The Aztecs, through old-world eyes

A 1,200-pound stone head of an Aztec moon goddess has moved into the Getty Villa. So have life-size statues of a warrior adorned with eagle feathers, a duck-billed wind god and a demon known as the Lord of Death.

Made between 1440 and 1521 and on loan from Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology and the Templo Mayor Museum, the massive artworks are among 64 sculptures, paintings and works on paper in “The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire.” Opening Wednesday, it’s the most surprising exhibition yet to appear at Southern California’s bastion of classical Greek and Roman antiquities.

The Villa has raised eyebrows with temporary installations of contemporary art related to its collections and exhibitions. But Aztec art? At a museum devoted to art made many centuries earlier on the opposite side of the world?

“It’s probably not what you would have expected at the Getty Villa,” says Claire L. Lyons, the Getty’s antiquities curator who organized the show with John M.D. Pohl, a pre-Columbian specialist and research associate at UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. “But we have long been interested in expanding beyond the classical Mediterranean.” “In Search of Biblical Lands: Nineteenth-Century Photography of the Ancient Near East,” to appear in 2011, will explore historic sites and pastoral life on the eastern margins of the Mediterranean.

In “Aztec Pantheon,” with an eye on its Mexican American audience, the Getty is celebrating the bicentennial of Mexican independence by exploring how Europeans came to understand the Aztecs -- in terms of the Roman Empire. “From the moment Europeans went to Mexico, especially Spanish conquistadors who accompanied Hernán Cortés in 1519 and missionaries who arrived after the conquest, they encountered a culture that was so unfamiliar, the only frame of reference they had was their knowledge of Roman antiquity,” Lyons says. “Looking through that lens, they interpreted the Aztecs as the Romans of the New World.

“The idea that a faraway place is equivalent to a distant-in-time place is a very powerful metaphor,” she says, adding that the Maya have been compared to the ancient Greeks. And it had particular resonance at a time when Renaissance Europe was smitten with the rediscovery of classical antiquity. Literature of the period likened Mexico’s capital, Tenochtitlan, to Troy, Jerusalem and Carthage as well as Rome.

“The comparison guided how the Spanish crown came to grips with its role in the New World,” Lyons says. “It was used to justify the imperial mission but also to critique it. Spain itself had been a Roman province, so scholars and clerics could use the native Spanish oppression by the Romans to question what was taking place in the New World.”

Powerful sculptures

A group of monumental sculptures will be the visual power center of “Aztec Pantheon.” Compelling in artistry and imaginative expression as well as size, they have been plucked from places of honor in Mexico’s leading museums.

There’s an ancient fertility goddess made of wood and shell, a terra-cotta model of an Aztec temple and a statue of a priest wearing a human skin, also fashioned of terra cotta. Visitors will also find an elaborately carved funerary urn and a 3 1/2 -foot-tall incense burner bristling with agricultural cult images, including the goddess Chicomecoatl, who was compared to the Roman goddess Ceres.

As Bertina Olmeda, curator of the Aztec gallery at the National Museum of Anthropology, puts it: “The pieces that came here are of the first order.”

But the linchpin of the exhibition is a relatively modest illustrated book that usually resides in the Medici Library in Florence, Italy. “Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España,” better known as the Florentine Codex, is a sort of bible of a disappearing culture created in 1575-77 by Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar who taught Latin, rhetoric and Christian theology at a college in Mexico City.

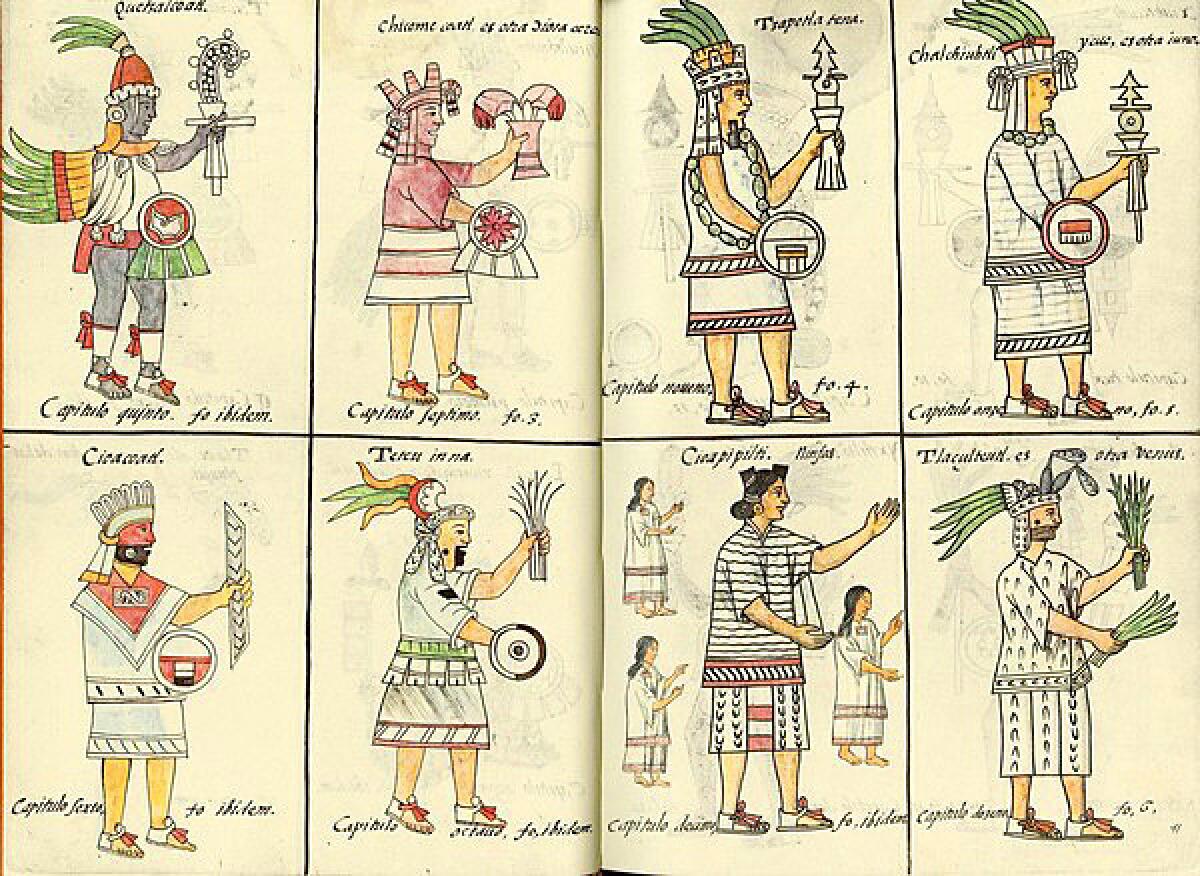

A bilingual description of the Aztecs, in Spanish and the local Nahuatl language, the Florentine Codex reflects the Spaniards’ effort to understand the Aztecs, the better to proselytize them. Although missionaries were expected to eradicate all traces of native religion and history, Sahagún set out to document every aspect of Aztec culture by interviewing the elders and persuading them to record their memories and make drawings in their pictograms.

The idea, Lyons says, was to learn enough about Mexico’s indigenous people to synthesize Christianity with Aztec beliefs. While the relatively open attitude prevailed, Sahagún’s students helped create a text that accompanies more than 2,400 images.

The book was sent to Spain during the Inquisition, when works written in indigenous languages were banned, and later given to the Medici Library. Largely forgotten until the early 19th century, it is available only to specialists and is seldom on public view. “It is an incredible thrill to be able to borrow this iconic work,” Lyons says. “This will be the first time it has returned to the New World.”

The book has been bound in three volumes. The Getty has borrowed the first volume, which will be open to watercolor illustrations of Aztec deities, some of whom are equated to their Roman counterparts. Huitzilopochtli is likened to Hercules, Tlaculteutl to Venus. Reproductions of other pages also will be displayed.

Lyons gives much of the credit for the genesis of the exhibition to Michael Brand, the director of the J. Paul Getty Museum who abruptly resigned in January, and Thomas Cummins, a Harvard University professor of pre-Columbian and Latin American colonial art and recent visiting scholar at the Getty Research Institute. “A kernel of an idea about parallel pantheons began to grow out of early conversations,” she says. “As John Pohl and I explored the concept, what emerged very quickly was an important but little known phenomenon.”

Despite a flood of requests for loans to exhibitions honoring Mexico’s bicentennial -- including “Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler,” recently at the British Museum in London, and “Olmec: Masterworks of Ancient Mexico,” coming to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in October -- the Getty got nearly everything it wanted from the Mexican museums and a few other sources.

The loans were essential to the exhibition, but 22 of the works on paper came from the Getty Research Institute. Many of them are part of the Gutierrez collection, acquired in 1984 from the late collector Tonatiuh Gutierrez. He had amassed a vast trove of research material for a book on the early history and discovery of the Americas.

If Europeans based their knowledge on some of the exhibited prints, they must have had a fanciful, even bizarre, view of Mexico’s civilization. One engraving transforms the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli into a winged Satan with a feather headdress and a hairy animal’s legs. An encyclopedia of world faiths portrays human sacrifice at Tenochtitlan’s Great Temple, with one victim being slain on a platform atop skull-covered walls and another rolling down a steep staircase.

The Getty also has contributed a few Roman bronze objects “to spark ideas,” Lyons says. “We don’t want people to think there’s a relationship or an influence across thousands of miles and 1,500 years.” The point is to compare similar forms and subjects through the ages.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.