Book review: Luka and the Fire of Life by Salman Rushdie

- Share via

Luka and the Fire of Life

A Novel

Salman Rushdie

Random House: 224 pp., $25

Once upon a time, in a literary galaxy in the distant past (say, the 1990s), before Harry the boy-wizard had expecto-ed his patronum and vanquished He Who Must Not Be Named But Was Anyway All The Time, when the word “vampire” put one in mind of Bela Lugosi and his leer instead of Robert Pattinson and his half-dead, half-bedroom eyes, it was possible for an author to use the phrase “world of magic” without provoking an inward groan.

It was possible to be quickened, enlightened and thrilled by José Arcadio Buendía and Gabriel García Márquez’s otherworldly history of his family, by Angela Carter’s crafty mysticism and by the sheepmen and weird subterranean creatures plaguing the weary, Chandleresque protagonists slogging through Haruki Murakami’s glittering but humdrum Tokyo.

It was even possible to devour, in one enraptured sitting, the not-quite-picaresque, not-quite-allegorical adventures of Salman Rushdie’s character Haroun, as he journeyed through not-quite- India rescuing a city from sadness. Alas, we no longer live in that galaxy, and when you read in Rushdie’s new novel, “Luka and the Fire of Life” that Haroun’s little brother Luka has “reached the age at which people from this family cross the border into the magical world,” and is growing giddy at the prospect of “an adventure of [his] very own,” you may well be tempted to emit such an inward groan.

Indeed, it may not be so inward. I did devour Haroun’s tale in such a world-obliterating sitting, and I find that certain images from “Midnight’s Children” and “The Moor’s Last Sigh” still shine in my literary memory, many years after first reading those novels (Rushdie’s two best, by far), and I still found it nearly impossible to race past the cloyingly false childishness, the canned sense of expectation that the first chapter sets up. Reader, persist. Rushdie may do bombast (“The Ground Beneath Her Feet”) and he may do overwritten (“The Enchantress of Florence”), but he does not do boring, and he knows his way around a good almost-myth.

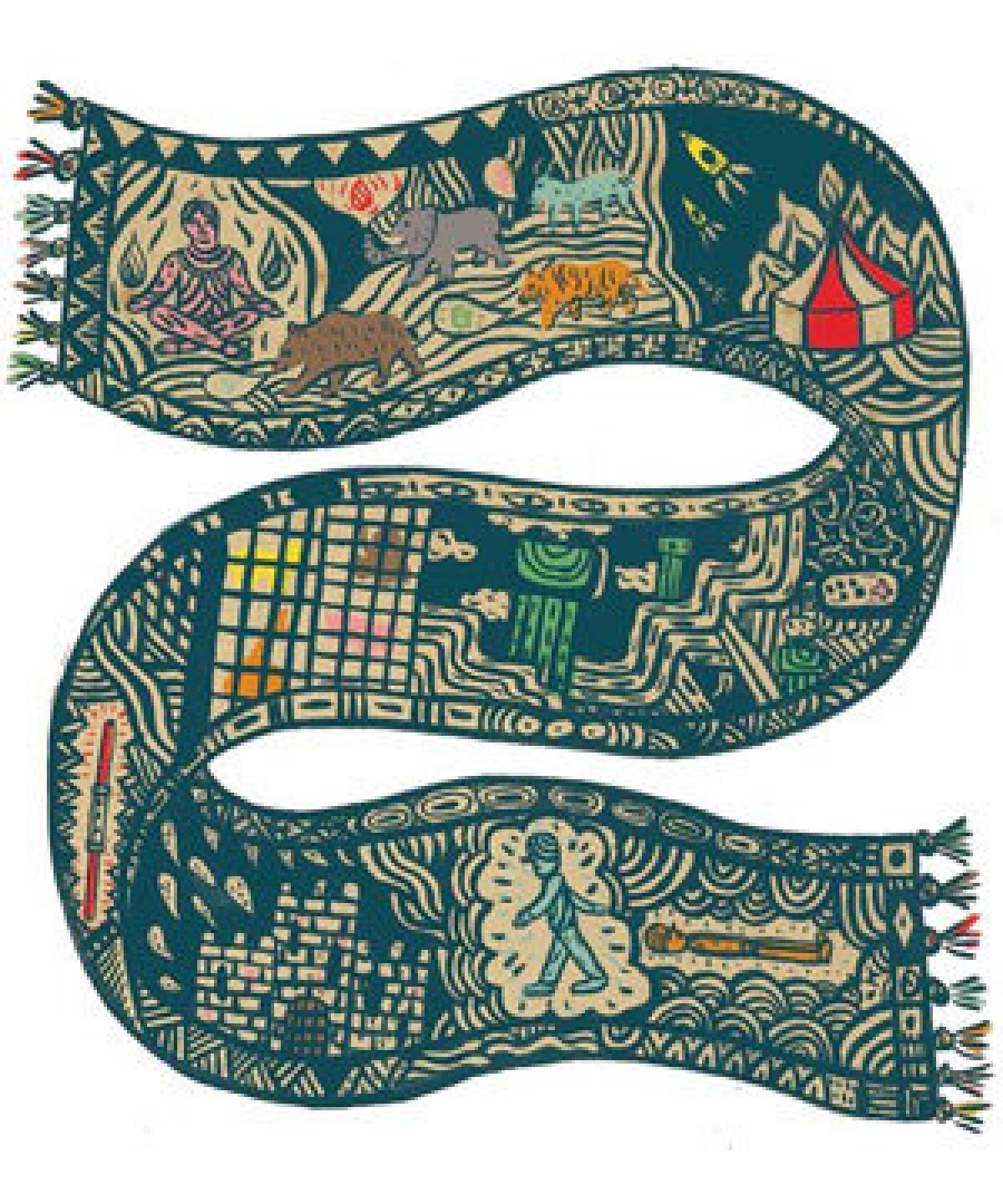

As with “Haroun and the Sea of Stories,” Rushdie wrote “Luka and the Fire of Life” for one of his sons, on the boy’s 12th birthday, and the book is best appreciated as a sort of adjectivally ‘roided-out fable, heavy on the cultural parallelism and light on the religious import. Like “Haroun,” which was published 20 years ago, “Luka” takes place on a fantasy plane that combines southern Asia, India and America, but its main influence is quite different. Twenty years ago, the average 12-year-old boy imbibed most of his stories through the television. Today he more likely gets them through video games. Rushdie, almost alone among modern fiction writers, gives these games their narrative due.

After all, what are video games if not stories in another form? (That idea is explored at length in Tom Bissell’s outstanding “Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter.”) And Luka, like so many children today, “lived in an age in which an almost infinite number of parallel realities had begun to be sold as toys. Like everyone he knew, he had grown up destroying fleets of invading rocket ships and been a little plumber on a journey through many bouncing, burning, twisted bubbling levels to rescue a prissy princess from a monster’s castle, and metamorphosed into a zooming hedgehog, and a streetfighter and a rockstar, and stood his ground undaunted in a hooded cloak while a demonic figure with stubby horns and a red-and-black face leapt around him slashing a double-ended lightsaber at his head.”

Rushdie’s novel progresses as a quest in much the same way as classic video games. (Here some age-centering is necessary: By “classic” I mean “Super Mario Brothers” and “Legend of Zelda,” which may tell you that I’m 35 years old. I left “Space Invaders” in the dust, have a glancing familiarity with “Sonic the Hedgehog” and never quite made it to “Halo.”)

One day, Luka, who comes from a magical family that not only includes Haroun but also his father, accomplished storyteller Rashid Khalifa, passes a circus and grows incensed by the caged animals. He curses Grandmaster Flame, the ringmaster: “May your animals stop obeying your commands and your rings of fire eat up your stupid tent.” That night, the animals stop performing and the circus burns down.

The curse works, but Grandmaster Flame sends a threatening letter, which coincides with Luka’s father having fallen into an extended sleep. Shortly thereafter Luka meets his father’s doppelgänger (“Nobodaddy”), whereupon he embarks on a quest to find the Fire of Life to waken him. Initially Luka dismisses said Fire as “just a story,” but Nobodaddy reminds him that is an unjust remark. “Man is the Storytelling Animal,” he tells him. “[I]n stories are his identity, his meaning and his lifeblood.… Man alone burns with books.” The who, what, where and when of this story are best left to the reader — recounting it would be as dull as, well, recounting progress in a video game. The story is in the why and the how, and it is well worth reading.

Fasman is the author of the novels “The Geographer’s Library” and “The Unpossessed City.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.