Review: What to see in L.A. galleries: tiny paintings of breathtaking beauty, photographs of the super-smart

- Share via

At a time when those who shout loudest seem to get more attention than those who speak softly, it’s refreshing to come across Yui Yaegashi’s whisper of an exhibition at Parrasch Heijnen Gallery.

Titled “Fixed Point Observation,” the Tokyo-based painter’s first solo show in Los Angeles fills the large rectangular space with the kind of silence that lets you know something important is taking place.

The soundless stillness that spills from Yaegashi’s intimate abstractions has nothing to do with the silent authority of solemn situations or sacred spaces. It has, on the contrary, everything to do with those fleeting moments when you see something beautiful and your breath catches — not so long that you get lightheaded, but just long enough to notice that you are in the presence of something special.

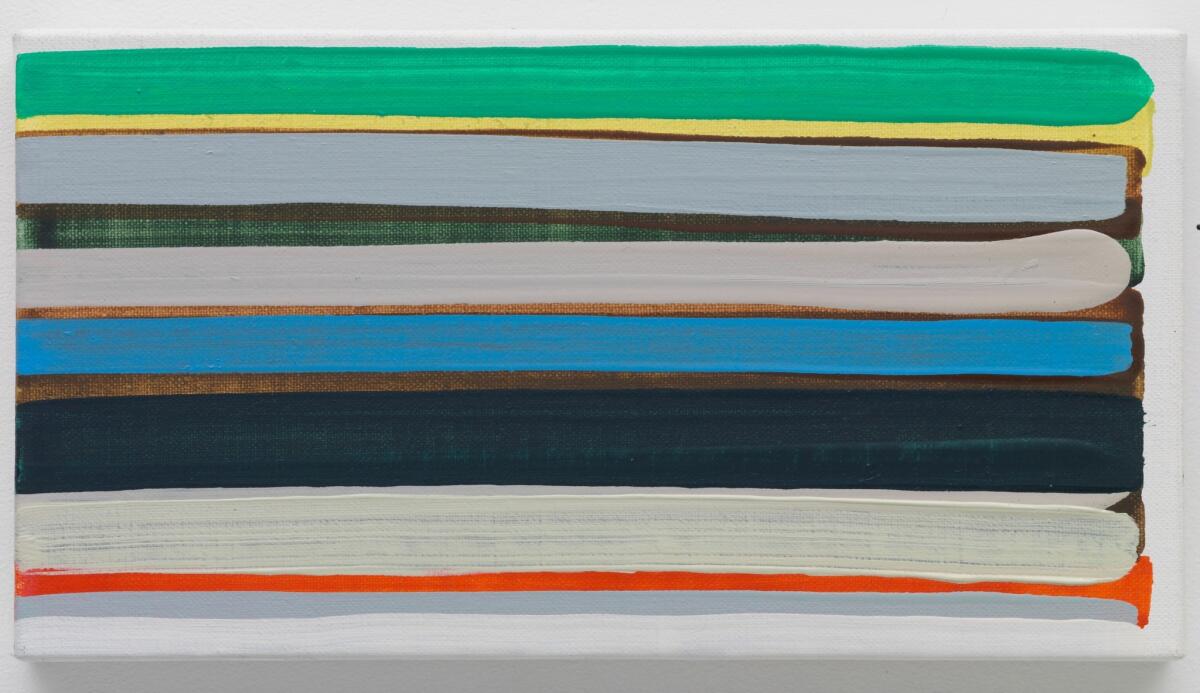

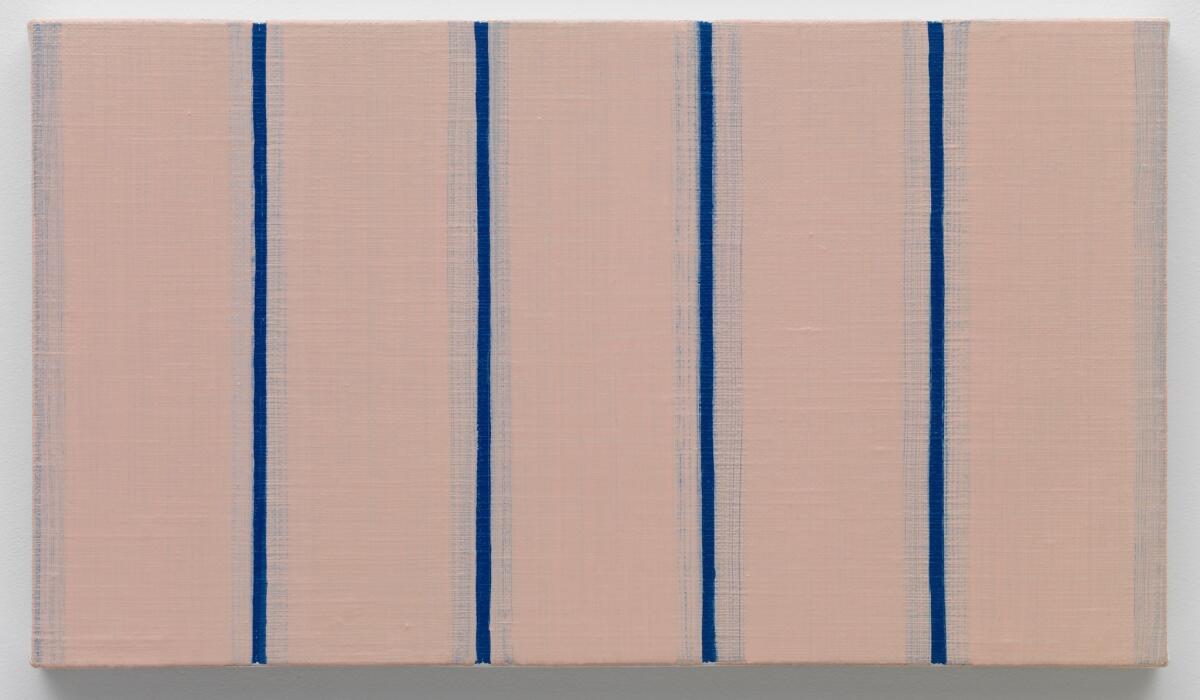

Part of the pleasure is that it is unexpected. The elusive beauty embodied by Yaegashi’s paintings comes in canvases that are tiny, as small as 7¼ inches by 5 inches. Installed with a lot of bare wall between them, her 12 abstractions make the gallery seem cavernous.

You have to stand very close to each painting to see its subtle shifts in texture, color, luminosity, translucence and depth. Every brushstroke matters.

Sometimes Yaegashi uses only one color. But the direction she has dragged her paintbrush has created a surface that appears to be woven, its overlapping elements forming a complex pattern so granular that it seems to be made up of microclimates.

At other times, she paints over previous compositions, leaving only slivers of what once existed. At still others, she establishes patterns that change as your eye glides across them, creating gentle visual turbulence. So refined is Yaegashi’s paint-handling that the marks made by the individual bristles of her brush matter in ways rarely seen.

Casually elegant — and unselfconsciously gorgeous — her understated paintings strike just the right balance between restraint and abandon. Even better, they draw viewers into the action, their modest dimensions pulling the rug out from under the idea that bigger is better and loudest is best.

Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, 1326 S. Boyle Ave., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 21; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 943-9373, www.parrasch-heijnen.com

Over the last decade or so, modern technology has made it possible to crunch big numbers. Scholars and scientists have been using computers to analyze massive volumes of data. Market researchers have been doing something similar, charting the buying habits of consumers.

Now artists are in on the action. It’s not a pretty picture.

At the El Segundo Museum of Art, “Brain: Photographs by Peter Badge” presents two rows of black-and-white photographs lining the four walls. There are 396 photographs, each a head-shot of a Nobel laureate. All have been numbered, from 1 to 396.

To find out more you must turn to one of the touch-screen monitors that have been mounted at various intervals along the walls. There, you can scroll through a grid of numbers, tapping any one to discover some basic information about the person in the picture. (You also can do that online, by going to www.esmoa.org and clicking on “Experience 25: Brain,” then clicking on “Brain Grid.” Details of the photographs in the exhibition are reproduced digitally, along with snippets about each laureate.)

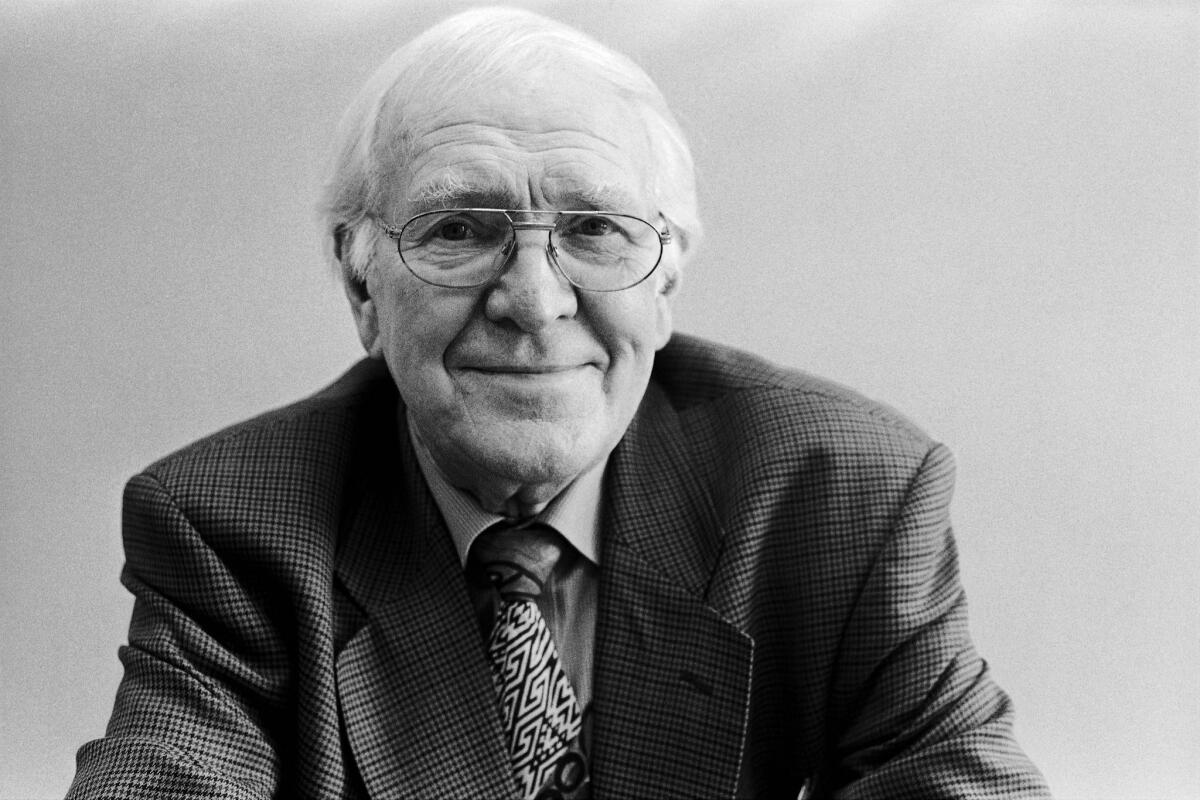

No. 32 identifies the smiling man in the photograph as James W. Black from the United Kingdom. He was awarded the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine in 1988, along with Gertrude B. Elion and George H. Hitchings, “for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment.”

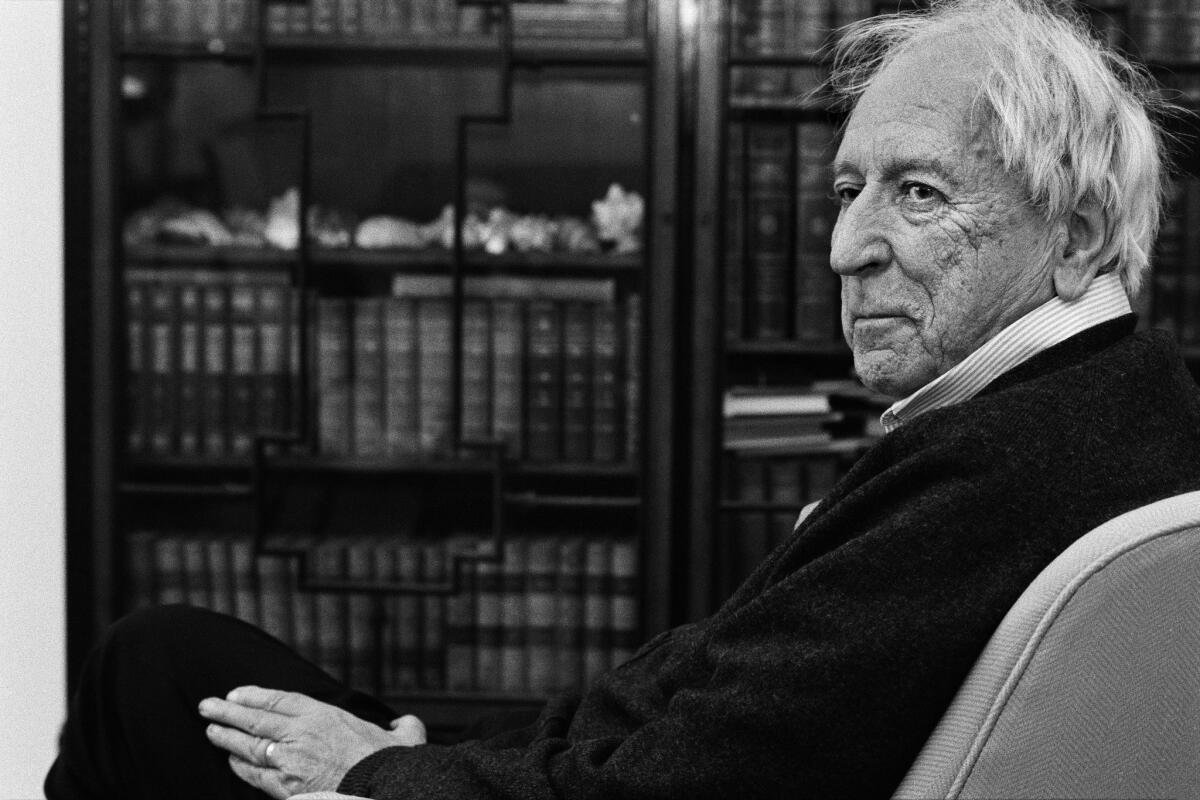

No. 358 is Tomas Tranströmer, from Sweden, who won the prize for literature in 2011, “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he give us fresh access to reality.”

That’s what’s missing from the exhibition. It’s a big data dump that leaves visitors lost in details that Badge didn’t bother to organize or analyze or interpret. That is the very stuff of art, not to mention science and scholarship and knowledge building.

I imagine that Badge wanted to leave visitors free to come up with their own interpretations and analyses of his works. But his photographs are too anodyne to take us past the obvious. Most are no more captivating than the generic headshots and snapshots that can be found online.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

He has been working on this series since 2000, photographing prize-winners from 1954 to 2015 in chemistry, economics, literature, peace, physics and physiology or medicine. They come from all over the globe.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to see that most of the photographs depict old white men. If I had a research assistant, I’d have him count and graph the age, ethnicity, gender and nationality — among other characteristics — of the laureates.

But that information would need lots of interpretive work to produce anything more than anecdotal curiosities. Unfortunately, “Brain: Photographs by Peter Badge” doesn’t go that far.

El Segundo Museum of Art, 208 Main St. Open Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, through Feb. 12 (check for holiday closures). (424) 277-1020, www.esmoa.org

Four whimsical sculptures by Hannah Greely and six haunting drawings by the late Avigdor Arikha make for a moving exhibition at

On the surface, the two artists’ works have little in common.

Using cardboard, plaster, papier-mâché and tempera paints, Greely, 37, builds flimsy vignettes that seem to spring from a grade-schooler’s imagination. Cats, geese and trees (both pine and palm) star in her dreamy scenarios, which are set in a pup tent, on a spiral staircase and in a gravity-defying still life.

Arikha (1929-2010) used pencils, pastels and watercolors to render, on small sheets of paper, things that made up his immediate environment: a red necktie, a partially peeled apple and a bowl of black olives, as well as a pair of mismatched gloves, a trio of gift boxes and the view from the window of his New York apartment. His touch, neither rough nor delicate, still cuts through distractions to get to the raw essence of stuff.

To see Greely’s handcrafted tableaux and Arikha’s astutely observed images in juxtaposition is to understand that both were made to take visitors beyond appearances, into a world of unexpected discoveries, stirring insights and deep affinities.

Greely’s handcrafted tableaux do so by bringing the logic of dreams front and center. Arikha’s intimate pictures do so by capturing the fugitive beauty of simple things, their impact all the more poignant for being impossible to hang onto.

Paired, the artist’s works are more potent. Next to Greely’s 3-D images, Arikha’s pictures are less melancholic than they might be on their own. Similarly, the juxtaposition gives Greely’s lighthearted pieces greater depth and resonance.

With little drama and less fanfare, the untitled exhibition puts visitors in touch with a world that can be sensed but not seen, evoked but not exposed.

Michael Benevento, 3712 Beverly Blvd., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 14; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 874-6400, www.beneventolosangeles.com

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Artist Alberto Lescay didn't just create Cuba's largest sculpture, he's teaching a new generation

Luchita Hurtado abstract artworks mix cultures like colors, to rousing effect

Harry Gamboa Jr. stages a fotonovela at the site of L.A.'s demolished 6th Street Bridge

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.