Credit where it’s due: Why Gin Wong never quite became one of L.A. architecture’s household names

“I happen to believe in simplicity,” Los Angeles architect Gin Wong once told an interviewer.

In aesthetic terms it’s easy to see what he meant. As a lead designer for William Pereira’s firm and later as the head of his own office, Wong, who died Sept. 1 at 94, often pared down the buildings he worked on to a single memorable gesture.

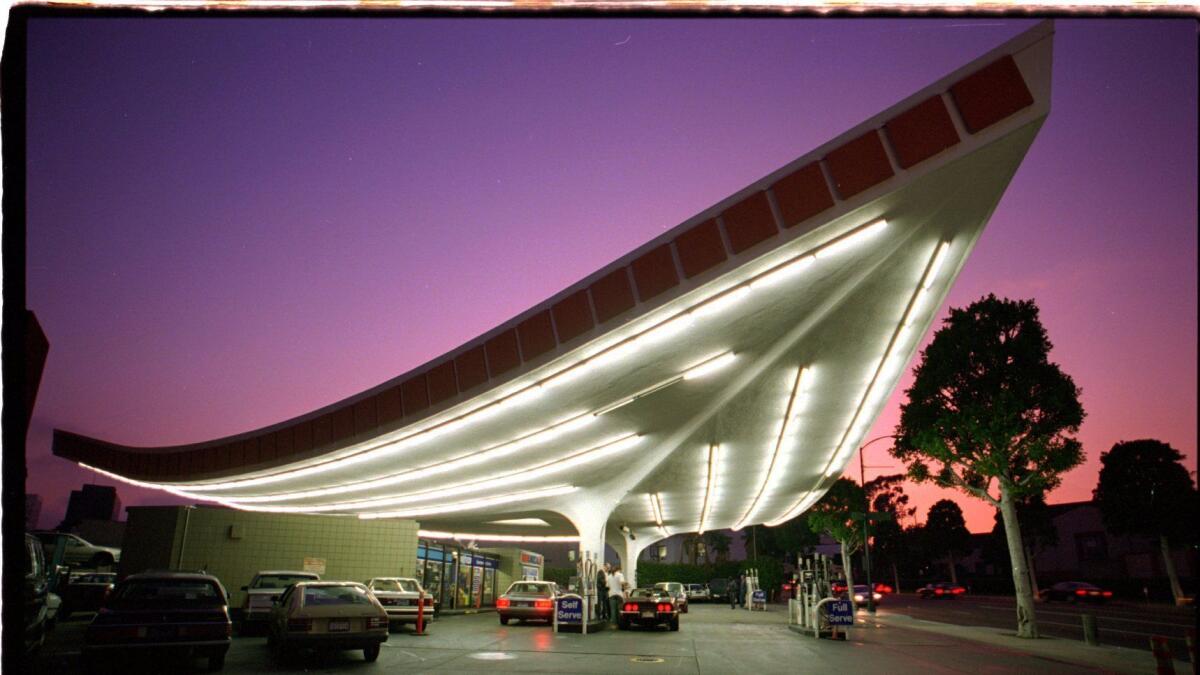

There’s the swooping roofline of the Union 76 gas station in Beverly Hills, among postwar L.A.’s singular landmarks. The peaked silhouette of the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco. The glowing cube at the heart of CBS Television City.

Those forms were memorable in part because they matched the spirit of the age in California. They were a visual shorthand for the future.

The roof of the gas station (originally designed for a site at LAX before being built at the corner of Crescent Drive and Little Santa Monica) is part wing, part wave — perfect for a region boosted by both aerospace and surf culture, by technology and climate. The Transamerica tower rises like a pencil sharpened for the first day of school.

CBS’ “TV City,” as Wong and others called it, was positioned along Beverly Boulevard like a television set newly and proudly installed in an American living room. The complex was built in 1952, just before color TV sets began to be mass produced.

In other ways — in almost every other way — Wong’s career was a study in complexity. Political and ethnic complexity, mostly. And the complicated question of credit in architecture: Who gets it, who doesn’t and who has the authority to hand it out.

Wong was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1922, came to the U.S. as a child and went to high school in the San Fernando Valley. After serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II, he decided to study architecture, first at the University of Illinois and then at USC, where his professors included Pereira.

After graduation, he went to work for Pereira & Luckman and later stuck with his mentor to help run Pereira & Associates, where he became director of design and then the firm’s president. He was a star of those firms. He led the large design team that modernized LAX in the 1950s, readying the airport for the age of jet travel. But it was Pereira, the name partner, who landed on the cover of Time, his confident expression and impressive head of hair under a banner reading “Vistas for the Future.”

When that issue hit newsstands in September 1963, very few Angelenos would have recognized Wong’s name. He was a Chinese American architect in a firm led by a master of architectural marketing and business development. For all the daring of Wong’s work, he was destined to remain one of the associates.

That changed when he founded his own firm a decade later. It was called Gin Wong Associates. Now it was his name on the door, his own flock of associates within. The firm’s projects included another LAX upgrade — this time in advance of the 1984 Summer Olympics — and the 1989 Arco Tower, a sleek skyscraper that helped extend downtown L.A.’s high-rise district west of the Harbor Freeway.

Still, it was I.M. Pei, another son of Guangzhou, who became a media darling in those years — in part because he’d founded his own firm much earlier than Wong, in his 30s instead of his 50s.

“Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945-1980),” a 2012 exhibition at the Chinese American Museum, was part of the first batch of Getty-funded Pacific Standard Time shows. It operated under the reasonable assumption that most viewers would arrive knowing little about the architects it spotlighted, a group that along with Wong included Eugene Kinn Choy, Gilbert Leong and Helen Liu Fong.

“I had no idea that the supervising architect on the design of LAX was Chinese American,” wrote Sharon Mizota, who reviewed the show for The Times, referring to Wong. “This broadening of Los Angeles architectural history is really what the exhibition is about.”

Part of that broadening involves acknowledging the brutal ironies that attached themselves to the work of non-white L.A. architects in the postwar decades. Chinese Americans, like African Americans, were often barred by restrictive covenants from living in the houses they designed.

It also involves upending outdated conventions about who gets credit for designing buildings. The question of authorship is tricky in many creative fields, including — famously — filmmaking. But our understanding of how movies are made has at least evolved over the years, thanks in significant part to the battles over auteur theory that consumed Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael and other film critics in the 1960s and ’70s.

In architecture, that conversation has remained stunted. Who designed the Capitol Records building in Hollywood, Welton Becket or Louis Naidorf? Just how much was the architecture of L.A. firm Morphosis affected when co-founder Michael Rotondi departed in 1991, leaving Thom Mayne without the humanizing balance his partner tended to provide? Did Renzo Piano’s designs lose some elegance when the brilliant structural engineer Peter Rice, a longtime collaborator, died in 1992? Did Frank Gehry’s work change appreciably when Edwin Chan left Gehry’s office in 2011?

I’ve tried to bring these questions into the open over the years. So have other critics. But for the most part they remain the stuff of cocktail-party chatter and architectural gossip. There are headline writers and readers (and architects and critics as well, to be perfectly honest) who prefer the tidier narrative offered by a “Norman Foster building” or “Zaha Hadid icon.”

If not for the persistence of that narrative, Gin Wong’s contribution to postwar L.A. would be far better understood. It’s that simple.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.