Salman Rushdie steps from behind alias

- Share via

Salman Rushdie is a selfless defender of artistic freedom. No, he’s really a party animal with a bombshell perpetually on his arm. Actually, he’s hiding in fear. Isn’t he?

For the last 23 years he’s been a novelist living the life of a character in a novel. Unfortunately for Rushdie, the book he’s been transported into isn’t a nuanced work of art like, say, “Midnight’s Children,” the epic novel that helped make his reputation as one of the best British writers of his generation.

It’s more like “a bad Rushdie novel,” he told me as we sat in the restaurant of a West Hollywood hotel. “The kind of book I’d write if I weren’t any good.”

QUIZ: Salman Rushdie’s not-so-hidden life

In 1989 the Iranian cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini declared a fatwa promising eternal life for any believer who assassinated Rushdie as punishment for the perceived blasphemies of his novel “The Satanic Verses.”

His Japanese translator was murdered, and another translator and his Norwegian publisher suffered bloody attacks. Across the Islamic world protesters were killed at violent, anti-Rushdie demonstrations. Rushdie would spend the next decade in a kind of self-imposed house arrest, protected by an around-the-clock armed police escort, living in assorted farmhouses in the English countryside and London apartments.

Now his clandestine life is a distant memory. When I meet him he’s in Los Angeles to see television people and is on his way to the Telluride Film Festival. His only protection at the London Hotel comes from an earnest young man in a blazer with a name tag that reads SECURITY.

“People think, ‘How odd it is that he goes out,’” Rushdie said. “Because for a long time they had this image of me as sealed away from life.”

After my interview with him, in the wake of rioting provoked by an anti-Islamic video, an Iranian foundation reportedly announced an increase in its reward for Rushdie’s murder. The news barely phased him.

“I’m not inclined to magnify this ugly bit of headline grabbing by paying it much attention,” he said via his publisher.

Death sentences aside, today Rushdie lives in another kind of bubble: the one where the tabloids turn your life into a kind of running joke. Even the august New York Times recently got into the act, recounting his seemingly nonstop appearances at Manhattan galleries and the various beauties in his orbit. “From Exile to Everywhere,” the headline ran.

This is a strange way for a distinguished man of letters to be living. To be under the microscope not for what you write but for the way you live.

“It makes me out to be some sort of ridiculous party animal,” he said of these stories.

How Rushdie managed to get himself into successive bubbles is the subject of his new memoir, “Joseph Anton” (Random House, 636 pp., $30), a title that comes from the code name he gave himself while under the protection of British police.

“Joseph Anton” is written in the third person. It reads as if Salman Rushdie were writing a novel about a character named Salman Rushdie.

“He had spent his life naming fictional characters,” Rushdie writes in “Joseph Anton,” recounting the moment when Rushdie chooses his code name, derived from the first names of two of his favorite writers, Conrad and Chekhov. “Now by naming himself he had turned himself into a kind of fictional character as well.”

Why did Rushdie write a kind of nonfiction novel about Rushdie? For a decade after his ordeal had ended, he said, “the last thing I wanted to do was go back … into the emotion and darkness of that time.” But he never doubted he would tap into his experiences one day. “Even when things are at their worst,” he says, “there’s a little voice in your head saying, ‘Good story!’”

He said his initial attempts to write the book as a first-person memoir sounded “self-regarding,” “narcissistic” and too much like a journal or a rant. But “Joseph Anton” can’t help but be a bit of all those things.

It’s an angry retort to those who tried to silence him, especially the British Muslim leaders who took up the anti-Rushdie cause. And it’s self-regarding in its minute description of Rushdie’s life in hiding — an all-star team of British literati make cameos in its pages, including Harold Pinter and Graham Greene.

But beyond all that, “Joseph Anton” is also a gripping, firsthand account of an important battle for artistic freedom. If radicals could force two of the biggest publishers in Britain and the U.S. to cease publication of a novelist’s work, who else could they silence?

“Joseph Anton” also turns out to be a fascinating character study. In hiding Rushdie never stopped being his flawed, idiosyncratic self. He confesses in “Joseph Anton” that he wants to be liked — even by his enemies. Imagine a man with a target on his back whose burning desire is that you like him.

In “Joseph Anton,” Rushdie, like a good novelist, delves into the past of his main character. He came of age in the intellectual firmament of 1960s and ‘70s London, a bright and oddball Indian immigrant. He was ambitious and found literary fame with “Midnight’s Children,” a tale set against the backdrop of Indian independence.

In the 1988 novel “The Satanic Verses” Rushdie took on questions about the history of Islam that his Muslim-raised father often pondered when Salman was growing up in Mumbai. No one — not Rushdie, or his editors — expected that doing so would set off a murderous firestorm.

“It wasn’t just me that was naive,” he said. “Everyone was.”

In hiding, the contradictions in Rushdie’s life only sharpened. He was an exceedingly sociable man trapped in a clandestine life with a second wife, Marianne Wiggins, who was realizing after just a year of marriage that she really didn’t like him much. And also with a group of sharp-shooting British police officers with nicknames like Fat Jack.

Despite the security bubble around him, Rushdie met and married Elizabeth West, a young woman from the publishing world who’s portrayed in “Joseph Anton” as a quiet and loyal partner. They had a son. But in 2004 Rushdie left her for the statuesque Padma Lakshmi. “You saw an illusion and you destroyed your family for it,” West tells Rushdie in “Joseph Anton.”

Rushdie makes it clear he feels like a fool for falling for the future star of “Top Chef.” “Nobody’s perfect,” he said, impishly.

His time in hiding ended when the Iranian government announced in 1998 that it would no longer seek to carry out the fatwa. Now he lives in New York City. He takes the subway as if no one had ever proclaimed a death sentence against him and makes himself accessible to 400,000 followers via Twitter, where he once composed a limerick about Kim Kardashian.

He’s been married four times, but he takes issue with the stories that make him out to be a Don Juan or a Casanova. Most of the women photographed alongside him with the words “striking” or “beauty” in the caption are just friends, Rushdie said, insisting he’s far from the one-dimensional lech that tabloids make him out to be.

“People construct these selves for well-known people,” he said. “And those selves acquire a kind of credibility by repetition.”

None of those stories ever points out, he noted, that he helped start a book festival in New York, PEN World Voices, that’s now in its eighth year. Or that, as director of PEN Center USA, he helped defend many writers who were under threat.

For the moment, Rushdie is not ready to embark on another novel. Instead, he’s writing a television pilot for Showtime, a sci-fi drama called “Next People.”

As for “The Satanic Verses,” it’s still in print, in 46 languages, a small victory in an ongoing battle.

“On the one side there’s almost everything I value most: liberty, art, imaginative freedom, tolerance. And on the other side there’s bigotry, intolerance, violence, a kind of religious fascism,” Rushdie said. “The battle chose me, I didn’t choose it.”

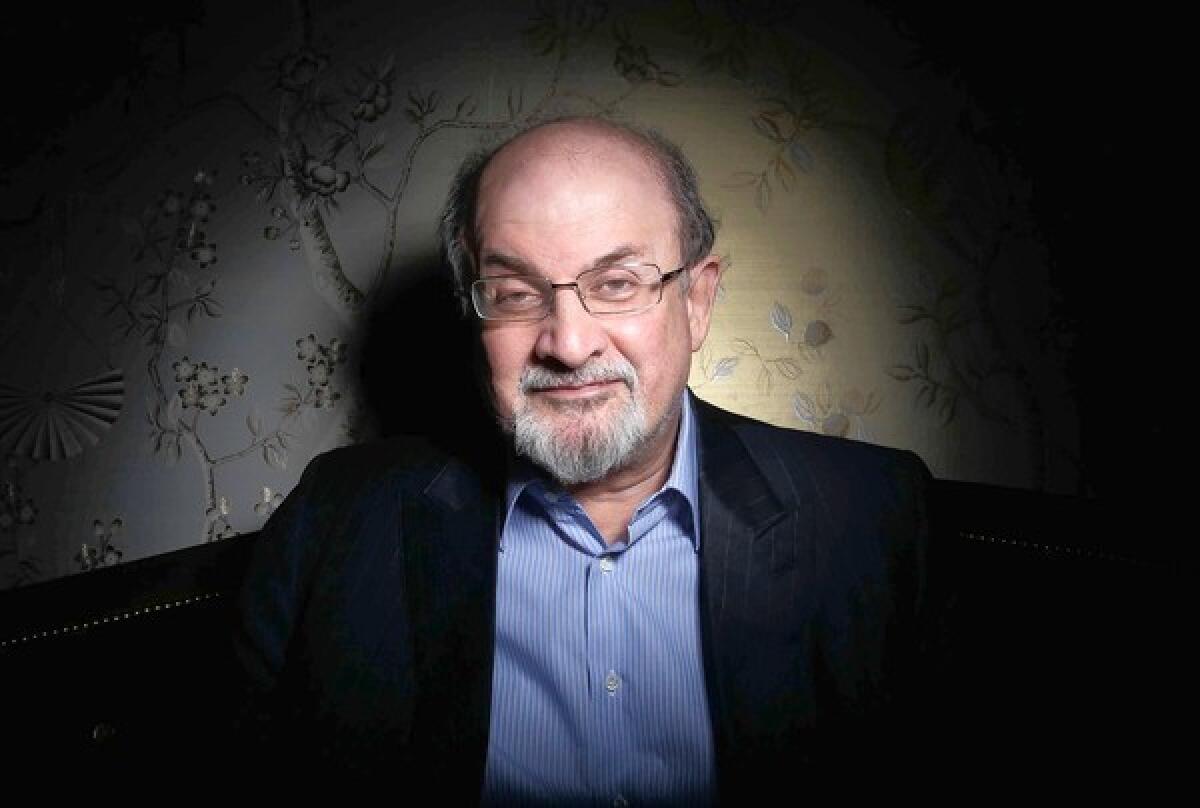

A few moments later, Rushdie, the author and imperfect defender of literary freedom, posed in the London Hotel for a few more photographs for this article. Then he was off to Telluride to see his new film. More critics and cameras awaited him.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.