From the Archives: Q&A with Gregory Peck: How the Finch Stole Christmas

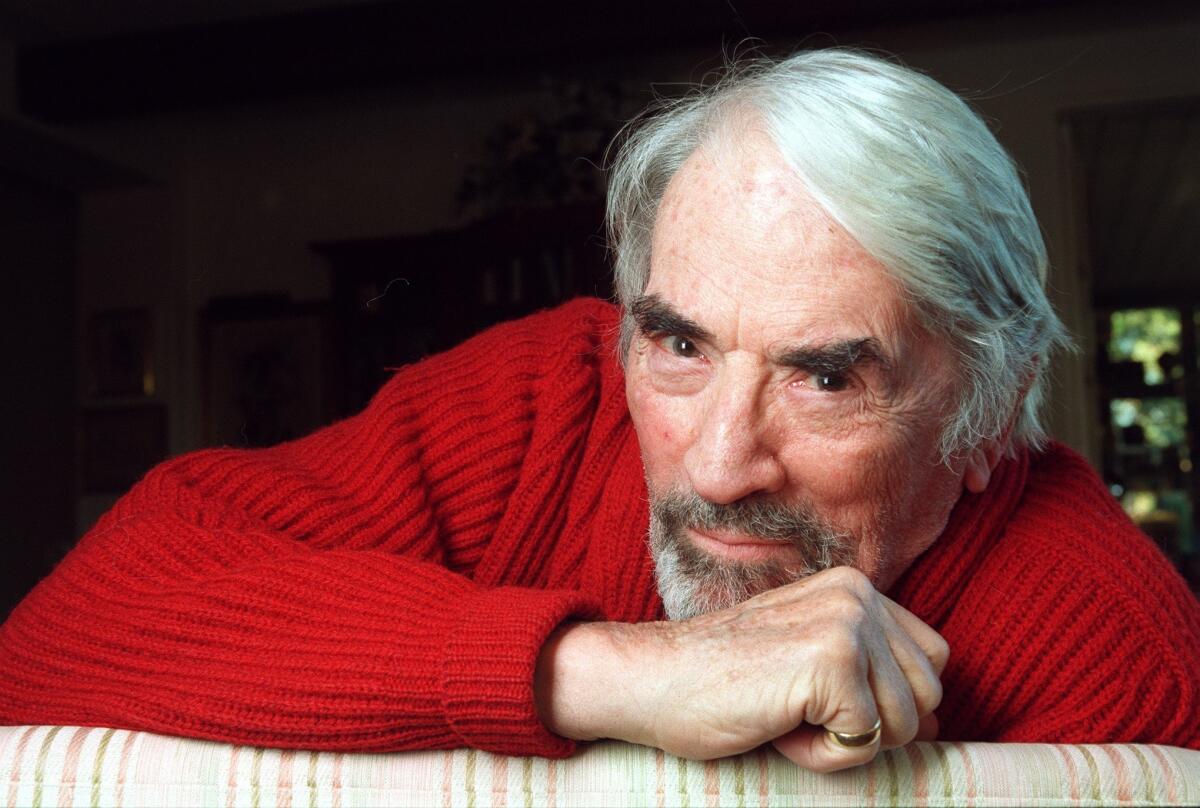

Actor Gregory Peck at his Beverly Hills home on Dec. 11, 1997.

- Share via

The publication last year of “Go Set a Watchman,” Harper Lee’s sequel to “To Kill a Mockingbird,” shocked fans of her classic novel for portraying the heroic Atticus Finch as a bigot. But that revelation hasn’t tarnished the power of the lovely, sentimental 1962 film version that starred Gregory Peck in his iconic Oscar-winning role as the Southern attorney defending an African American man (Brock Peters) accused of raping a white woman. The film also featured the lyrical narration of Kim Stanley and memorable performances from young Mary Badham as Atticus’ daughter Scout, which earned her an Oscar nomination for supporting actress; Phillip Alford as his son Jem and Robert Duvall as the strange Boo Radley, who comes to the children’s rescue.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

“To Kill a Mockingbird” earned eight Oscar nominations. Besides Peck’s lead actor Oscar, the film won adapted screenplay honors for Horton Foote and art direction.

ABC aired the classic on Christmas in 1997. And Susan King sat down with Peck, then 81, to discuss his experiences making the film and his relationship with Lee, who died at the age of 89.

Move over, George Bailey; Atticus Finch is joining the ranks of beloved Christmas classics. ABC has decided to air the beloved 1962 drama “To Kill a Mockingbird,” starring Gregory Peck as Atticus, Christmas evening and is considering making it an annual holiday event.

Atticus, for whose portrayal Peck won a best actor Oscar, is, as in Harper Lee’s novel, a widower living in the racially divided town of Macomb County, Ala., in the early 1930s, father to 10-year-old Jem (Philip Alford) and 6-year-old tomboy Scout (Mary Badham), the film’s narrator.

Racial tensions erupt when Atticus agrees to defend an honorable black family man (Brock Peters) accused of raping and beating the daughter (Collin Wilcox) of white-trash bigot Bob Ewell (James Anderson).

Produced by Alan J. Pakula and directed by Robert Mulligan, the nostalgic drama also features Robert Duvall in his film debut as the mysterious Boo Radley. Kim Stanley narrates as the adult Scout. Horton Foote won the Oscar for his screenplay and Elmer Bernstein supplied the haunting score.

Over the past 50 years, Peck, 81, has given acclaimed performances in such legendary films as “Keys of the Kingdom,” “Spellbound,” “The Yearling,” “The Gunfighter,” “12 O’Clock High,” “Roman Holiday” and “The Guns of Navarone.” Though usually cast as honorable men, Peck did play his share of “scalawags,” as he describes them, including the wild Lewt in “Duel in the Sun.”

In person, Peck is charm personified--everything you’d hope the man who brought Atticus to life would be like. On a recent sunny afternoon, Peck reminisced about “To Kill a Mockingbird” and Atticus--his favorite role, he says--in the comfortable sitting room of his expansive Beverly Hills house, which he shares with his wife of 42 years, Veronique. Peck’s beloved Maltese, Lulu, was sleeping at his feet.

Throughout the interview, the music of Bob Dylan played away on the stereo. (It so happens that Peck pays tribute to Dylan, whom he’s admired for 25 years, on CBS’ “The Kennedy Center Honors: A Tribute to the Performing Arts,” airing Friday.)

You must be thrilled ABC is airing “To Kill a Mockingbird” on Christmas night.

There seems to be a lot of genuine enthusiasm about it. There is sort of murmuring about it becoming a perennial on ABC, which is a good thing.

You know that it’s shown in all the middle schools. Hardly a day passes if I walk out on the street somewhere, someone--a parent or maybe a grandparent--is almost sure to say, “Oh, my 14-year-old son, daughter or grandson read the book and saw the movie in class.”

I heard about one not long ago. I guess the teacher asked them to write an answer to the question: “What was your favorite scene in the movie?” So this boy, 14, wrote, “I like the scene where Bob Ewell spit in Atticus’ face.” That got my attention!

I read on and it turned out what he said was, “I knew that Atticus could have clobbered Bob Ewell, but he didn’t because his son was sitting there in the old car watching and he wanted to set a good example for his kid.”

[Atticus] had told him in the picture that, “I don’t want you to fight because there is going to be controversy. Kids at school will call you names and maybe they will pick a fight”--so the kid came to the conclusion that I was setting a good example for my boy. He got the whole point of it.

The movie is my little pipeline to an entirely other generation.

Did you have any idea that Atticus would become your signature role?

I didn’t know that. Mulligan and Pakula acquired the film rights and sent me the novel. Other guys could have played it, but I’m so glad they thought of me first.

I read the book one night and I couldn’t wait to call them in the morning and tell them, “If you want me, I’d love to do it.”

It felt good while we made it. It seemed to just fall into place without stress or strain--the screenplay by Horton Foote was very well-written. When you have that kind of screenplay it becomes rather easy if you lend yourself to it and you go along and share the emotions with the character. You always have got to keep a clear head, of course. You can never get too emotional that you get foggy up there [points to his head]. You have to think your way through the part and identify emotionally with the situations and characters.

I remember seeing a rough cut. I usually have lots of suggestions and I like to write suggestions. I can badger a director or producer, and have many times, with suggestions for rewrites and certainly suggestions for editing.

So I trot in there with my yellow legal pad and I watched about 15 minutes and I just flipped the pad in the air. I didn’t want to make any notes. Bob and Alan laughed.

You don’t see many characters as noble and courageous on screen these days as Atticus is. Why do you think there are more antiheroes now?

It reflects the world we live in. We see a lot of mayhem and ugliness [on TV]. We have an instant window on the world. It seems to be there is more anger in the world. The result is they are not writing heroic characters or romantic characters or idealistic stories. Now and then something will come out, like “Schindler’s List.” But there were pictures [in the past] that portrayed courageousness, bravery, intelligence. It almost sounds like an Eagle Scout oath, but there were more [heroic] characters on the screen that Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda and other people were playing.

Is it true that you identified with Scout and Jem because life in that small Alabama town reminded you of growing up in La Jolla?

Definitely. La Jolla was maybe 1,800 to 2,000 people, so you knew everybody. At that time the houses didn’t have addresses, they had names. Sometimes sort of cutesy names like the Do Drop Inn. We had treehouses in the summertime like the kids in “Mockingbird.” I remember you would curl inside of an old rubber tire and some other little kid would give you a push and you’d roll down the street--[Jem and Scout] did that in “Mockingbird.” So the general tone of life there was similar to what Harper Lee was talking about.

I know you’re still in touch with Philip Alford [now a contractor living in Birmingham, Ala.] and Mary Badham [a housewife living near Richmond, Va.], but are you also friends with Harper Lee?

I talk to her half a dozen times a year and when Veronique and I are in New York and she’s there, we see her and have lunch with her.

Didn’t she give you the pocket watch belonging to her father--on whom she based the character of Atticus--after he died?

Yes. I met her father before he died; he died before the picture came out. I had the watch in my vest pocket for the Oscars in ’63. I also had a rabbit’s foot from my little girl. So I had these tokens to see me through.

But I had bad luck with it. We traveled from here to London to Nice on our way back to the south of France. When I got to Nice [I discovered] a black case that I had with bronze metal hinges and a lock had a rope tied around it and the locks were broken. The watch had been stolen by luggage thieves at Heathrow.

I was reluctant to tell Harper. I thought this was a precious thing. Her father had carried it in the courtroom for 30-odd years. He had a habit of fiddling with it and I stole that mannerism from him in the film. I fiddled with my watch during the courtroom scenes.

But she said, “Well, it’s only a watch.” Harper--she feels deeply, but she’s not a sentimental person about things.

Was there ever discussion of a sequel to “Mockingbird”?

Oh, God, no! We are all resolved not to allow it to be colorized--not to allow a sequel. Harper, Bob, Alan and I actually own the film. Universal only distributes it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.