Critic’s Notebook: MOCA still mum about curator’s firing, despite crucial questions and too few answers

- Share via

When news leaked last week that the highly regarded chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art had been summarily fired, replaying a similar scenario that had roiled the institution six years earlier, the usual question loomed large: Why?

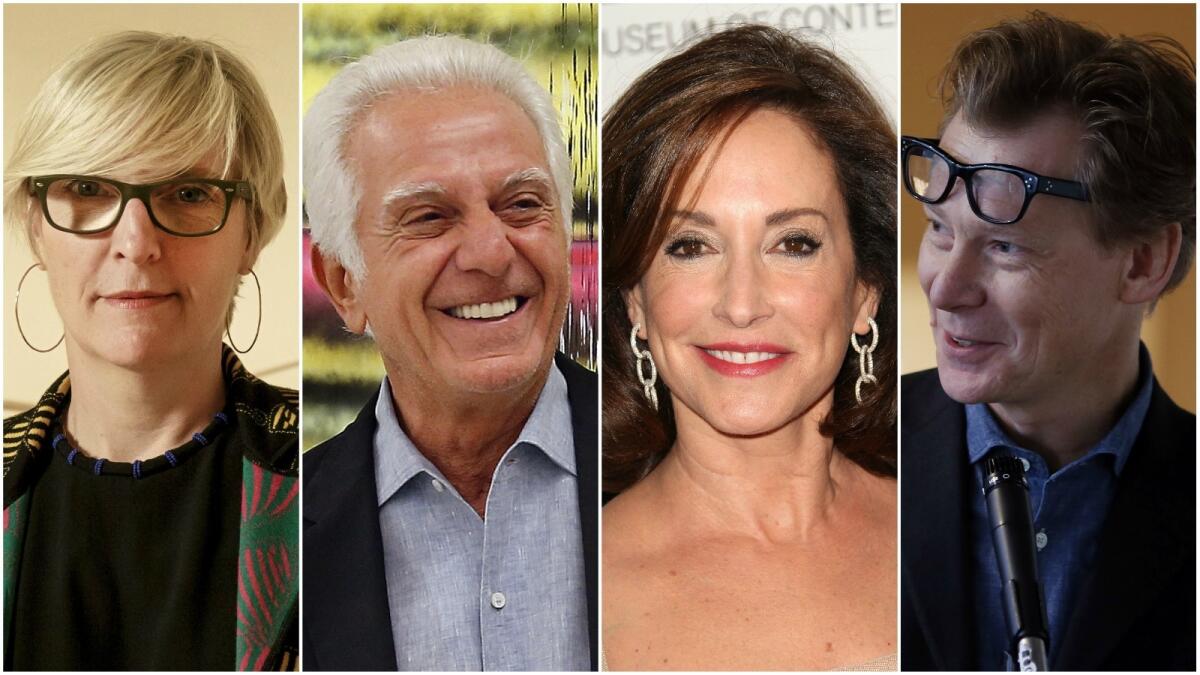

Today, about a week later, we still have no answer as to why MOCA Director Philippe Vergne fired chief curator Helen Molesworth — and we likely won’t. I have a few speculations, which I’ll get to. But the action represents larger stresses vexing the museum world in our New Gilded Age.

A high-profile dismissal such as this one, featuring two widely admired museum professionals, needs to be handled carefully. But it wasn’t.

The abruptness was startling. Tensions were the subject of art-world gossip for months, and the curator had even looked at alternative job possibilities. But when the ax fell, the museum was ill-prepared.

Upon hearing the news, I made my first phone call to MOCA last Tuesday morning around 9:30. It was not answered.

More messages followed. Radio silence greeted them. Nearly five hours passed before a boilerplate official statement arrived, shortly after 2 p.m., citing “creative differences” as the catalyst for a decision “to part ways.”

Total eye-roll. You’d think we were talking about MGM and Judy Garland.

Obviously, the museum had not prepared a graceful exit, nor formulated any plan for informing its public about a decision of profound consequence. As late as Wednesday evening, more than two days after the firing took place, my colleague Deborah Vankin noted that, when asked whether the museum’s board of trustees stood by Vergne’s decision, “MOCA did not respond.” All parties have remained mum.

The administrative failure was glaring. It was also déjà vu: When former chief curator Paul Schimmel was forced out in 2012, the museum took a day and a half to respond.

Once again, MOCA created a powerful information vacuum. Human nature quickly filled it up, shoveling all manner of score-settling accusations, hypotheticals, dark memories of past problems and other dire forms of hand-wringing into the abyss.

Virtually all are overblown — a familiar attribute of life in a digitally connected age. Chaos travels halfway around the social-media world before order puts on its shoes. But MOCA is today what it was last month and last year — a largely stable institution slowly but steadily working its way out of a lengthy period of turmoil. A considerable distance is left to go.

The museum’s board of trustees is not helping nearly as much as it should. One crystal clear sign: The museum is downtown, but board meetings are regularly held 10 miles to the west — at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

On levels both practical and symbolic, the foolish practice betrays a disheartening institutional disconnect at the very top.

The socio-cultural epicenter of L.A. has moved steadily eastward over the last generation, with no signs of a reversal. MOCA could be its crossroads, yet the board of the city’s acclaimed museum devoted to deep engagement with contemporary art and culture clings to the comforts of its powerful westward reaches.

One volatile focus of disagreement, which surely played a prominent role, concerns the planned 2020 retrospective for painter Mark Grotjahn. A gifted artist, the L.A.-born and -based Grotjahn has been working for 20 years. (More than one MOCA trustee is a major collector.) His painterly overhauls of established Modernist propositions can mesmerize.

Grotjahn’s geometric abstractions employ disjointed vanishing points, the kind originally invented to create a convincing figurative illusion but here swallowing up visual energy as if some vividly chromatic black hole. These gave way to monumental faces born of the lozenge-shaped eyes, linear scarification and mask-like bearing in Picasso’s ferocious 1907 Cubist masterpiece, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” Other predecessors as diverse as Paul Klee, Lee Mullican, Jay DeFeo and Mike Kelley ferment in his work. A calculated frenzy dismembers Modernist tribalism.

Grotjahn’s market, although slow to start, has reached stratospheric levels. A 2011 painting sold at auction last year for $16.8 million, reflecting selective new art’s unprecedented role as an asset class like stocks or bonds.

A museum retrospective should unpack art’s critical merits. But another honorable function is to disentangle it from rapacious marketplace hyperventilation, so that it can be clearly seen.

That traditional museum virtue is, however, also a problem — specifically for MOCA. A retrospective for a prominent white male artist with powerful market-winds at his back flies headlong into the programming profile that Molesworth had been laboring toward since arriving at her post in 2014.

The institutional narrative of postwar art is limited, reflecting a general marginalization of women, people of color and artists who lack market success. The constricted story evolved first in New York, a global financial capital, and became nationally enshrined in museum culture. Art historians dismantled the tale over the last 40 years, but museums — already curatorially invested — have been slow to change. They lag far behind.

Molesworth has been clear in numerous interviews that the only way to diversify museum programming is to stop talking about fixing the problem and instead to do it. Pain would inevitably be inflicted.

In 2015, she brilliantly reinstalled MOCA’s permanent collection, rich in Rothko and Rauschenberg, in what I found to be one of the most exciting presentations that year. She explained to an interviewer at Yale University’s radio station how the result both elated and agonized her.

“When you get right down to it, if you’re going to break open the canon, some of the old favorites aren’t going to make it back in right away,” she said. “There’s only so much room. And so five or seven Rauschenbergs did get displaced, so an Emerson Woelffer and a Ruth Asawa could go on the wall. And [that’s] hard for a lot of folks, you know — me included.”

What’s really at issue is museum philosophy and how to open up traditional museum practice.

I was surprised when, just around the time that a splashy New York Times article in July featured museum directors asserting that Grotjahn was due for a full retrospective exhibition — commentary and a publication instrumental in establishment narrative — word began to circulate that MOCA’s director was batting around the idea. The surprise was because the retrospective would suck all of MOCA’s bracing, newly revisionist air from the museum-room.

According to multiple sources familiar with events, Molesworth flatly refused Vergne’s request for a Grotjahn retrospective. For the exhibition program, he was what Rothko and Rauschenberg were for the permanent collection — an absence hard for a lot of folks, me included, but necessary. The more the director appealed, the more the chief curator dug in her heels.

MOCA sent out “save the date” notices for its annual May fundraising gala. It named Grotjahn as honoree. The artist was apparently invited last year by trustee co-chairs Maurice Marciano and Lilly Tartikoff Karatz, although without the full board’s knowledge.

He accepted, later changing his mind. “There is a new urgency to change the power dynamic and we have an opportunity to do so,” Grotjahn wrote to Marciano in a story reported in The Times.

The fundraiser has since been canceled.

Lost in the shuffle were some questions equally as pressing as to why the full board was left in the dark about the choice of a gala honoree.

- Why did the museum confirm a major retrospective for its exhibition calendar when no curator was attached to the project?

- How was the show’s scheduling revealed without an accompanying museum announcement that the artist, one of several on MOCA’s board of trustees, would step down to avoid a blatant conflict of interest?

- When next the board meets at the Beverly Hills Hotel, will its own culpability in the downtown museum’s troubled administrative issues be addressed?

In the firing’s aftermath, the conflict has begun to gel into a simplistic framing that reflects resentments roiling our polarized civic life, with one side characterized as supporting white male artists versus the other’s support for women and people of color. In reality, I’ve no doubt that the director and (former) chief curator both support all of them.

Some evidence comes in the form of Molesworth’s scheduled fall exhibition on American painter and film critic Manny Farber (1917-2008). Farber is a white guy from New York with a major reputation as a sharp movie critic starting in the 1940s and a minor one as a painter of marvelous aerial still lifes and collaged abstractions. His landmark 1962 essay “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” set grandiose self-importance against the power of acidulously burrowing deep into personal passions.

“Masterpiece art, reminiscent of the enameled tobacco humidors and wooden lawn ponies bought at white elephant auctions,” he wrote, eclipses anonymous obsessions “where the spotlight of culture is nowhere in evidence, so that the craftsman can be ornery, wasteful, stubbornly self-involved, doing go-for-broke art and not caring what comes of it.”

Charlie Chaplin versus Buster Keaton, Alfred Hitchcock versus Howard Hawks, Rauschenberg versus Asawa, Rothko versus — well, Manny Farber. It isn’t that the critic did not appreciate Chaplin, Hitchcock, Rauschenberg and Rothko, only that he knew what side he was on in the rolling artistic struggle between dogma and apostasy. The coming Farber show seems to be a history lesson: Molesworth the termite curator working in the white elephant museum, putting some Rauschenberg in storage to make room for a Woelffer and Asawa.

What’s really at issue is museum philosophy and how to open up traditional museum practice. The job is made more difficult than ever as huge buckets of cash slosh around the market — cash often held by museum trustees.

Enormous pressures for a traditional, establishment mechanism for valuing art just rolled over an untraditional, anti-establishment curatorial process that was feeling its way through. The elephant squashed the termite, and it made a mess.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.