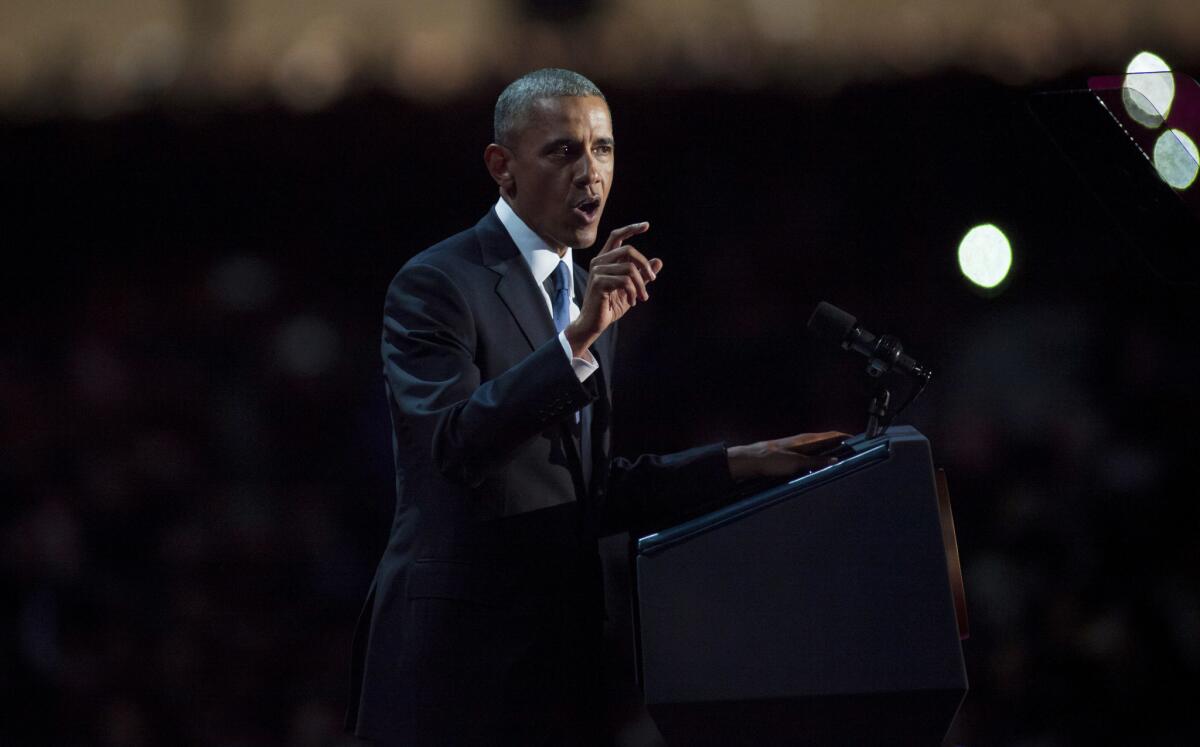

Eloquence and literary power make President Obama one of the nation’s great orators

Moments after he was elected as the country’s first black president in 2008, Barack Obama stepped on a Chicago stage and mingled poetry with optimism, praising Americans who were not afraid to “put their hands on the arc of history and bend it once more toward the hope of a better day.”

Whether as candidate or president, Obama knew it came down to words, the way they spun and gathered, lifted and fell on precise beats with restrained flourish. From the moment he electrified the Democratic National Convention in 2004 until his farewell address Tuesday night, his speeches streamed from an eloquent inner voice that could lay bare the vestiges of racism and mourn with a nation stricken by gun violence and the graves of children.

Obama’s legislative legacy may be in jeopardy from President-elect Donald Trump, but the grace of his prose will endure. A gifted writer, Obama understood the power of words to elicit images and rouse passions in settings from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., to the banks of the Nile in Cairo. His sentences soothed and stung, coaxed and challenged, drawing fits from his critics while urging his supporters to seek moral and political transcendence.

His cadence and description created pictures. In his 2009 eulogy for Edward M. Kennedy, Obama seemed to channel F. Scott Fitzgerald, saying the enduring image left by the senator was “of a man on a boat; white mane tousled; smiling broadly as he sails into the wind, ready for whatever storms may come.”

“Barack Obama is one of the great orators in American history,” says Douglas Brinkley, a presidential historian and professor at Rice University. “He thinks in constitutional law terms that give him the spine for his speeches, his compass.” More so than other presidents, he adds, “Obama consistently wanted to feel he was the author.”

His flowing discourse, which softened the dispassionate and cerebral view many had of him, stands in vivid contrast Trump’s staccato clauses and Twitter bursts. The nation’s narrative in coming years will change not only politically but also poetically in how our essences are framed and our meanings distilled. One need only compare Obama’s lyrical memoir “Dreams From My Father” with Trump’s “How to Get Rich” to know that a brash and bare-knuckled lexicon is rumbling up from Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach.

A country’s identity is the fusing of millions of disparate stories into a singular vision. Obama told many of those stories, as a young, lanky senator, and as a graying, embattled leader with a growing list of anecdotes gleaned from everyday Americans that were at once quiet in their humility and resounding in their resolve.

His mastery of syntax and delivery is reminiscent of presidents Kennedy, Reagan and Clinton. But the soul of his sentences -- the resonance, depth and musicality – hark back to Abraham Lincoln and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., with a bit of Nelson Mandela’s sparse stoicism stirred in. These men and their voices played into Obama’s deep sense of U.S. history and his belief in the promise of democracy, which he succinctly summed up in the phrase: “in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.”

Like Reagan and Roosevelt, Obama used his words and manner to calm the nation in tragedy, notably after the mass shootings that plagued his presidency. The day of the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, which killed 20 children and six adult staff in 2012, he appeared on TV, wiping tears from the corners of his eyes. At a prayer vigil with parents days later, Obama, a father of two daughters, spoke of how futile words were at fathoming grief and loss.

“I come to offer the love and prayers of a nation,” he said. “I am very mindful that mere words cannot match the depths of your sorrow, nor can they heal your wounded hearts. I can only hope it helps for you to know that you’re not alone in your grief, that our world too has been torn apart, that all across this land of ours, we have wept with you. We’ve pulled our children tight.”

Obama entered talking. He skyrocketed to prominence after his keynote speech, titled “The Audacity of Hope,” upstaged both John Kerry, the presidential nominee, and Clinton, the consummate storyteller, at the National Democratic Convention in 2004.

Four years later, he was the president. It was clear from the beginning that Obama, a meticulous re-writer and editor, was in control of his language even as he brought on talented speechwriters including Jon Favreau, who could slip into and articulate his views.

“I’ve never worked for a politician who values words as much as the president does,” Obama senior advisor David Axelrod told The Times in 2009. “The speechwriter is an unusually important person in the operation. [Obama’s] willingness to entrust his words to others is limited, and he wants to make sure the people who do write for him have an appreciation for how he thinks and how he wants to be presented.”

Obama’s speeches “were compelling and inspiring,” says Robert Dallek, a presidential historian and author of “An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963.” “I’d rate him pretty high an as orator. Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln were very impressive, and so were Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy, who had a kind of literary flair. Obama stands in that tradition in using poetry, literature and phrasing that is artistic.”

Dallek adds, however, that “I don’t know if there’s a single line in an Obama speech that will resonate through history.” He was referring to Kennedy’s inaugural address in which he said, “ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country,” and Roosevelt’s words during the Great Depression: “The only thing we have to fear is … fear itself.”

Obama’s most delicate use of language came when discussing race. As the nation’s first black president, the son of a white mother and an African father, he was sensitive (some would say overly) about addressing the country’s persistent racial problems. But in a eulogy in Charleston, S.C., after a white gunman killed nine worshipers at a church in 2015, he spoke of renewal and redemption and, emulating the best African American preachers, sang “Amazing Grace.” In Selma months earlier, Obama commemorated the 1965 civil rights march over the Pettus bridge by exploring the sins of the past but also extolling the progress made since the Jim Crow era.

One of his most memorable speeches on race — “A More Perfect Union” — was given during his 2008 campaign after excerpts from sermons by his pastor and friend Jeremiah Wright were publicized. Wright, who is also black, blamed the U.S. for its racism, its treatment of Native Americans and, borrowing a quoting from Malcolm X, said that the 9/11 attacks were a sign that “America’s chickens are coming home to roost.”

Obama was urged to disavow Wright, and he later resigned from the minister’s church following other controversial statements by Wright. But he initially responded with comments only a man of his background could have uttered, words that encompassed not only American history but also his own life in that wider, often troubling, story:

“I can no more disown him [Wright] than I can disown the black community. I can no more disown him than I can disown my white grandmother, a woman who helped raise me, a woman who sacrificed again and again for me, a woman who loves me as much as she loves anything in this world, but a woman who once confessed her fear of black men who passed her by on the street, and who on more than one occasion has uttered racial or ethnic stereotypes that made me cringe.

“These people are part of me. And they are part of America, this country that I love.”

To be sure, there were times “when his rhetorical gifts failed him,” as E.J. Dionne Jr. and Joy-Ann Reid write in their in the introduction to “We Are the Change We Seek,” a collection of Obama speeches published this month by Bloomsbury. “He was remarkably (and, to his supporters, surprisingly) ineffective in making the case for two of his major achievements, the economic stimulus and the health care program that bears his name. These failures haunted him throughout the presidency.”

But that was not the case during his farewell address in Chicago on Tuesday, when he called for unity and optimism to counter economic injustice, racism and our battered and divisive politics:

“I am asking you to hold fast to that faith written into our founding documents; that idea whispered by slaves and abolitionists; that spirit sung by immigrants and homesteaders and those who marched for justice; that creed reaffirmed by those who planted flags from foreign battlefields to the surface of the moon; a creed at the core of every American whose story is not yet written: Yes, we can. Yes, we did.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.