Junghwa Hong’s burqa portraits: Can an artist reveal the soul if she can’t see the face?

In her first solo exhibition, Junghwa Hong takes up the burqa, the flowing garment worn by some Muslim women to cover face and body. Her sensitive paintings at CB1 Gallery — the gallery’s last before it closes under contentious circumstances — are a tribute and a question, teasing out some of the thorny issues that swirl around the garment.

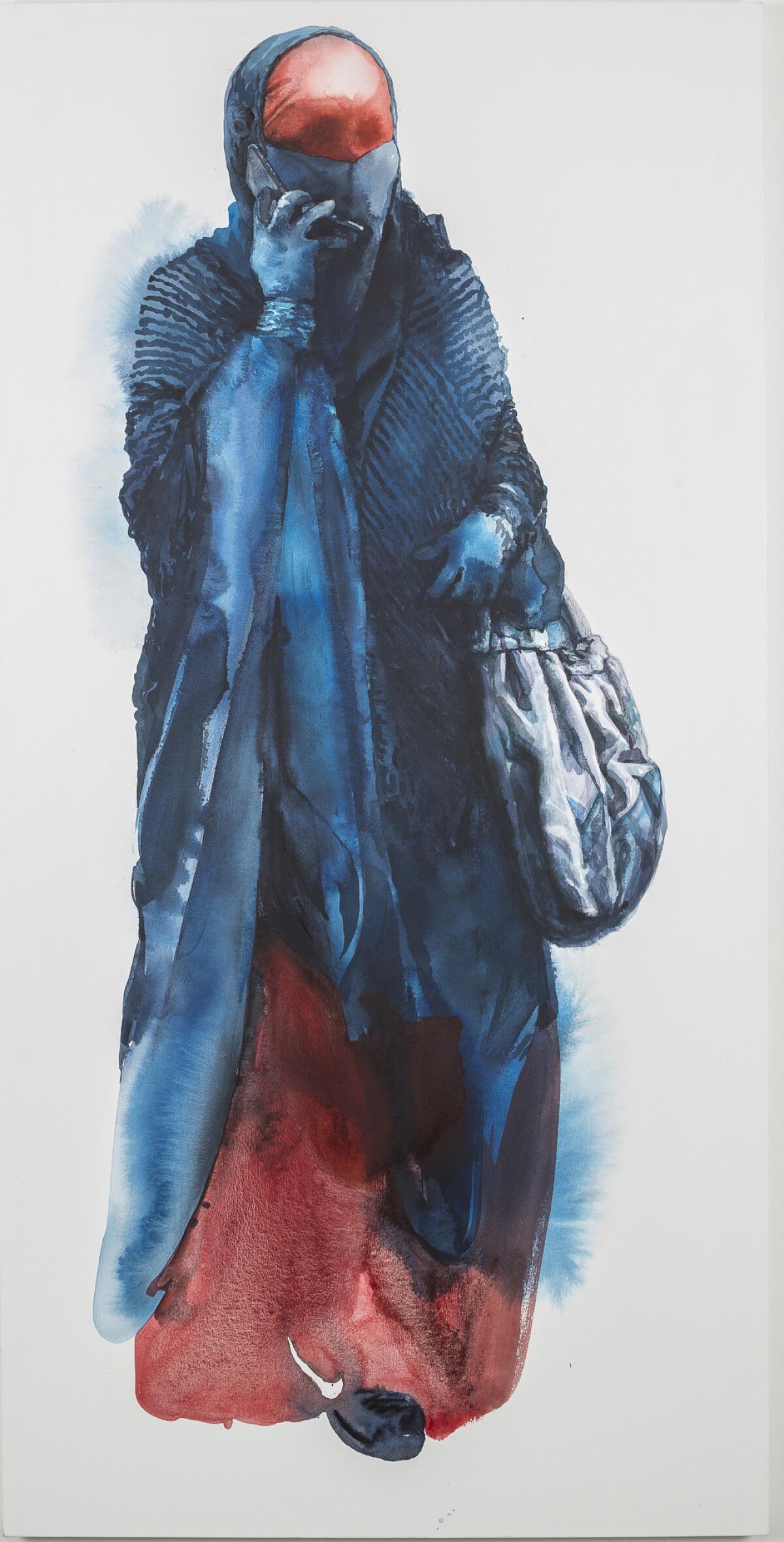

Hong’s portraits are first and foremost humanizing. They depict women wearing the burqa, either in somewhat allegorical compositions or engaged in everyday activities. The figures are derived from photographs Hong found on the internet, isolated on white or blue grounds. They are painted in soft washes of acrylic that bleed like watercolor, with details picked out delicately in graphite. This treatment imparts tenderness and intimacy, and the portraits feel light and translucent, despite the fact that we can’t see anyone’s face.

The symbolic images — a woman holding white doves, another holding a machine gun — are a bit heavy-handed, but the paintings of everyday women fairly crackle with energy. A woman clad all in black with only her eyes showing strides confidently toward the viewer. Another chats on her phone. A gust of wind slightly lifts the hem of a third, revealing sexy high heels beneath her burqa.

In “Picnic,” the largest painting, women clutch lunch bags and drinks; their excitement is palpable although we can’t see their faces. These are images not of shrinking violets but women engaged with the world and one another.

Hong makes a connection between the burqa and the Korean traditions of her own background in the small painting “Jangot.” The titular Joseon-era garment was a kind of hooded overcoat that women wore to obscure their faces from foreign visitors. Interestingly, this painting, created at the same time as the burqa paintings, is executed in relatively stiff, impasto oil paint. It has none of the looseness and light of the other images. Feelings about chauvinism might be more congested closer to home.

Yet, the face of the Korean woman is visible, peeking out beneath her hood, while we see almost nothing of the other women’s faces. The burqa images are an intriguing contradiction: They aren’t portraits in the traditional, Western sense. They don’t reveal the faces and identities of their subjects. They don’t give us access to the eyes as “windows of the soul.” But the sensitivity with which they are rendered makes them portraits nonetheless, raising questions not only about whether we can really “know” these women, but how we define “knowing” in the first place.

CB1 Gallery, 1923 S. Santa Fe Ave., L.A. Closes Saturday. (213) 806-7889, www.cb1gallery.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

ALSO

Miró masterpiece was sold to the highest bidder. It belongs in a museum instead

How Damien Hirst shark art came to swim above the new bar at the Palms in Vegas

From 14 million photos in the Library of Congress, she chose 440 to tell the story of America

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.