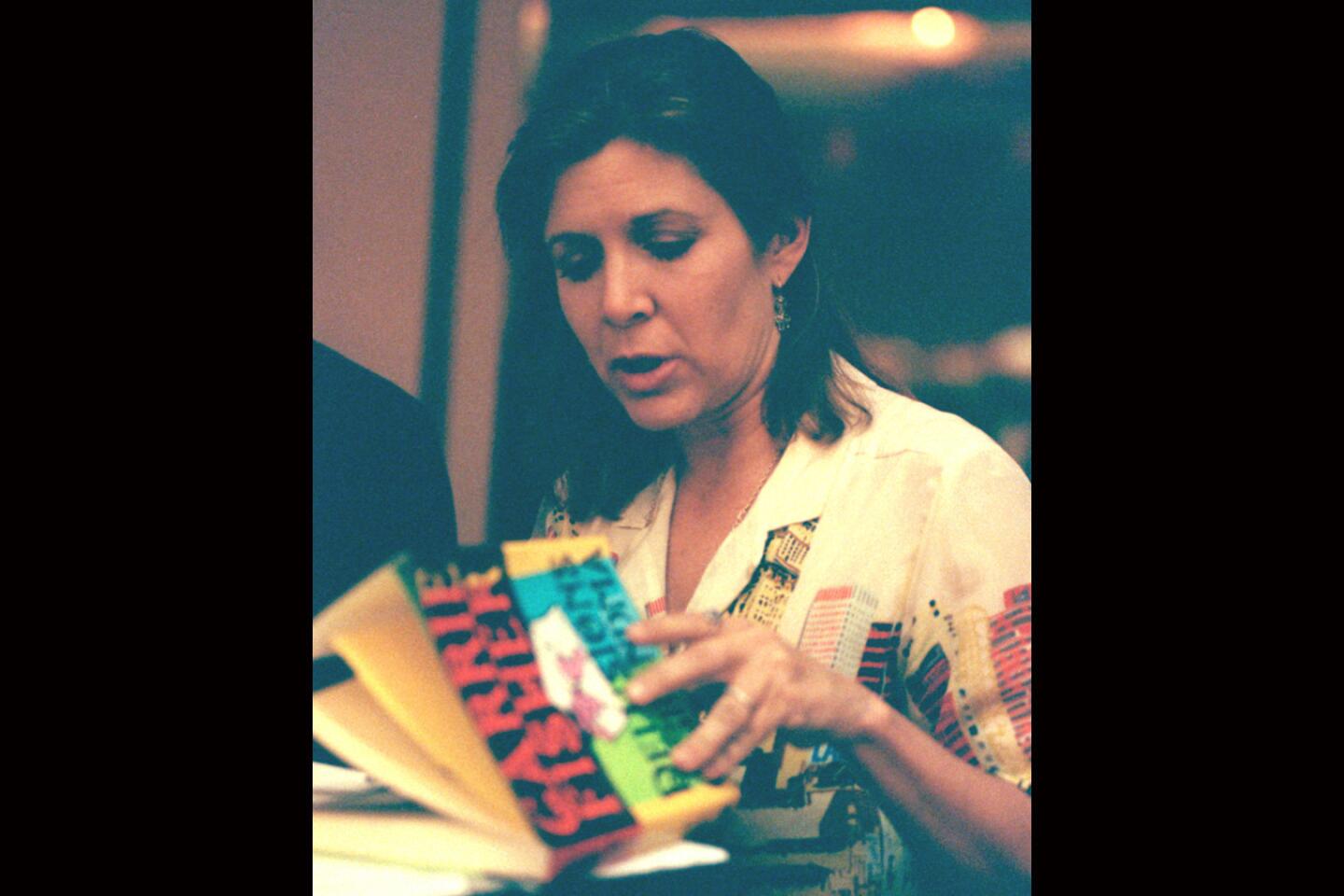

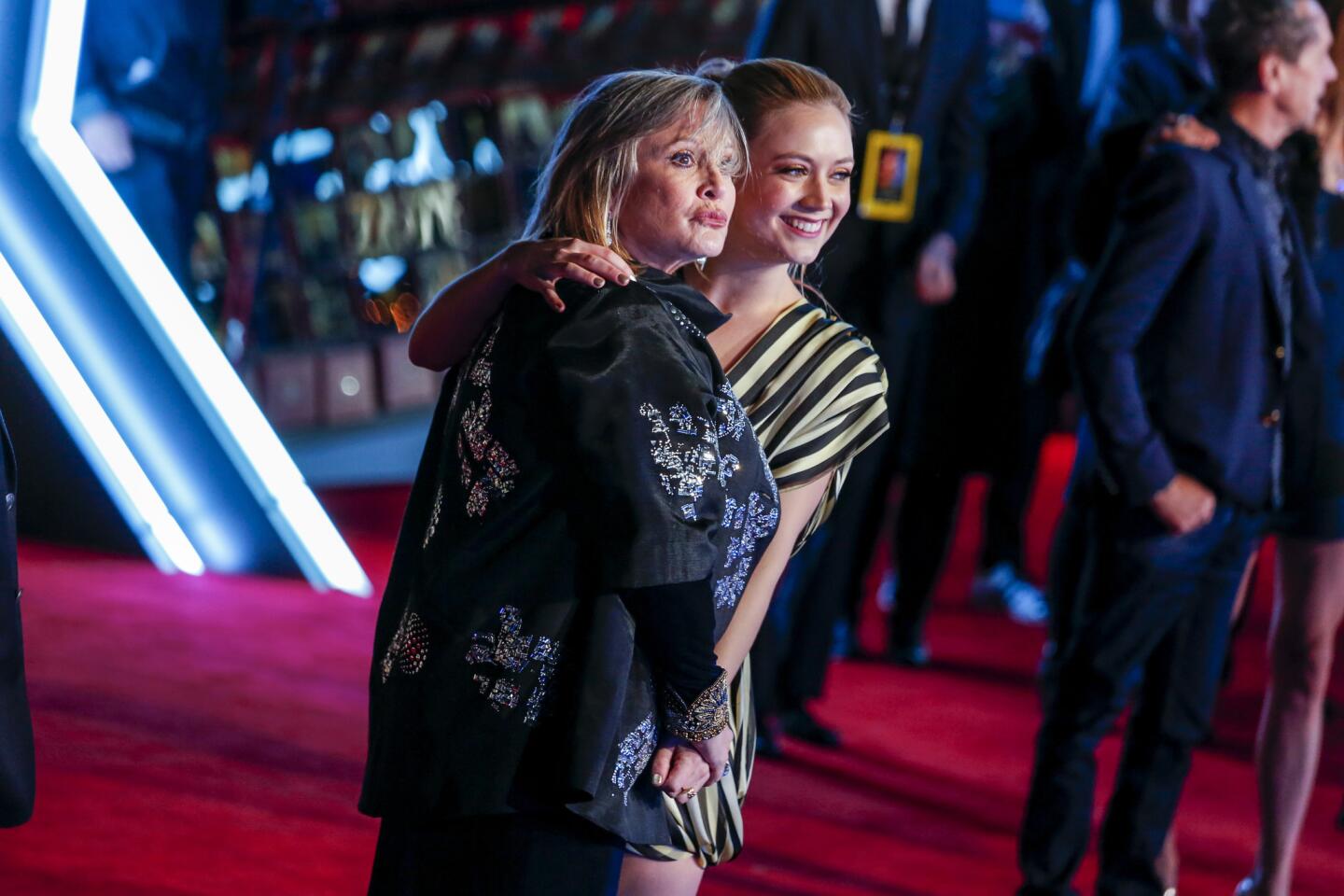

From the Archives: Q&A: Debbie Reynolds and Carrie Fisher discuss Hollywood families, not-so-fictional novels — and baby Billie’s there to chaperone

Carrie Fisher, the child of two Hollywood icons and who rose to fame as Princess Leia of the blockbuster “Star Wars” series, has died at the age of 60. The Los Angeles Times interviewed Fisher and her mother, actress Debbie Reynolds, who died the day after Fisher, in 1994 about Hollywood families and Fisher’s autobiographical novel. This article was originally published on April 24, 1994:

“Is something burning?”

From the moment Debbie Reynolds pads into her daughter’s cathedral-sized living room, carrying a large kitchen knife and sniffing the air, you know you’ve entered the house of mirth a la Carrie Fisher. Of course, there are plenty of clues outdoors: the Santa and reindeer on the lawn, two plastic beef carcasses leaning against the fence and all those signs — No Vacancy, Lover’s Lane, That Very Evening — not to mention Fisher herself, scampering down the path, barefoot, in wet hair and a floor-length panne velvet dress. The house is famous — Edith Head and Bette Davis each called this rambling, Spanish-style ranch house home before Fisher bought it last year — but now it is the distinct province of the 37-year-old writer and sometime actress who is Hollywood’s de facto Dorothy Parker.

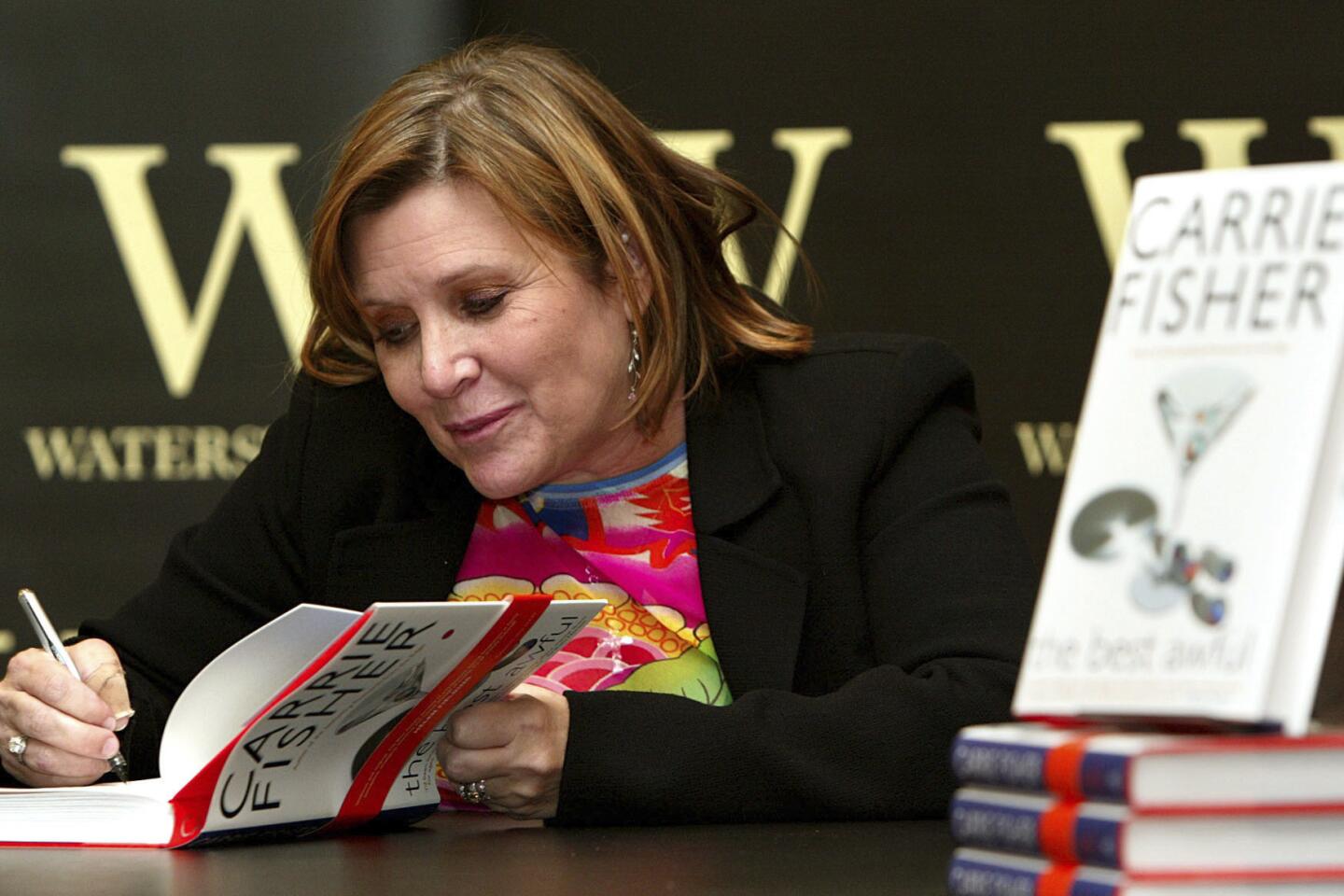

Fisher comes from Hollywood royalty — Reynolds and Eddie Fisher — but she has made her own mark in town as a script doctor and novelist. Steven Spielberg hired her to buff Tinkerbell’s lines in “Hook.” Whoopi Goldberg brought her on board to polish “Sister Act.” Fisher’s first two books, “Postcards From the Edge” and “Surrender the Pink,” were best-selling chronicles of her life, her recovery from drug abuse and the breakup of her marriage to singer Paul Simon. Meryl Streep, Fisher’s close friend, starred in the 1990 film of “Postcards,” and Demi Moore is expected to star in “Surrender the Pink,” when Fisher completes a rewrite of the script.

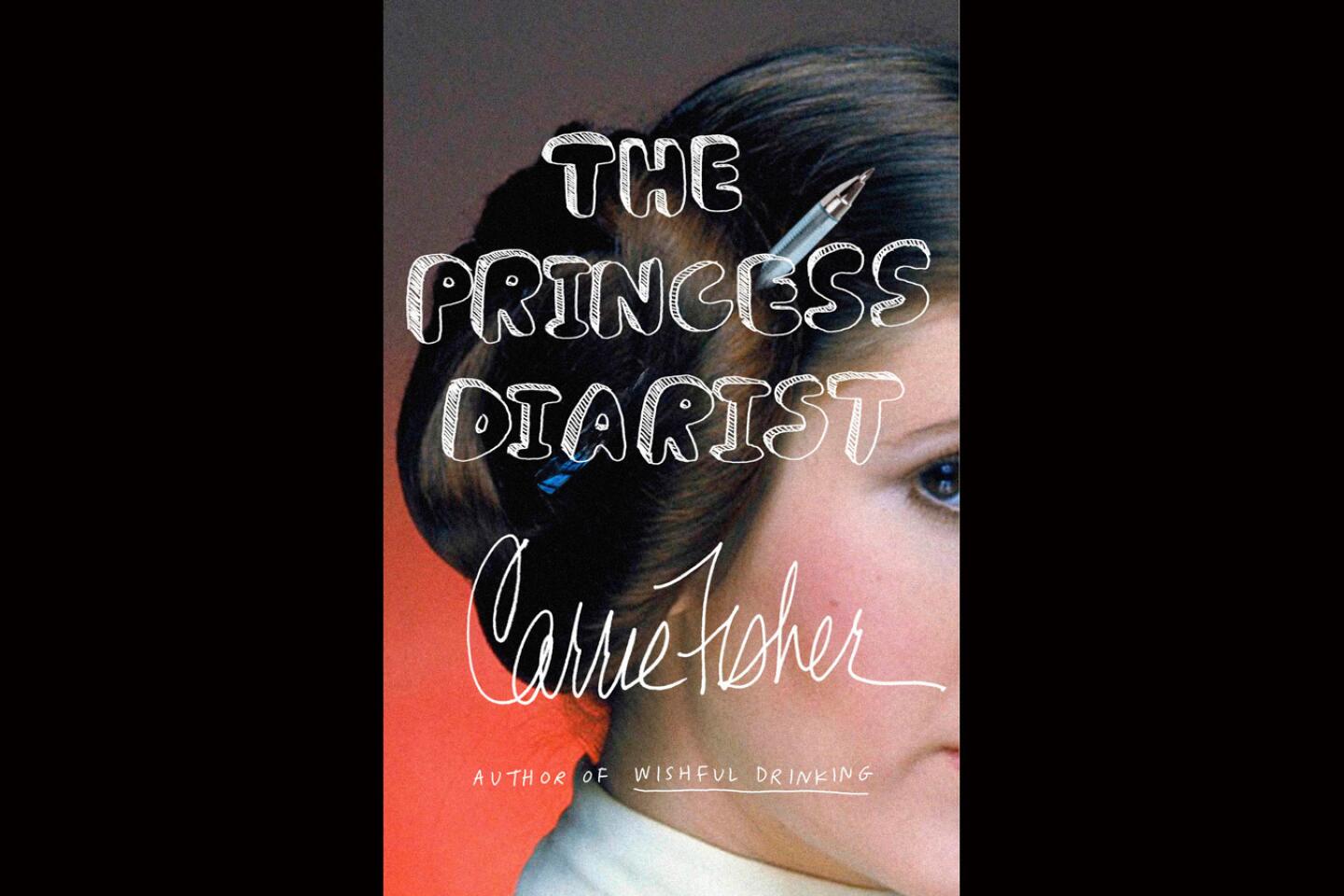

At the moment, Fisher is basking in the generally positive reviews for her autobiographical novel “Delusions of Grandma,” which charts the birth of her first child, Billie, and the breakup of her relationship with CAA agent Bryan Lourd. She is just days from leaving for Europe, more publicity for the book, and then a week visiting Gore Vidal on Italy’s Amalfi Coast. “I know the book jacket says I divide my time between Los Angeles and Florence,” she says in her famously throaty voice, “but I just made that up because it sounded so great.”

Fisher’s household resembles nothing so much as a hotel, filled as it is with animals (including a parrot), staff, family and friends. A three-way interview with her mother and daughter about their lives in Hollywood becomes a rambling, disjointed conversation that has as many exits and entrances as a bedroom farce. A carefully orchestrated photo shoot in the back yard — Fisher, Reynolds and squirming 20-month-old Billie in a hammock — becomes its own occasion for pratfalls when the hammock unceremoniously dumps all three to the ground. “OK, OK, we’re up,” says Reynolds, scrambling to her feet, her face as composed as a freshly smoothed pillow.

Eventually, Fisher retires to her bedroom, where beneath the deep-blue ceiling embellished with gold stars and moons she seems to find a soothing environment. Sitting cross-legged on her massive bed, alternately smoking and fingering raw brownie dough from a dish, she confides to being a little daunted by the challenges of being a single mother in Hollywood’s fast lane. Her frankest remarks about Lourd are made off the record — more sad than mean. By conversation’s end, Fisher is completely prone, under her expensive hand-embroidered French sheets, thoughtfully blowing smoke at the stars above her.

*

Carrie Fisher: You know, someone came in the other day and said, “Your house is so Catholic now. But that’s original (pointing to an antique-looking icon perched on a ledge up near the ceiling). It was Edith’s.

Debbie Reynolds: It’s Mission style.

CF: I wouldn’t mind being Catholic, because they seem to get over things really quickly — they go to church, they sing, they confess. Or they become Madonna and go on TV and say [expletive] 13 times.

DR: Now, you’re not making fun of Catholicism, you just like the objects. People are so sensitive about their religion, I don’t want the press to think —

CF: No, I’m saying it would be good to be Catholic. I was raised Protestant but I’m half Jewish — the wrong half. They got ticked off in Israel when I went there with Paul [Simon] and we had gotten married by an Orthodox rabbi and I hadn’t converted.

DR: You have to convert to make the Orthodox happy.

CF: How long does that take?

DR: Only eight weeks, it’s not a long booking.

CF: Well, how long does it take to become a Catholic, so you can go into that box and say I did this stuff and now I’m sorry?

Q: Doesn’t writing thinly veiled autobiographical novels serve the same function?

CF: It’s like AA — you get up and say things about yourself; I don’t consider it confession, but it’s acknowledging. You act like yourself, and after you’ve done it for so long, you become who you think you are.

*

Q: This novel seems fairly revealing of your private life. Doesn’t writing about yourself, even in fictional form, affect you?

CF: Well, this book prolonged the difficulty of my separation [from Lourd], because it held my attention to it — that I have a child with someone who is not around, and I’m sorry to be in that situation because I know what it’s like to be that child. But it’s the first book I wrote while I had a child, and a child really changes things. Over Christmas when I was editing the galleys, I couldn’t pay that much attention to her, and she got pissed off — at four months! So finally I just said, “Take the book.”

*

Q: Debbie, how has having Carrie’s first child — and her writing about it so publicly — changed your daughter? The title refers to you.

DR: Carrie really wanted this baby. She’s wanted one since she was 11, when I was going to give away all her baby clothes and she came in and said, “Well, what will my baby wear?”

*

Q: Yet Carrie, you lead a very public life. You also grew up with a very public mother who worked a lot.

CF: Did you ever meet anyone who said, “I had the greatest childhood”? Yes, I worried that I would neglect her at close range, because I am a working mother. I know that she will feel somewhat neglected, but she really won’t be aware of it until she gets to be 13 or 14 — that’s when I got very resentful of my mother’s work. But I also have an obligation to a mortgage.

*

Q: There were some difficult times in your life, Debbie, when your second marriage (to businessman Harry Karl) ended and you had to go out on the road to support Carrie and Todd.

DR: When Carrie was 14, my second husband lost all his money and all my money. We started over again and he hit the road. And it was hard for Carrie when I had to devote so much time to work and not enough to her and she got angry with me, and she didn’t understand —

CF: — how tough it was for her at 38 to fall out of a marriage and lose all her money. I can appreciate it now, but when I was 14 I got very arrogant, because I had gone through est or something. And she had also lost two children — two children born dead.

(She gets up.)

I’m having a cigarette.

DR: (after Carrie leaves for the front porch) But anyway, all that hurt Carrie’s growth at a very tender age. Finally we found a psychiatrist, when she was 15, and I think that helped her a great deal. After she grew up, she found out I was OK.

CF: (yelling from the porch) My fear is that I will be crushed in an elevator and my mother will get hold of my journals from my adolescence.

*

Q: (as Carrie re-enters the room) Do you think the two of you are alike? Your public personas are so wildly different.

CF: I think we are — the energy I have comes from her.

*

Q: What about your satirical side?

CF: Not in the same way. But she uses her Tammyness to great effect — she works against it and is able to be audacious in the darnedest ways.

DR: Both Carrie and I have strong, definite personalities — I’m a true Aries, and she’s a true Libra. I was never frightened of being in front of an audience; Carrie is much shyer.

*

Q: Did you feel inadequate compared to your mother’s fame and beauty?

CF: Not the fame part, but the beauty. I would see her after parties looking perfectly pulled together. That scene that I put in the book, when Cora tries on her mother’s wedding dress, was actually Mom’s wig. (To her mother) Do you remember? I was in your dressing room, and I put it on thinking maybe this will do it for me, and I looked like a thumb.

DR: You thought you would be transformed into a blue-eyed blonde.

*

Q: What about Billie? Are there similarities there?

CF: We are all bossy. (To Debbie) Grandmother is extremely bossy, you are, I am and now Billie is. This is what she says: “No work”; “Get off the phone”; “Come play.”

DR: I think she’s very bright, like Carrie. Very demanding, wants attention, is very spoiled — and Carrie is all of that. She talked at 6 months.

*

Q: But you successfully convinced (Carrie) to go to drama school in London, which led to her career as an actress.

DR: As a rule I gave in to her, but this was too much. We had played the Palladium in London when Carrie was 17, and we did three performances together and Carrie just killed them. The reviews said, “Debbie Reynolds is the gold of vaudeville, and she has brought us the platinum.”

CF: I thought that meant I was bad. But then I figured out what platinum meant and I thought I could become like Liza Minnelli.

DR: But while we were in England, she had also auditioned for the Central Drama School, and she got a scholarship.

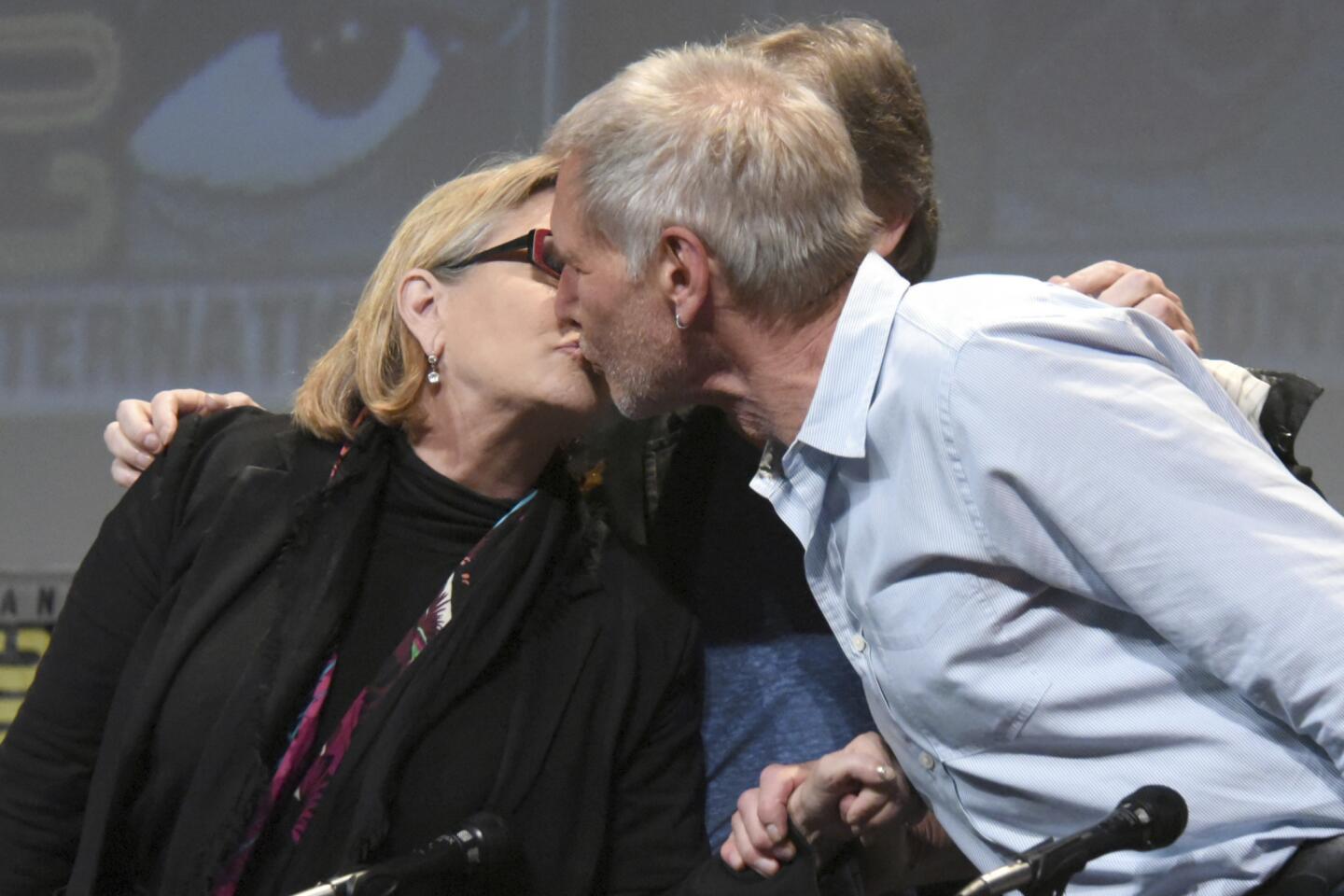

CF: Then I left because I got “Star Wars.”

*

Q: Carrie, can you talk about that quality of being observed — it seems to be in your style of humor as well, the art of the put-down.

CF: I always felt that we were being looked at: “She’s Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher’s daughter, and she thinks she’s so special.” So I wanted to be able to walk in and say, “I’m so fast you don’t have time to think it.”

DR: Carrie has definite problems putting herself down. She is the most attractive —

CF: She always tells me, “Don’t be so hard on yourself, dear,” like it’s something you can just go, “Oh, OK, thank you for reminding me, I’ll stop now.” ... It’s that Jewish Angst thing.

DR: I’m not going to comment on that. We’ve already hit the Catholics.

Q: Isn’t some of that just endemic to growing up in Hollywood?

CF: Yeah, people think you have it so great. But I wanted to be like everybody else; in order to fit in, I put myself down.

DR: I’m not as nervous about myself because I wasn’t brought up in the business. I had a normal life; we didn’t meet movie stars. We lived in Texas where you had rollerskates and if you got a bicycle that was a very big gift.

CF: (picking at her fingernails) I felt disadvantaged by my advantages.

DR: She peels them down to blood.

CF: I can’t help it; I’m just finishing this one nail. I just quit smoking because I got pneumonia, but like Mark Twain says, “I quit as easily as I start,” and —

DR: Honey, your eye ...

CF: Is it all falling down? The bleeding eye. It’s those talk shows. When I looked at the tapes of myself, I thought my arms looked like blood sausages.

DR: You see, she doesn’t need a critic.

CF: I have one: Ralph Novak at People magazine, remember? He wrote about my first book: “Darth Vadar should have killed her when he had the chance.” ...

(She gets up.)

Excuse me, I’m going to go check on the toasting of Billie. She’s napping, or what I call “browning on two sides.”

*

Q: In her novel, Carrie attributes several negative attitudes toward men to the mother’s numerous marriages. Do you take any of that personally, Debbie?

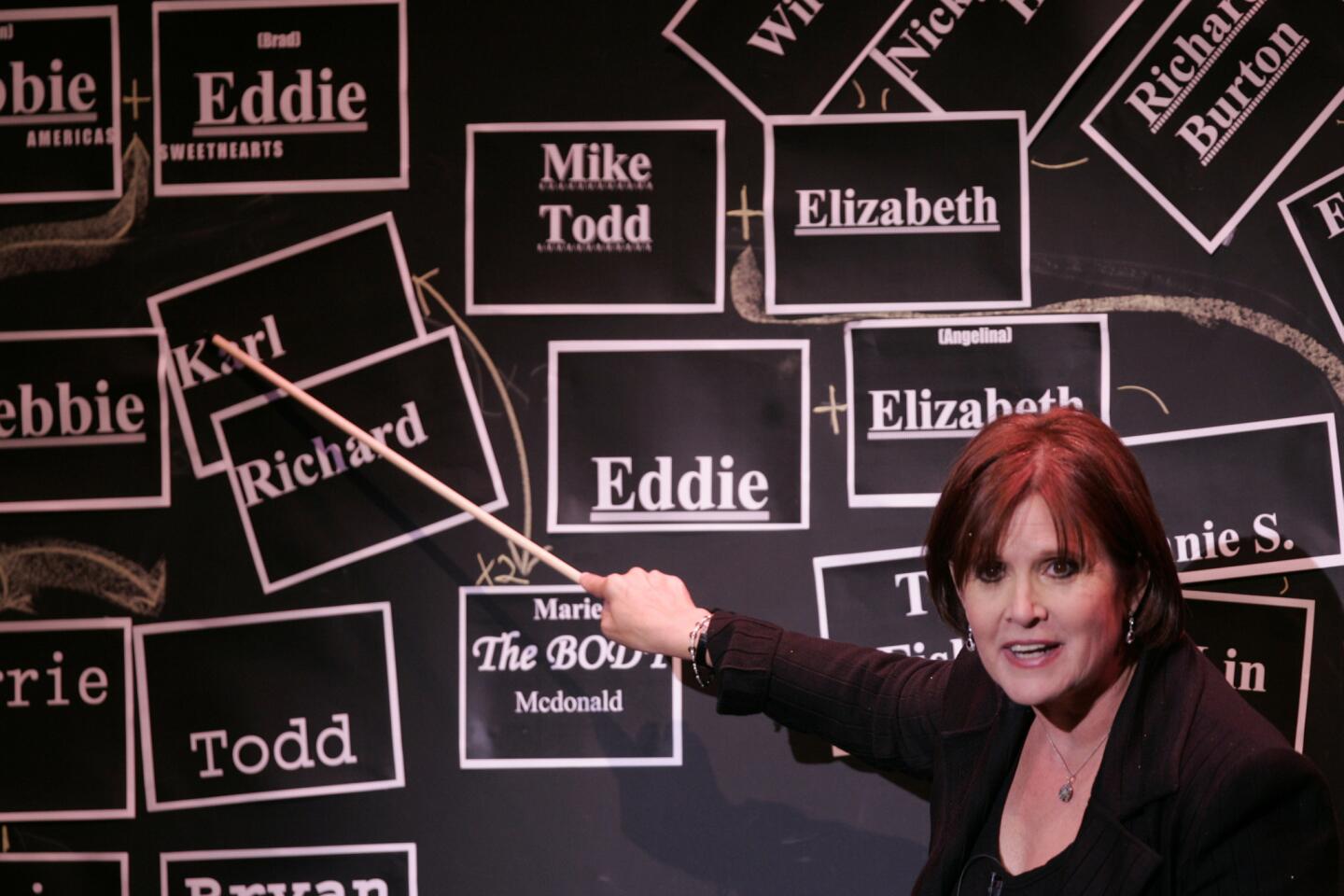

DR: I was married to Eddie Fisher when I was 22, and he left when Carrie was a year and a half. Then I was married to Harry Karl, who was 25 years older than myself because I wanted someone who would take care of us. I was married 14 years to him. I remarried 10 years ago, but now I’m separated — another crisis. So I’m not one to advise about marriage. I should see a board of directors who should vote on who I should date.

*

Q: How do you feel about Carrie’s situation, being a single mother of a young child?

DR: I’m always sad to see a relationship not work, but what happens between two people is not my business. I feel very happy she has the baby. I just don’t think marriage is in the cards — for Carrie or me.

*

Q: Do you think it’s harder to maintain a relationship in Hollywood?

DR: I just think it’s hard for all women who are powerful or out front with themselves. Men can find beautiful young ladies who don’t mind walking in their shadow because they can shop on Rodeo Drive.

(Carrie re-enters with Billie, the nanny, who carries a child-sized plate of food, and various assistants in tow.)

DR: There she is! She’s a happy girl now.

CF: (starting to feed her) We’re having sweet potato.

Billie: (screaming) Nooooo!

CF: OK, OK, OK — let me get it out. We used to like sweet potato. Come on, give us the smile you did when Mickey Mouse came to visit one weekend and sang “Happy Birthday” by mistake. ... Come on, Billie, show everybody how pretty your eyes are.

BL: (screaming) Nooooo!

CF: They’re more green than mine are, more like the father —

DR: — son and Holy Ghost.

CF: I was going to say, the father has blue eyes.

*

(Later, after Reynolds has left for the airport, Fisher holds court in her bedroom — cigarettes, a Coke and her dish of brownie dough at her side.)

CF: I gained so much weight with the baby, I said I looked like a frying pan with features.

*

Q: Did you hide from all your famous friends?

CF: Oh, yeah, I had most of my relationships on the phone. I was so embarrassed because I realized how much I depended on at least a modicum of good looks. Even though I’ll say I don’t like my looks, I was sure I was somewhat attractive. So there I was thinking, well, I’ve had a kid, and this is old age for me. It wasn’t until Bryan and I had the split-up that I lost like 20 pounds in two weeks, which was the only good thing about it.

*

Q: You’ve been so unstinting in condemning Hollywood for making it difficult to achieve an equal relationship —

CF: — and if you’re more powerful than they are you’re emasculating them. And I’m not revising that. I only hope I’m wrong. But also, I do have this big loud life, and so the other person has to crawl in there and find some peace. Even when I was with Paul, he liked more privacy than me; we’d go off to Montauk for the weekend, and Ed Begley Jr. would call, and that was a big deal, like, “Why is Ed Begley calling?”

*

Q: Why do you gravitate toward groups so much? You once said that you like to be ‘the mayor of the group.”

CF: I have smart friends. My biggest fear is that everyone is going to move to New York after the earthquake. (David) Geffen told me he might move, and Meryl is going to go back, and Buck Henry already spends a lot of time in New York.

*

Q: Even your screenwriting is personal: You wrote a pilot that was based on you and your mother’s relationship, and the new TV series you’re writing for Carsey-Warner is about you to some extent.

CF: The character is like me, but you know, this whole house could be a series. During the fires last fall, singer Patti Smith, who lives in Topanga, moved in here with her daughter and a dog and a cat and two mice, and we lived in this room. We watched the TV for the fire updates to see if her house had burned, and we called it “Fire Watch: The Series.”

*

Q: What’s next for you?

CF: What I want to do doesn’t matter because I have to service my overhead, which is enormous. I still own my other house, which I bought for $1 million and I can’t rent because it got damaged in the earthquake. And I bought this house for $2.5 million so I’m like —

*

Q: Nervous?

CF: Bryan and I split Billie’s care, but there are other issues, like I moved into this house thinking we would be here together — we decorated it together — and now you could argue that since he left, I should sell it. But I think I’m going to try it.

*

Q: Your salary on script-doctoring has been pegged at about $100,000 a week.

CF: But you don’t get those all the time, and I only just did my first one in almost two years — for Michael Caton-Jones — because of the baby and the book. It’s great, but now I have to do it.

*

Q: Have you considered writing more of your own scripts and think about moving into directing, as Penny Marshall and Nora Ephron have?

CF: Oh, man. Nora’s kids are older, and she’s married, and she didn’t do that until she was 50. So maybe I could when I’m 50. How old would Billie be? 14? Yeah, I could do it — but I would like to have another child. I think the easiest thing to do would be to have it with a friend. I suggested it to Albert (Brooks), and I told him between the two of us a bolt of lightning would come out between my legs.

*

Q: Is marriage out of the question?

CF: I thought when we had a child together that was more than married. Albert was saying to me, “Who are the models we can look at and say, ‘That’s a great marriage’?” Tom and Rita Hanks have a great relationship. Maybe I can just get into theirs.

*

Q: You’re joking, but it also sounds like you’re genuinely disappointed.

CF: I was genuinely happy when I conceived, and I thought at that point we were going to make it. (Lourd) comes from a background of great stability, and he presented himself as very reliable and straightforward. But coming up against my life. ... The one thing I ended up coming away with is that if you want to be in a relationship, everything is negotiable — and ought to be, if you have a child.

Billie spends Wednesday and Friday nights with Bryan, and I think it’s important because I didn’t see my father a lot.

*

Q: He always seems mentioned, like part of your resume.

CF: Yeah, but would I go to my father for advice? No. Well, maybe about kicking drugs or something.

*

Q: So there is something you want to give Billie that you didn’t have?

CF: A father — and that’s a big thing for me to give.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.