From ‘Tintin’ to ‘Zootopia’: A peek inside two Paris exhibitions celebrating a century of animation

The French may hold animation, graphic novels, comic books and comic strips in higher regard than Americans do, if the crowds at two museum exhibitions here are any indication.

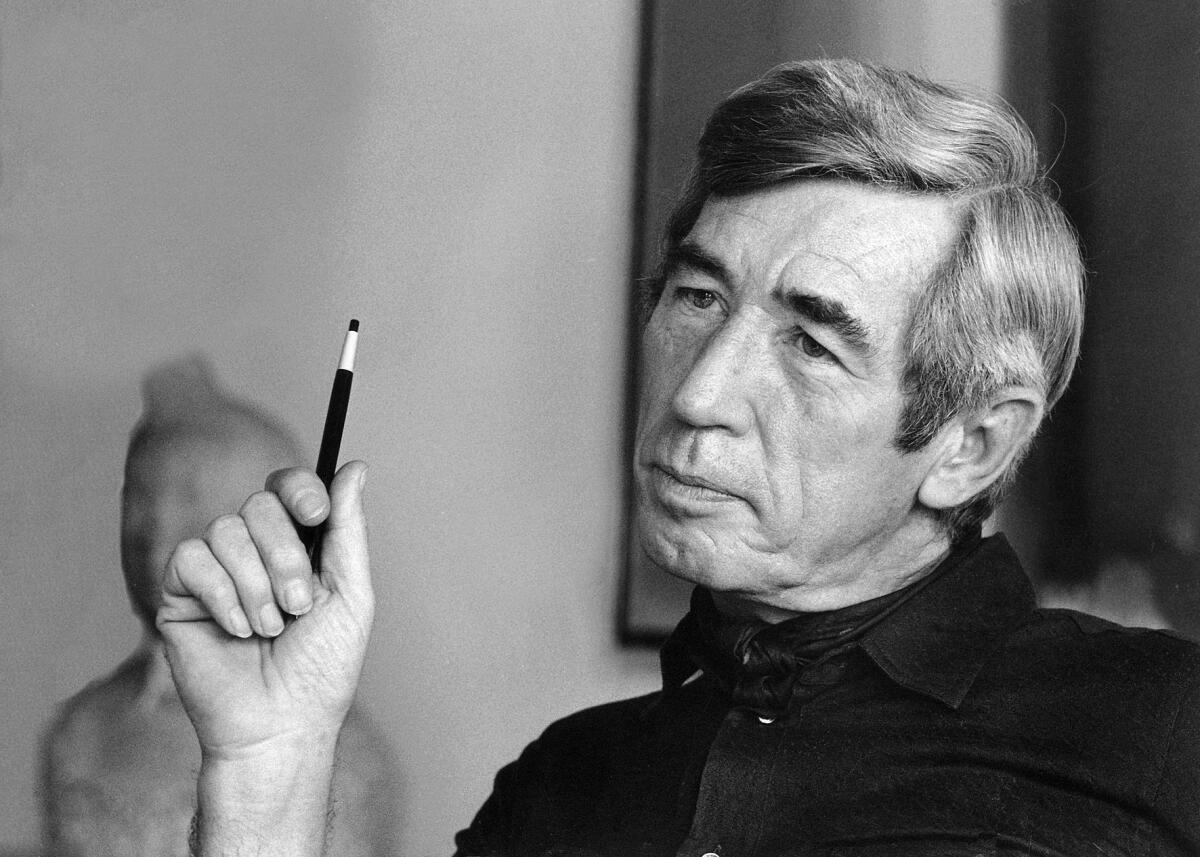

“Hergé,” a survey of work by “Tintin” creator Georges “Hergé” Remi, is running at the venerable Grand Palais through Jan. 15; across the Seine, Art Ludique-Le Musée is offering “The Art of Walt Disney Animation Studios: Movement by Nature” through March 5.

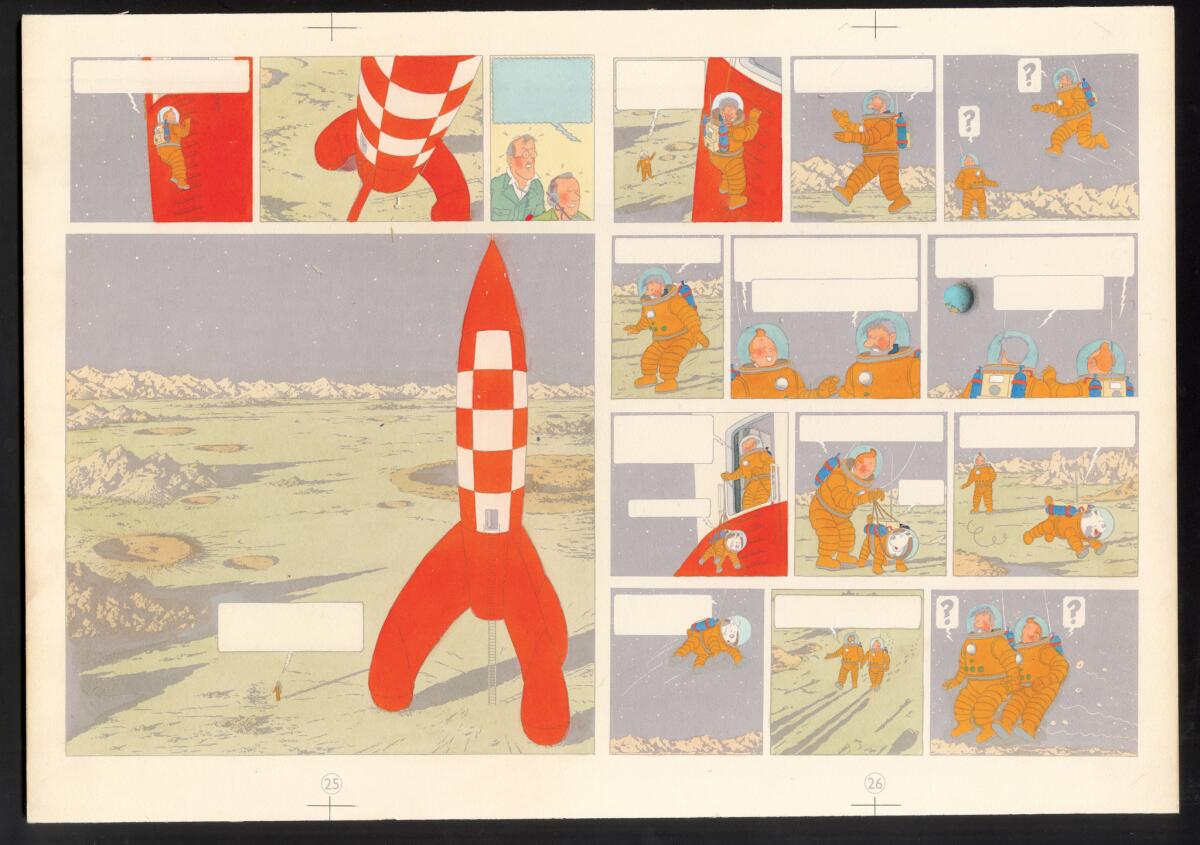

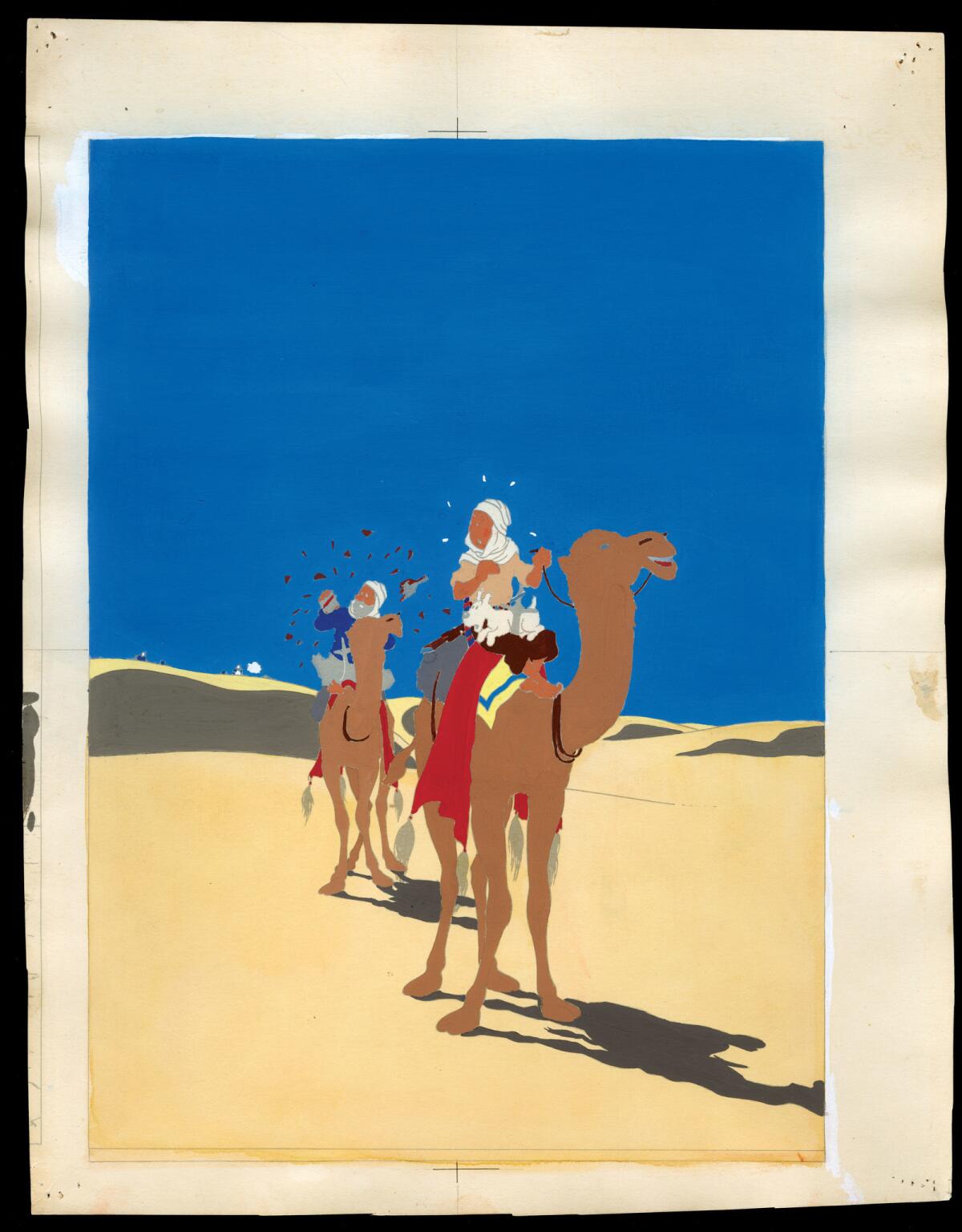

In 1929 Belgian cartoonist Hergé scored a hit with a comic strip about an intrepid boy reporter, Tintin, and his fox terrier, Milou (Snowy in English). It appeared in the children’s newspaper supplement le Petit Vigntième (the Little 20th). Since then, more than 200 million Tintin books have been sold in 70 languages, and Hergé's work has influenced generations of cartoonists, as well as pop artists Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. This extensive exhibit includes some of Hergé’s previous strips, his Art Deco advertising work and some early paintings.

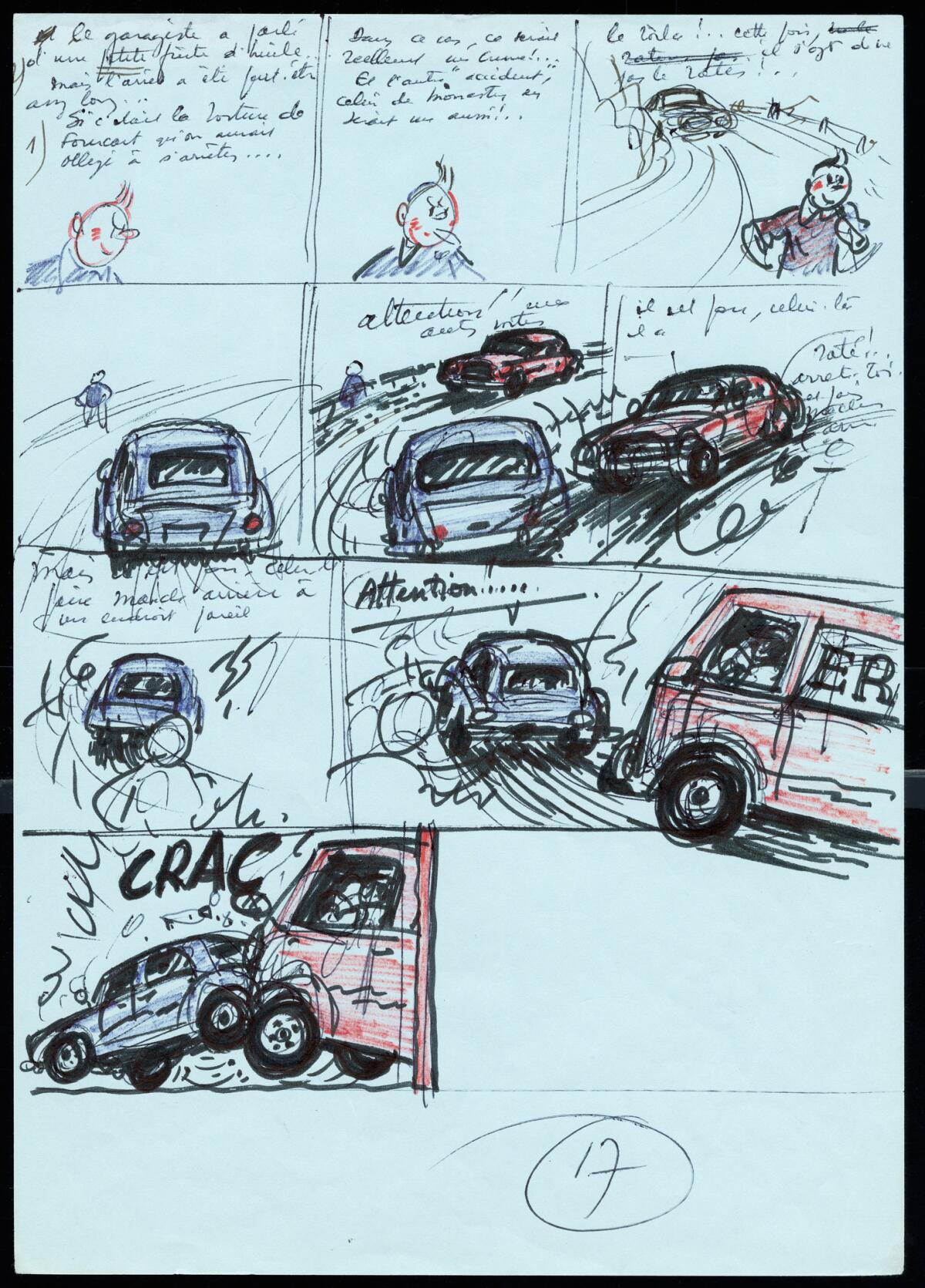

The most interesting pieces in the show are the rough pencil drawings of “Tintin,” which show the artist looking for the shapes that will make the characters and settings read on the printed page. Hergé's direct, immediately recognizable style was based on what he called "the clear line," but his roughs are masses of scribbles, erasures and re-drawn forms that reveal his mind at work.

Unfortunately, the exhibit is poorly laid out. It’s often hard to tell which room should follow which, and examples of work by artists Hergé cited as influences feel out of place at the end of the show. They belong at the beginning. But nearly 90 years after he went to the Soviet Union on his first assignment, Tintin shows no signs of waning popularity, and the crowds are lining up outside the Grand Palais.

The “Movement by Nature” exhibition at Art Ludique, although smaller than the comprehensive “Once Upon a Time, Walt Disney” show held at the Grand Palais in 2006, is a well-curated and well-presented delight.

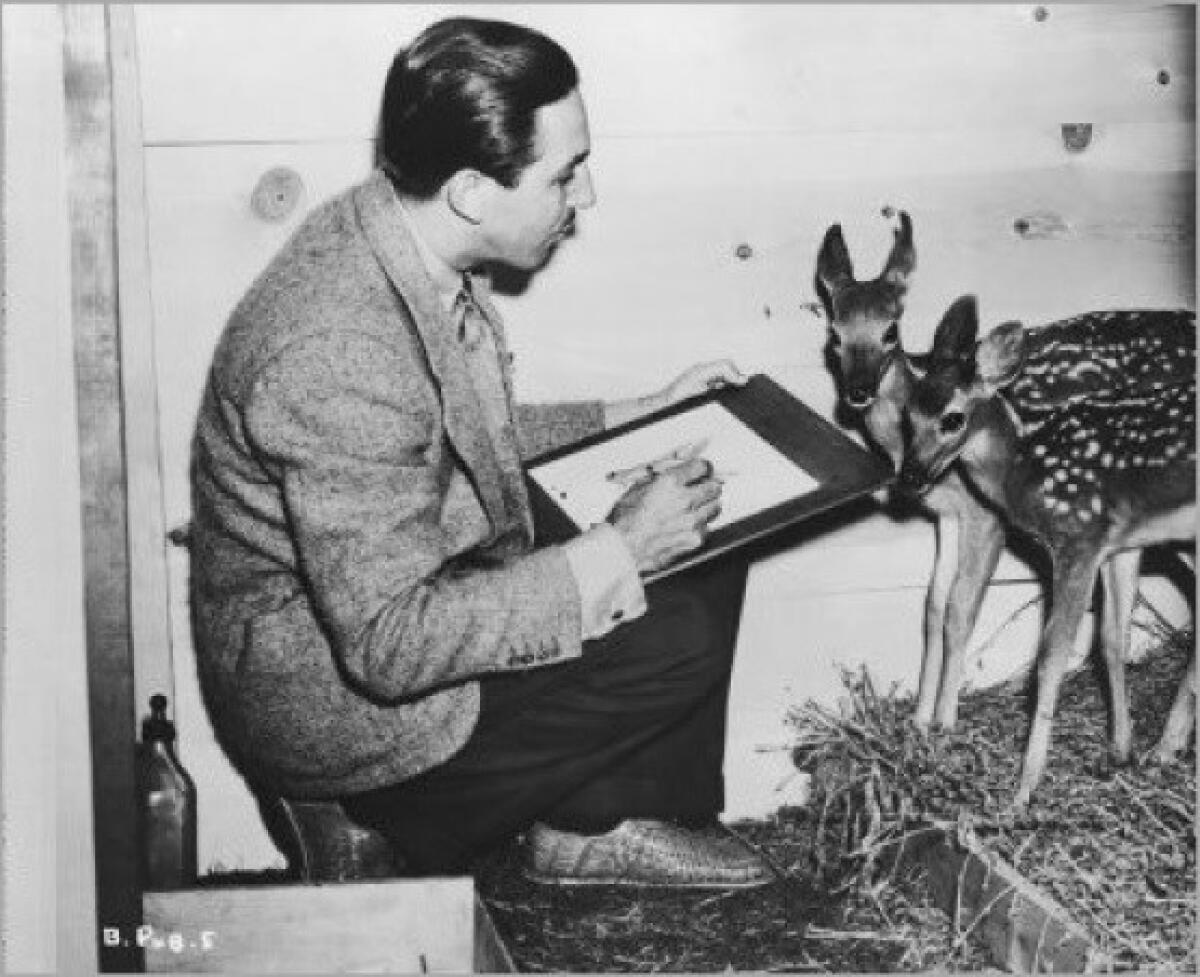

Working with the Disney’s Animation Research Library, museum President Jean-Jacques Launier and his staff have chosen materials that emphasize the technical and artistic innovations Disney introduced, and the links between the classic Disney films and the studio’s recent string of CG blockbusters. The younger artists have clearly studied the work of their illustrious predecessors and learned from them.

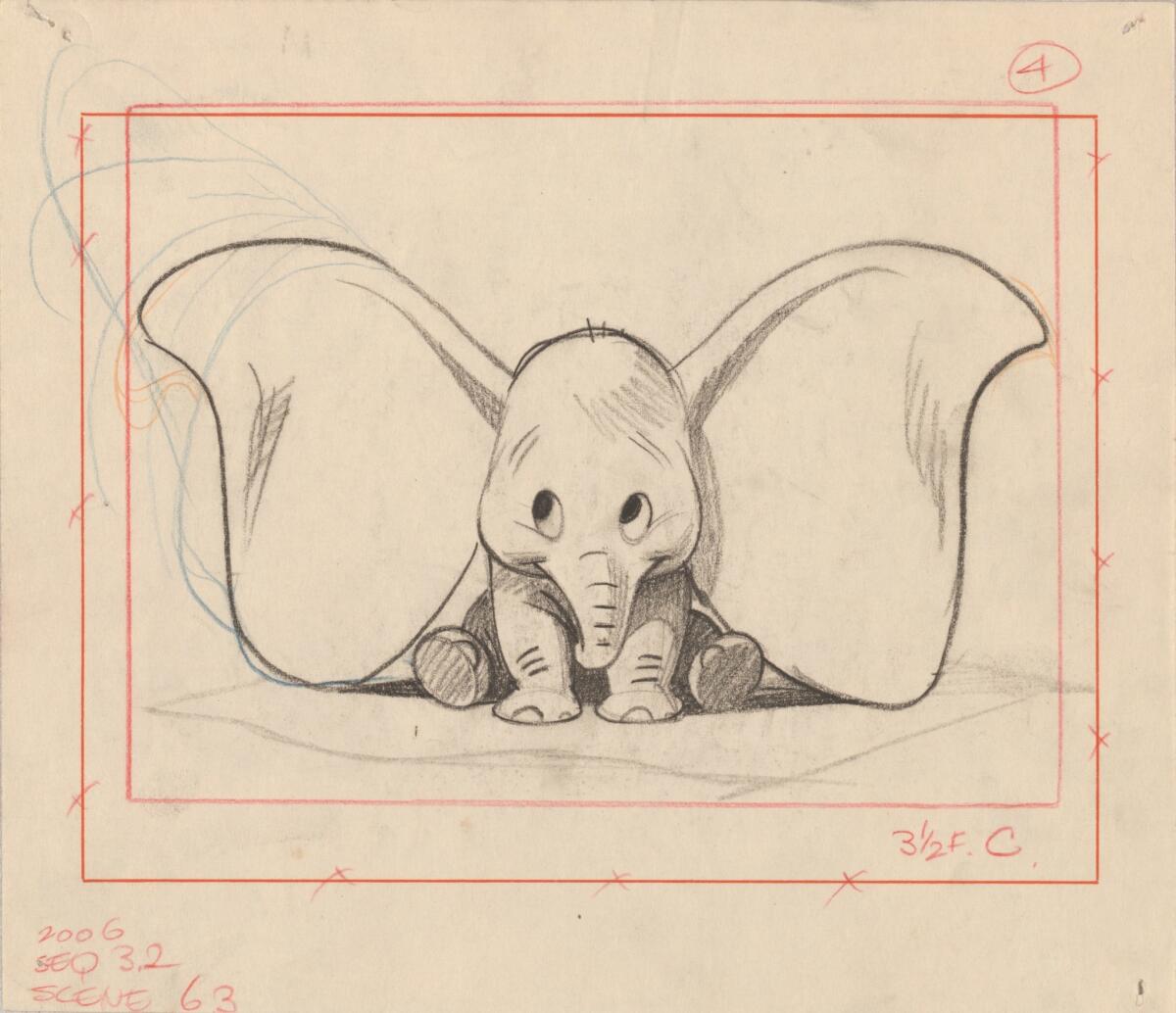

Joe Grant’s preliminary sketches of the Queen from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” deftly capture her icy vanity; Jin Kim’s studies of the lead characters in “Frozen” and “Big Hero 6” suggest a comparable level of vitality and psychological insight. Atmospheric studies by Paul Felix for “Tarzan” and Ryan Lang for “Big Hero” reflect the influence of Tyrus Wong’s exquisite watercolors that set the look of “Bambi.” Byron Howard’s digital rendering for “Zootopia” of disgruntled fox Nick Wild in a commuter car full of rabbits telegraphs exactly what he’s thinking — as do a series of studies of Pinocchio and Geppetto done in colored pencil decades earlier.

Animation drawings from “Pinocchio,” “Fantasia,” “Alice in Wonderland” and “101 Dalmatians” by Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, Ward Kimball, Woolie Reitherman and Frank Thomas — six of Disney’s celebrated “Nine Old Men” — set the standard for fine draftsmanship and consummate acting. More recent work for “The Little Mermaid,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Lion King” by Ruben Aquino, James Baxter, Andreas Deja and Glen Keane showcase the influence of the older masters and the new artists’ individual talents.

“Movement by Nature” includes some rarely seen treasures. A page from the scenario for the groundbreaking “Steamboat Willie” and the accompanying animation drawing by Ub Iwerks mark the birth of Mickey Mouse, still the world’s most famous animated character. A series of watercolors by Mary Blair for “Saludos Amigos” reveals her transition from the more realistic style of the California School to the brilliant palette and simplified forms that mark her work for “Alice” and other features. The “Alice” studies, which pack so much color and life into a few square inches, show why Blair ranks as one of the most admired designers in the history of animation.

Art Ludique-Le Musée is across the Seine from the Cinémathèque Française, which boasts an unmatched collection of early animation devices that complements the Disney exhibition. Together, they offer visitors to Paris rare insights into the art form. It will probably be a long time before major American museums devote comparable space to Carl Barks, the Hernandez brothers, Studio Ghibli or Aardman Animations.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.