MOCA-National Gallery of Art deal is an empty prospect

- Share via

A proposed five-year collaboration deal between the troubled Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is, to use a critically astute technical term, a big, fat nothing-burger.

The plan sidesteps the most pressing needs facing MOCA, which are financial health and managerial competence, while needlessly embarrassing both museums.

It’s a symptom of, not a solution to, MOCA’s problems.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture pictures by The Times

A possible relationship between the two — located on opposite coasts and with vastly different missions, structures and reputations — had been talked about in museum circles for weeks. But when the news finally broke Wednesday, the vacuousness of the idea was there for all to see.

The fantasy is that the federal museum will be lending its expertise in exhibitions, research and programming to MOCA. The reality is the reverse. When it comes to the art of the recent past, MOCA is a bona fide star and the Washington institution a bit player. MOCA would be lending its prestige to the National Gallery, not the other way around.

The collaborative idea, which includes zero financial support, apparently means to stick a Good Housekeeping seal of approval on the struggling contemporary museum. Donors are always hesitant to commit to an institution about whose future they are uncertain, which applies to MOCA in the wake of its lingering fiscal woes but not to a federally funded museum.

SPRING ARTS PREVIEW: Art | Theater | Classical

But rather than bolstering confidence in MOCA’s leadership, a foolish plan like this actually lessens it. If MOCA’s leaders are so confused about the relative merits of the two institutions and what is needed to move forward, no wonder its troubles have dragged on for the last five years.

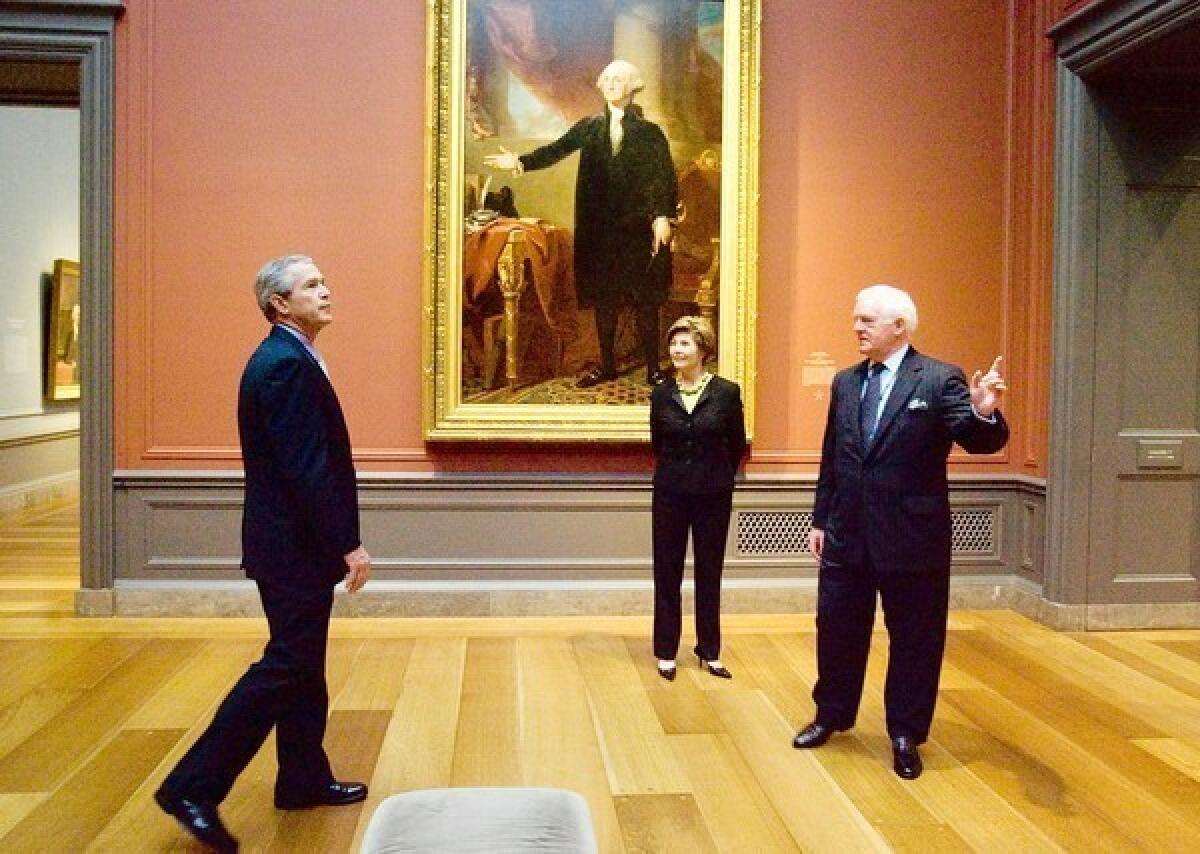

The partnership idea was initiated by MOCA board member Eli Broad, the billionaire collector who is opening his own art museum downtown in 2014, across the street from MOCA. His National Gallery counterpart, board chairman John Wilmerding told The Times, “The hope is that our name, our programming, our expertise gives [MOCA] a sense of backbone and stability.”

Backbone? With all due respect to Wilmerding, it is probably a poor idea to begin a partnership by publicly dissing the other party as effectively spineless. Especially since it’s absurd to imagine that the National Gallery has any useful expertise in contemporary art to offer.

The National Gallery is a wonderful museum — if Old Master European, 19th century American or classic Modern painting and sculpture of the early 20th century are what you want. But the last substantial show of contemporary art I felt compelled to travel there to see was a Willem de Kooning painting survey — in 1994. Art of the last half-century is a minor diversion at the NGA.

Partly that’s because the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden stands right across the National Mall, and international contemporary art is the Hirshhorn’s chief concern. The NGA does next to nothing with recent art, except for photographs and the occasional retrospective of an established, blue-chip American painter or sculptor from the 1950s or 1960s.

Take a look at the museum’s online tour of its Modern and contemporary collection, which features one 1971 sculpture but nothing else from after 1962. Like that De Kooning show, mounted just before the artist’s death, the tour follows the museum’s Old Master profile.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture pictures by The Times

Frankly, I can’t think of a single contemporary thematic or group exhibition of any consequence to have come from there. The National Gallery has a department of Modern art, which begins in the 19th century, but nothing remotely close to a staff specializing in the diversity of global art in our time. Perhaps it’s appropriate for the federal institution to hold back in that area, but it doesn’t mean the museum has any capacity for leadership in a field about which it has virtually no demonstrable expertise.

MOCA, meanwhile, has built an international reputation on a savvy post-1945 exhibition program that uncovers forgotten histories or revises established ones with fresh scholarship and surprising insights. That was a specialty of former chief curator Paul Schimmel, deposed last summer. It’s also the reason two of Europe’s leading contemporary museums — the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and the Ludwig in Cologne — are now directed by former MOCA curators, who left as the institutional problems mounted.

The arrangement with the National Gallery, which might be formally announced next week, is actually rather sad — a throwback to the early 1980s, when MOCA was just a novel idea still being birthed. (Broad was chairman from 1979 to 1984.) The scheme tries to borrow gravitas by association.

Back then, Pontus Hulten was hired away from Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou as inaugural director, and a major chunk of the coveted collection of Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, Europe’s first great collector of contemporary American art, was acquired. Now, America’s National Gallery is signing on as a partner.

SPRING ARTS PREVIEW: Art | Theater | Pop | Country | Jazz | Classical

But who cares? Perhaps to a general audience the partnership looks like a big deal, but to the engaged art public it’s just embarrassing — a desperation move, grasping at straws. In the process, MOCA’s real achievements get misunderstood.

And remember: Hulten soon quit, frustrated with program meddling by MOCA’s board, while Panza went ballistic when moves were made to try to sell off part of his incomparable collection. That MOCA overcame those ‘80s blunders is a testament to its growth — to its own hard-earned artistic gravitas.

In order to begin rebuilding the stature it lost through fiscal mismanagement in the run-up to 2008, MOCA needs just two essential things: smart nonprofit museum leadership at the top, in both the boardroom and the director’s office, and substantial endowment funds — at least triple its $38-million peak a dozen years ago.

A Good Housekeeping Seal from an august but indifferent partner in Washington is just a distraction, unlikely to do anything to fix either gaping deficiency.

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

Depictions of violence in theater and more

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.