Column: Art, Reagan and blackface: Edgar Arceneaux examines controversial performance by Ben Vereen

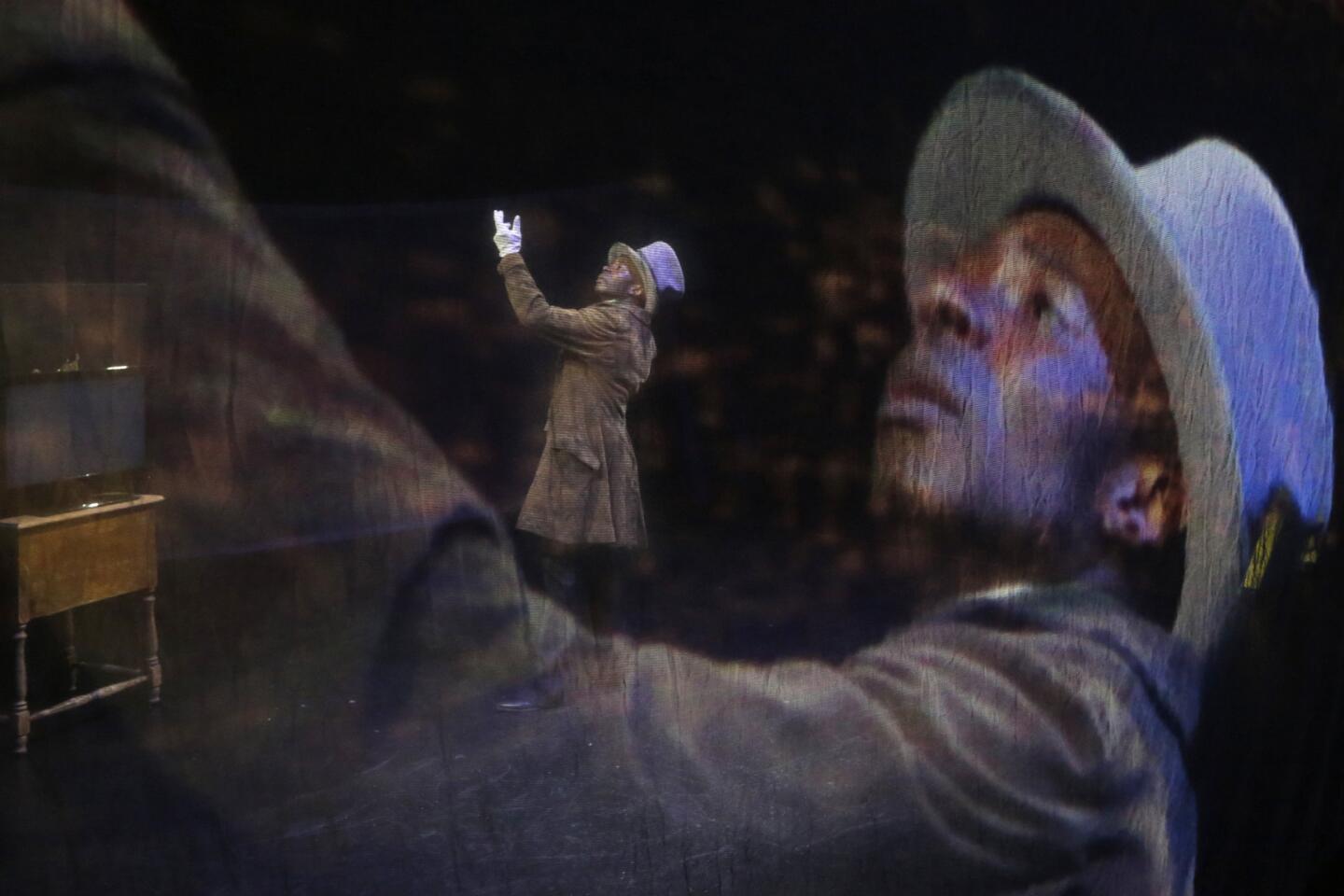

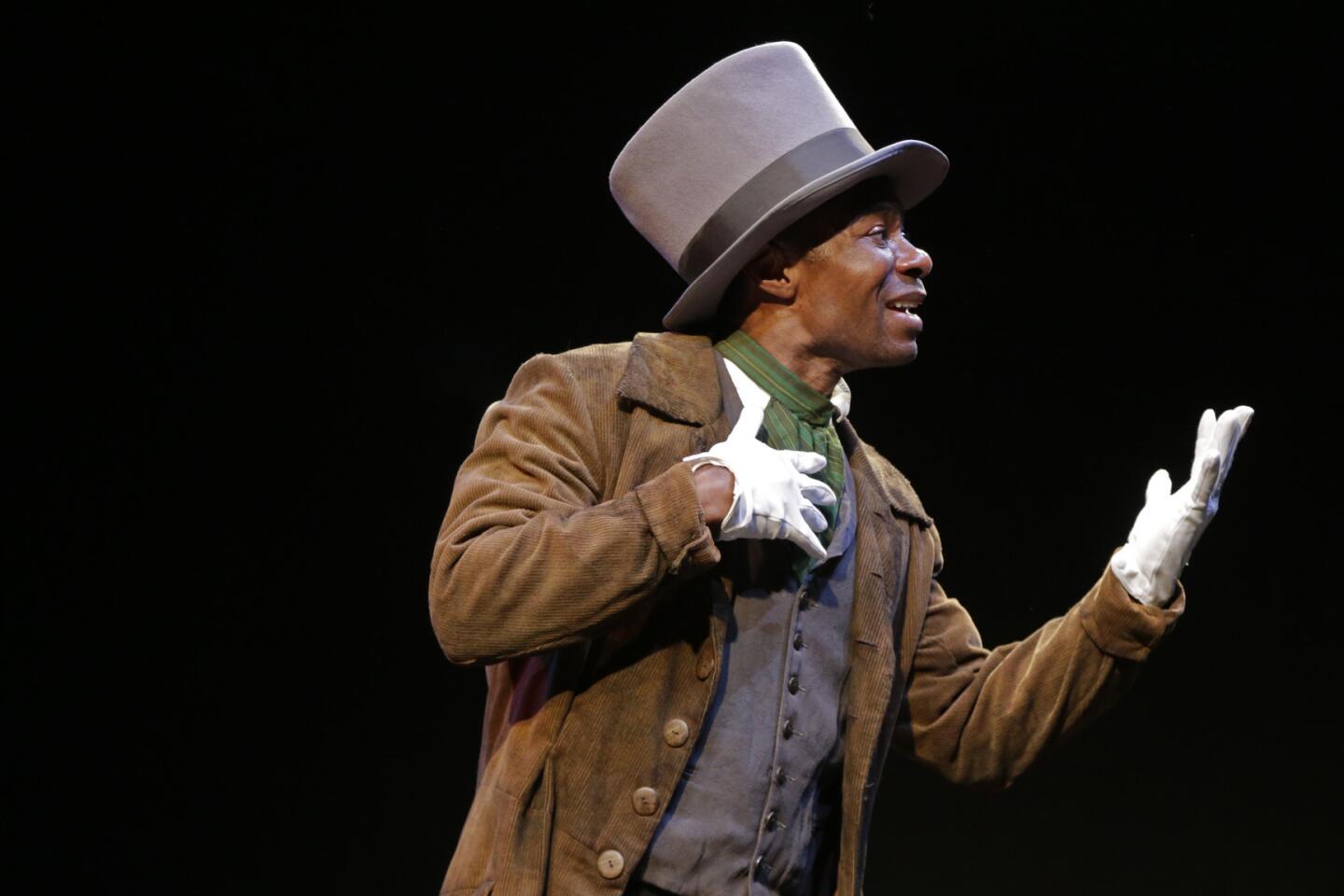

L.A. artist Edgar Arceneaux is revisiting a controversial 1981 performance by entertainer Ben Vereen for a new work to be unveiled at Performa in New York. Above, actor Frank Lawson rehearses a number for the piece at CalArts.

It is late on a Tuesday night, and artist Edgar Arceneaux is standing in the shadows of a black-box rehearsal room somewhere in the labyrinth that is Valencia’s California Institute of the Arts. On one side of the room sits the stage crew, their faces illuminated by the soft glow of laptops and video control monitors. On the other, actor Frank Lawson works out a complicated sequence of steps to a 1912 Dixie show tune.

It is early in the production’s life, and the rehearsal is fitful. Lawson dances. The production team adjusts sound-board levers. The music comes on then goes off. Arceneaux walks steadily around the stage asking questions: “Can I get more volume on this number?” “Can someone please hold this curtain?” “Can I get the red light to hit right here?”

As far as rehearsals go, it is pretty run-of-the-mill — quiet moments of problem-solving punctuated by expressions of “Let’s try that again.” But this production is anything but ordinary. For what Arceneaux is attempting to do is re-create one of the most racially charged performances in recent history.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

“Until, Until, Until...,” as Arceneaux’s experimental play is called, will revisit Ben Vereen’s performance before President-elect Ronald Reagan at the 1981 inaugural gala. Back then, Vereen was a household name — fresh off the success of his appearances in “Pippin” on Broadway and as Chicken George in the TV miniseries “Roots.” For his turn before Reagan, the actor decided to pay tribute to the pioneering African American entertainer Bert Williams — in blackface. Williams had been forced to don blackface on stage during vaudeville productions in the early 20th century. Vereen, in homage, did the same.

For most viewers — who saw the dance via the televised broadcast on ABC — this was a deeply mystifying choice.

“One can only hope it is a masterful put-on,” wrote New York magazine’s Richard West. “Doesn’t [Vereen] know about Republicans?” To others, it was deeply offensive. Actor and playwright Ossie Davis called it “tragic.” Activist Charles E. Cobb stated that he was “insulted, outraged and disgusted.”

“Poor Bert is turning over in his grave,” actress Ruby Dee told Jet magazine at the time.

Arceneaux, left, directs Lawson — who plays Ben Vereen playing vaudeville actor Bert Williams — in “Until, Until, Until...”

Arceneaux didn’t see the performance when it first aired. (He was barely 9.) But he learned about it roughly 20 years ago, while watching a public television documentary about the lives of African American artists.

“I couldn’t understand someone doing a blackface performance in front of Ronald Reagan,” he says. “What ‘Twilight Zone’ of events led to that? He’s alone on stage and all of these Republicans are clapping for him? I’ve been chewing on that performance for years and years.”

Arceneaux’s play, which will debut at Performa, the performance art biennial in New York City, this week, explores some of this dissonance. But more significantly, it looks at the tragedy that can befall a man when television doesn’t tell the whole story.

Vereen’s tribute to Williams had consisted of two parts. In the first, he dressed up in Williams’ stage persona — blackface and all — and performed a rousing rendition of the show tune “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee,” a razzle-dazzle number about a cotton steamer named for a Confederate general.

The song and dance felt jarring — and it was meant to be. For in the second half of the act, Vereen flipped the script. Still in character as one of Williams’ humble stage personas, he offers to buy the wildly clapping Republican audience a drink but is unable to when he is denied service because of the color of his skin. The piece ends mournfully, with Vereen singing Williams’ legendary tune “Nobody” while removing the blackface makeup — a black man whose blackness is accepted only when it is masked by exaggeration on stage.

“It becomes about a person who struggles to hold on to their dignity among this kind of crippling, immense force of shame,” Arceneaux says. “And the way in which [Ben] did it, it was very sincere, very straightforward. It was about the inner struggle of a person who is trying to make something beautiful in a harsh world.”

ABC, however, did not air the second half of Vereen’s act. Instead, as soon as the actor was done with his song-and-dance number, it cut to Donny and Marie Osmond singing a sugar-pop rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “For Once in My Life.” Which meant that anyone following the gala on TV saw only the discordant sight of one of the era’s premiere black entertainers singing and dancing in blackface before the smiling Reagans — and no explanation as to why.

Vereen, reached by telephone in Venice, Fla., where he is directing a new production of the musical “Hair,” says he would have never done the performance at the inaugural if he’d known the entire second half of the piece would be cut from the broadcast. “I was promised the whole thing would be shown,” he says.

He had been willing to go out on a limb with the risky material because he felt it was something that needed to be seen — especially by the incoming Republican Party, which hadn’t historically had a warm relationship with African Americans.

“People say, ‘You did it in front of Reagan,’” Vereen says of his critics. “But he represented so many things that were wrong for us. I felt that if anyone was going to see it, he should see it. But I was sabotaged by the broadcast.”

Arceneaux says the performance and its after-effects are something that he has constantly replayed in his mind. Vereen’s act puzzles him still.

“I can’t quite reconcile it,” he says. “It forces the viewer to say, ‘Is this a good idea or not?’ Yet you can’t put it in one category or another. But that’s what great works of art do. They force you to reorient yourself.

“I was really moved by it. But I was baffled at the same time.”

Lawson says that seeing Vereen’s old performance has been inspiring — despite the controversial material. “Ben is full of charisma,” he says, “one of the best dancers to ever hit the stage.”

The difficult subject of blackface at the Reagan inaugural is not something that Arceneaux, 43, ever thought he’d tackle in his work. Arceneaux is low-key and cerebral, in some ways, the opposite of a performer.

Raised in South Los Angeles, near the intersection of Florence and Western, Arceneaux studied art during the identity-conscious 1990s, first at Art Center in Pasadena, and then at CalArts, where he received his MFA. As a black artist, he says he often felt intense pressure to make work that dealt with his identity. “I was being told to make work about my race,” he recalls. “But I was more interested in epistemology.”

Over the course of his career, Arceneaux — whose art has been shown at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Whitney Museum in New York — has consistently examined points of connection between seemingly disparate things. Through drawings, video and installation and sometimes combinations of all three, he has explored the birth of techno alongside the Detroit riots of 1967 and the work of Stanley Kubrick in conjunction with a policy speech by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“I’m interested in systems and how things related to each other,” he explains, “how certain images become examples of a thing without actually being the thing.”

Artist Edgar Arceneaux during rehearsals for his debut work — which tackles thorny issues of politics, blackface and art.

But something about Vereen’s Bert Williams piece resonated with Arceneaux over the years — even though he’d made a vow to himself that blackface was not the sort of topic he would ever take on in his work. “I felt that there was only one way to talk about it,” he says. “There was no ambiguity about it. It’s a moralized, shameful thing.”

But two years ago, a confluence of events led him to reconsider. He was asked by Performa curator Adrienne Edwards if he’d be interested in creating a performance for the biennial. Then he met Vereen at an event at the Underground Museum, the artist-run exhibition space in Arlington Heights. “It snapped in my head,” he recalls. “I was like, this is the guy who has done the one performance you have never forgotten.”

After some back and forth, Arceneaux was able to finagle a meeting with the actor at his home — where, together, they watched the full tape of the 1981 inaugural performance. “We sit on the floor and he puts it in the DVD player and I’m watching him,” he says. “He’s like, ‘Look at what I used to be able to do. Look at those high kicks.’ I’m sitting behind him watching himself. That’s where the idea for my piece really began to come together.”

“Until, Until, Until...,” which Arceneaux cowrote with artist and filmmaker Kurt Forman, tells the story of the inaugural show from Vereen’s perspective. It travels from the near-present to the frigid days of January 1981, when the young actor is prepping to take the stage at the Capital Centre in his floppy Bert Williams costume.

Like Vereen’s original piece, the play implicates the audience. Seating at the 3-Legged Dog theater in downtown Manhattan, where the play will be shown, will be arranged to resemble an intimate vaudeville club, but part way through, the setting will shift, and the audience will be transported to the square stage and risers of the 1981 inaugural gala. Members of the audience will be invited to occupy the seats that would have been held by GOP stalwarts. So the audience, in essence, will play itself — bearing witness to a performer contending with a complicated legacy: Lawson playing Vereen playing Williams, grappling with the thorny question of race and representation in America.

“The subject matter is absolutely compelling and really quite personal,” says Travis Preston, the artistic director of the CalArts Center for New Performance, an incubator that helps artists produce professional works of theater, including Arceneaux’s play. “The thing that impacts me when I engage it is the awareness of the fragility of the human being before the massive forces of history and media.”

For Arceneaux, it was important that the play not just be about the simple question of blackface, good or bad. “What really interested me in all of this,” he explains, “is how an artist was so gravely misunderstood.”

Edwards, who has worked with Arceneaux throughout the process, says that “Until, Until, Until...,” like the artist’s other work, draws together many disparate points: the history of theater, of African Americans, of the ways in which the Reagan administration represented a pivotal point in the 20th century for the crumbling of New Deal ideals.

“You have the Civil Rights movement and the Black Power movement and right at that moment you have the emergence of Ben Vereen on Broadway,” she says. “All these movements were set to counter and problematize the representation of black people in performance. And we can track it right through Ben Vereen.”

Vereen hasn’t seen the play, but he has confidence that Arceneaux will use his story to create something smart. “I admire Edgar’s art work,” he says. “He’s a man of integrity. And he’s not out to get me.”

But that doesn’t mean that having all of this history dredged up isn’t a little nerve-racking. “There’s always a fear factor,” he says with a sigh. “I felt like a man without a country, a man without friends for a while. Johnny Carson wouldn’t let me on his show. Radio stations would ridicule me.”

Arceneaux says he would have never done the play without Vereen’s blessing. And that if there’s anything the piece might be able to accomplish, it might be the ability to revisit the episode with cool heads and the distance of time.

“I feel like his performance has not been completed,” he says. “I would like the world to see what [Ben] had intended.”

“Until, Until, Until...” will be held at the 3-Legged Dog theater from Nov. 20-22 as part of the Performa biennial. Tickets: $25/30. 80 Greenwich St., New York, 15.performa-arts.org.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.