensive and about as emotionally resonant as your next poutine. But few have been more emblematic of the reality that film festivals have become their own competitive sport — a kind of cinephile Grand Slam.

The year begins with Sundance and Berlin, both held shortly after the Australian Open in January, then builds to the Gallic prestige of Cannes in May, right before the French Open. There may be no Wimbledon equivalent on the festival calendar, but the U.S. Open works overtime to make up the difference, falling at roughly the same time as Venice, Telluride and Toronto.

And of course, that fall trifecta constitutes a competition unto itself, one that threatened to turn nasty three years ago when Toronto, irked by Telluride’s early access to some of the season’s most coveted films, sought to impose a penalty of sorts by restricting all Telluride-screened titles from screening the first weekend of TIFF.

Since then those rules have relaxed and the tensions have largely blown over. Venice, Telluride and Toronto have mostly learned to share and play nice, as they have done for the four-plus decades that all three have been in existence.

The system, as it is, still sends an enormous glut of films scrambling for a limited number of slots, hopefully bolstering their Oscar hopes and burnishing the festivals’ reputations in the process. And as the films roll out (or worse, even before they roll out), we find ourselves treating their fortunes as sport, pitting them against each other, judging their long-term prospects with critics and academy voters, and effectively dividing them into winners or losers.

Cannes or Venice? Telluride or Toronto? “Moonlight” or “La La Land”? In a system so driven by narratives of competition, it can be awfully hard to appreciate the actual art that ostensibly motivates all this premature handicapping. It’s a problem from which I certainly don’t exempt myself; on the contrary, I’m as invested as anyone in seeing my own personal favorites duly and tangibly rewarded.

Which brings me to a concluding thought and my own shameless awards-season plug: Frederick Wiseman received an honorary award earlier this year from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, an organization that has never seen fit to nominate one of his films for an Oscar for documentary feature. Wouldn’t the release of “Ex Libris” suggest the perfect opportunity to rectify that particular injustice?

UPDATES:

10:30 a.m., Sept. 9: This article was updated with Day 2 highlights.

This article was originally published at 11:35 a.m., Sept. 8.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.