Q&A: Photographers Harry Gamboa Jr. and Luis Garza on pushing back against ‘bad hombre’ Chicano stereotypes

March has been a bit of an unofficial Chicano history month in Los Angeles.

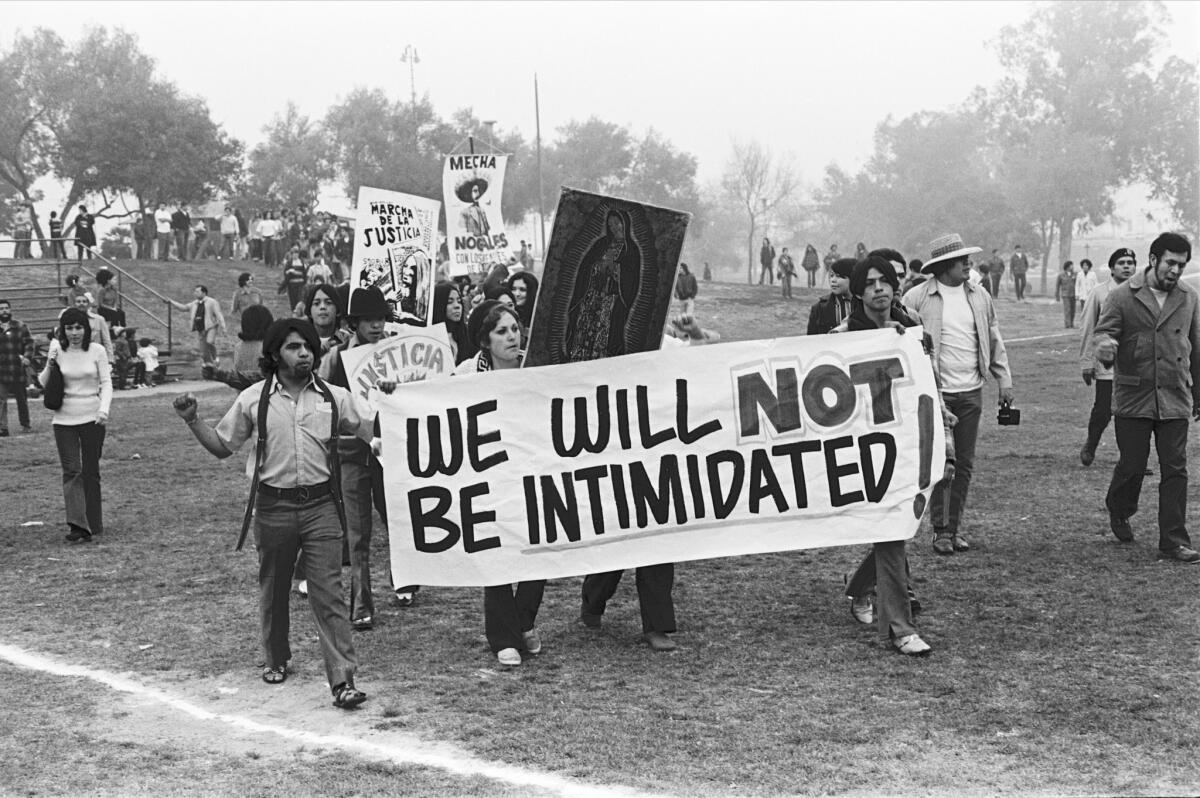

It began with the 50th anniversary of the East Los Angeles “blowouts,” the school walkouts led by Mexican American students that helped ignite the Chicano movement. It continues with the Friday debut on PBS of “The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo,” the first film on the life of Oscar “Zeta” Acosta, the often outrageous activist lawyer who defended some of the protest’s principal organizers.

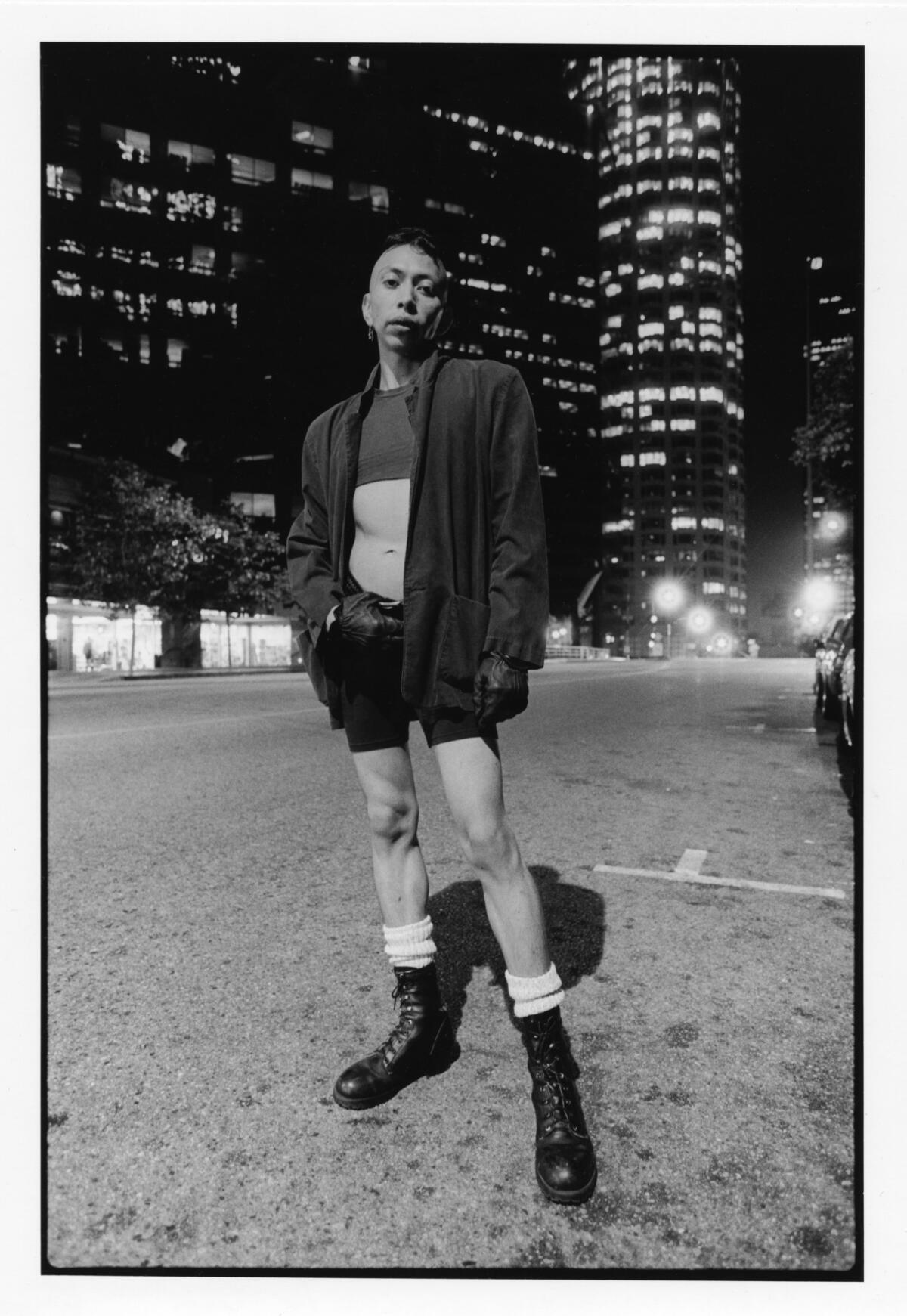

Meanwhile, a pair of exhibitions at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles explore Chicano history and identity: “La Raza,” organized by Luis C. Garza as part of the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA series of exhibitions, gathers photography and other ephemera from the pages of the 1960s-era activist newspaper. And Harry Gamboa Jr.’s installation, “Chicano Male Unbonded” — 84 photographic portraits of Chicano men who have affected his life — explores representation issues and webs of connection.

The shows tell a wildly different story about Mexican Americans than the political punch lines you might hear about bad hombres in the news. They document activism, faith, community and culture. Gamboa’s installation in fact, reads like a map to the region’s Chicanerati — the Chicano literati.

Garza, a curator and photojournalist, and Gamboa, a conceptual artist who is a founding member of the influential collective Asco, recently came together at the Autry to discuss issues related to Chicano identity. In this lightly edited conversation, they chat about the ways in which photography was used to create a counter-narrative, about identity and representation, and how their respective exhibitions kick back at all the stereotypes.

Luis, you covered the blowouts, and Harry, you took part in them. What has it been like to watch the current wave of school walkouts?

Gamboa: The walkouts of ’68 were a life or death situation. Young men were being drafted. We wanted to promote better education. But it required people to perhaps suffer the consequences of police brutality or being denounced in class. In the current era, you also have a life or death situation: where students are being sacrificed for the profits of the gun industry. That’s unconscionable. Any other country would take care of its children. That was our argument then.

Garza: It’s a pushback that is occurring in so many different forms — be it these walkouts, or the women’s marches, or Black Lives Matter. I see time bending in. When I look at 50 years ago and I look at now, I see a wrinkle in time.

Gamboa: Maybe one or two extra wrinkles [laughs] — and they are all well deserved!

Luis, how did you select the work you wanted to feature from the vast La Raza archive?

Garza: The La Raza collection now stands about 26,000 images — negatives dating from 1967 to 1977, which was the life of the publication. Some depict major events like the East L.A. walkouts or Aug. 29 [the 1970 Chicano Moratorium protest against the Vietnam War]. But there was daily life, too. There were children and families. There were people, their art, their food.

I went through several thousand images for the show because we didn’t have access to the entire 26,000 immediately since they were being digitized. It was a difficult process. We selected 250 photographic images, thereabouts, that are on the gallery walls. Other images are loaded into touchscreen computers. And within the show itself, it’s more than just photographs, it’s the graphic artwork, too.

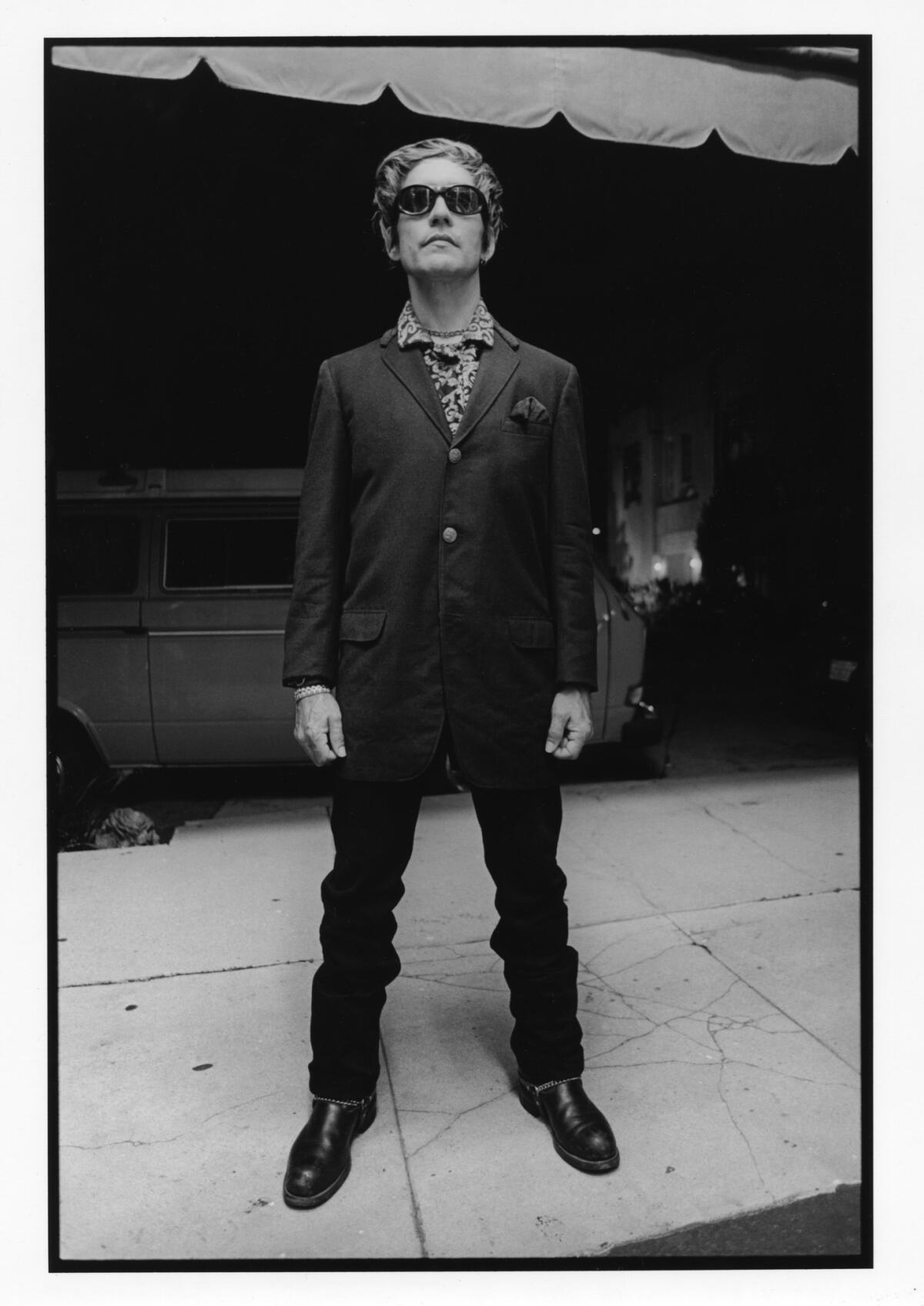

Harry, what are the origins of “Chicano Male Unbonded”?

Gamboa: I remember there was a preliminary meeting for the creation of the “Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation” show [a 1990 Chicano art exhibition at UCLA’s Wight Art Gallery]. I happened to attend a dinner where I was surrounded by artists and historians. Everything sounded so positive. When I got to my car to go back to East L.A., where I was living at the time, I turned on the radio — and it warned to be on the lookout for a Chicano male. It was this promotion of a negative stereotype.

I thought of all the males I knew who had influenced me: scholars, writers, poets, artists, family members. And I thought it’d be interesting to photograph the men I knew who had influenced me. I was going to photograph them at night. I wanted to make it film noir-ish. And Chicano men, when they’re shown in media, it was often askance or in a mugshot. I wanted to do it so that the men were looking down at you. It was to generate some anxiety in the viewer because this would likely be the first time a Chicano would look down on them.

This is a political moment in which Mexican and Mexican American men have been depicted as “rapists” and gang members. How does your work contend with how Chicanos are seen in our society?

Gamboa: The major event that contributes to Trump denouncing Mexicans is the vast vacuum that exists, the lack of a multitude of representations of Chicanos and Chicanas. This allows people to insert negative ideas into the vacuum. And this justifies the mean-spirited behavior on behalf of our government.

Garza: Our exhibition is a counterpoint. It’s a pushback. It’s an exploration of our humanity in general — of Latinos. My work begins with my family when I first pick up a camera and I start capturing my family and my environment in the South Bronx. (My family comes from Mexico, the south Texas area, but they migrate to New York in the 1920s.) And I’m brought up in a very diverse community and I begin to capture that. And then I come here in the mid-1960s and I become involved with La Raza and I am introduced to a whole new world.

You look at the collection and you see the expanse that the photographers cover. There are people in Harry’s collection that were part of La Raza. That’s the interesting thing about this project. It traces a genealogy. You see how it intersects with the arts community, academic community, with artists, musicians.

Gamboa: I knew people who had been involved in La Raza and they influenced me. I was the editor of a Chicano magazine called Regeneración. That’s how Asco started. I invited Willie [Herrón], then Gronk [Glugio Nicandro] and Patssi [Valdez] to participate. It all introduced me to ideas of media and counter-media. Mainstream media insists on a vacuum, but there is no vacuum. That required us to generate our own media. And this predates the internet, so it’s graphics, fliers, photographs. Asco was our foray into interrupting some of this. And a lot of it was in response to this insistence to remove the Chicano from the conversation. That persists today.

The lack of a multitude of representations of Chicanos and Chicanas — this allows people to insert negative ideas into the vacuum.

— Harry Gamboa Jr., artist

What significance would you say photography had to the Chicano movement and to Chicano art?

Gamboa: I’m born in 1951 — when they initiated the first nuclear test in Nevada, which means I was born at the onset of post-Modernism, and this notion that things needed to be deconstructed, re-evaluated and re-defined. The focus at the time would have been the language of cinema, which requires a great amount of funds. Cinema, however, is a sequence of stills. I decided early on to simply take a photograph. That became the “No Movie,” [Asco’s send-up of film stills]. Stylistically it could be at the same level of anything you could find in any magazine or any film. It would engage in conversation with multi-million dollar productions, but it would come from East L.A. for zero budget. Photography wasn’t cheap, but it was accessible.

Garza: That’s where La Raza as an organizing tool and informational tool begins — with photography. Photography was one of the arrows, along with poetry, along with cartoons, along with journalism. La Raza emerges out of this sense of frustration and futility, in challenging the system so you can be heard.

There was hard-core photographic work. The collection is part of a larger civil rights movement going on with the country at the time. We cover police brutality, indigenous rights, Catholic issues — all things that continue to this day. And people see their reflection, they are identifying with themselves. And it’s not just the Latino community, but a larger community. Why? Because the power of the photograph speaks to the humanity in us all.

Aquí estamos — en frente. That is the statement. That is the stand that we take. And it’s a stand that has a long history.

— Luis C. Garza, photojournalist and curator

What kind of record has your work created?

Gamboa: Because this project began in 1991, I feel like it has captured my own changes in perspective as I’ve grown. Some of the people that are in “Chicano Male Unbonded,” I catch them at a particular point in my career and their career. Many of them are upwardly mobile. Willie Herrón, who I met when we were both 15, and we have gone through like 10,000 different stages, is in there. [Documentary director] Phillip Rodriguez is in there. Chon Noriega [director of the Chicano Studies Research Center at UCLA] is in there. I photographed him when I first met him, but then I re-photographed him when he became director of the center. My son is in there. He was 15 and he is thinking about something that would be actualized — he served 15 years in the military.

There are many people I catch in the moment of aspiring to be. And everyone who is on the wall has made something or done something that has contributed to the fabric of America. On that level, it’s in complete contradiction to the insult that [President] Trump has made upon us.

Garza: That’s the challenge of these exhibitions. Aquí estamos — en frente. [We are here — before you.] That is the statement. That is the stand that we take. And it’s a stand that has a long history. As younger people walk into the exhibition, we are passing the baton for them to carry on.

“La Raza”

When: Through Feb. 10, 2019

“Harry Gamboa Jr.: Chicano Male Unbonded”

When: Through Aug. 5

Where: The Autry Museum of the American West, 4700 Western Heritage Way, Griffith Park, Los Angeles

Info: theautry.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

How 'brown buffalo' Oscar Acosta, best known as Hunter Thompson's Dr. Gonzo, inspired his own TV doc

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.