Review: ‘Carleton Watkins: Making the West American’ sheds light on the photographer who artfully captured early California

- Share via

How does a biographer tell the story of a person’s life when the textual sources usually marshaled to help map it have almost all disappeared?

Birth, marriage, death and other official certificates missing. Business records of occupations held, deals consummated, momentous transactions attempted or failed — mostly gone. Personal correspondence with loved ones, mere acquaintances and assorted strangers, as well as diaries and notebooks, largely vanished.

What if the paper trail has been pretty much shredded?

This was the unnerving prospect faced by Tyler Green, a former journalist and host of the popular podcast “Modern Art Notes,” when he embarked on research more than six years ago to write “Carleton Watkins: Making the West American.” I’ve followed his progress, both on social media and in conversation, given my own intense admiration for the artist’s work — and I was gobsmacked by a revelation that comes 21 chapters in (more about that in a moment). The fascinating and indispensable book is finally being published in October by the University of California Press.

The last quarter-century has seen Watkins emerge, if not exactly from obscurity — in his lifetime, he won prizes from Europe to Australia — then certainly from the shadows, as an essential figure of 19th century American art. A photographer, his brilliant landscape compositions rank in significance with those painted in oil on canvas by such major contemporaries as John Frederick Kensett, George Inness, Frederic Edwin Church, the British-born Thomas Cole and the Prussian-born Albert Bierstadt. The lack of a Watkins biography was a gaping hole in our historical understanding of American art.

Lost images

California’s art history is distinctive because it begins not with a painter or sculptor but with a photographer. Watkins seized a new medium, barely a decade old when he was born, and invented a fresh pictorial language. His remarkable life, buried and obscured, has been a missing link.

Cruel fate had intervened.

Watkins was 86, blind and destitute, when he died at the Napa State Hospital in June 1916. He lived far longer than the great East Coast painters with whom his unprecedented Western landscape photographs favorably compare. (Cole was barely 47 when he died, while Church — the eldest — was nearly 74.) But Watkins had suffered a cataclysmic event, a shattering episode both personally and professionally, with which Green opens and closes his book.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake rippled through the city on April 18, its terrifying Richter scale magnitude estimated as high as 7.9. Over 45 long seconds, buildings toppled, water mains were severed and gas lines ruptured. What the fearsome shaking and its relentless aftershocks didn’t destroy, the raging fires mostly did.

Watkins’ legacy was almost destroyed too. An unidentified photographer’s extraordinary picture, housed today in UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, shows Watkins as a frail, shadowy figure leaning on a cane, steadied by two younger men, as he makes his way gingerly along a rubble-strewn sidewalk. Flames burn in buildings across the street, a storm cloud of gray smoke rising behind him. One man carries a simple box tied with rope, perhaps his sole intact possession.

Watkins’ apartment was wrecked. In a brutal twist, he had been assembling his life’s work for transfer to nearby Stanford University. Disaster struck just days before the voluminous material was scheduled for the move. Hundreds of glass plate negatives broke, an untold number of images printed on paper burned, carefully maintained documentation went up in flames.

History was unmade.

Stanford already had a collection of Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering photographic studies of animal locomotion, which eventually contributed to the development of motion pictures. But Green notes that they had been obtained with a cache of family possessions of Leland and Jane Stanford, the university’s founders. The Watkins collection apparently would have been the first American museum acquisition of photographs as art, complete with the artist’s archive.

The unprecedented institutional recognition of a photographer as a major figure in post-Civil War America, Green writes, would likely have played “a pioneering role in elevating both Watkins as an artist and photography as an important art historical discipline nearly a hundred years earlier than it did.” Given Watkins’ splendid photographs, especially from the 1860s and 1870s, it is hard to disagree.

The book’s central argument, convincingly made, is that Carleton Watkins and his photographs are central to the story of 19th century American art. The artist has long been recognized as instrumental in Abraham Lincoln’s landmark 1864 decision to create the nation’s first federal parkland, saving for posterity the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, thanks to Watkins’ stunning landscape photographs of the region.

True — but that’s not the half of it.

Green expands on those photographs’ deeper meanings. Just as the photographer loaded his mule cart and ventured into the rugged Yosemite wilderness with 2,000 pounds of survival provisions and bulky equipment — an enormous bellows camera he built from scratch, glass plates for negatives, volatile chemicals for fixing images and more — the very fabric of the national ideal was being torn asunder by a brutal civil war. The art Watkins made firmly resisted the war’s anguished split.

Cultural unionism

The book follows two primary paths. The first is familiar, the second novel and uncharted.

First, landscape was the great subject of mid-19th century American art, as evidenced by the celebrated paintings of idealized natural beauty by the Hudson River School. Second, from 1861 Watkins’ work invoked that young but dominant new painting tradition, birthed only in the 1830s. His pictures gave distinctive shape to the vague and unstructured idea of the American West.

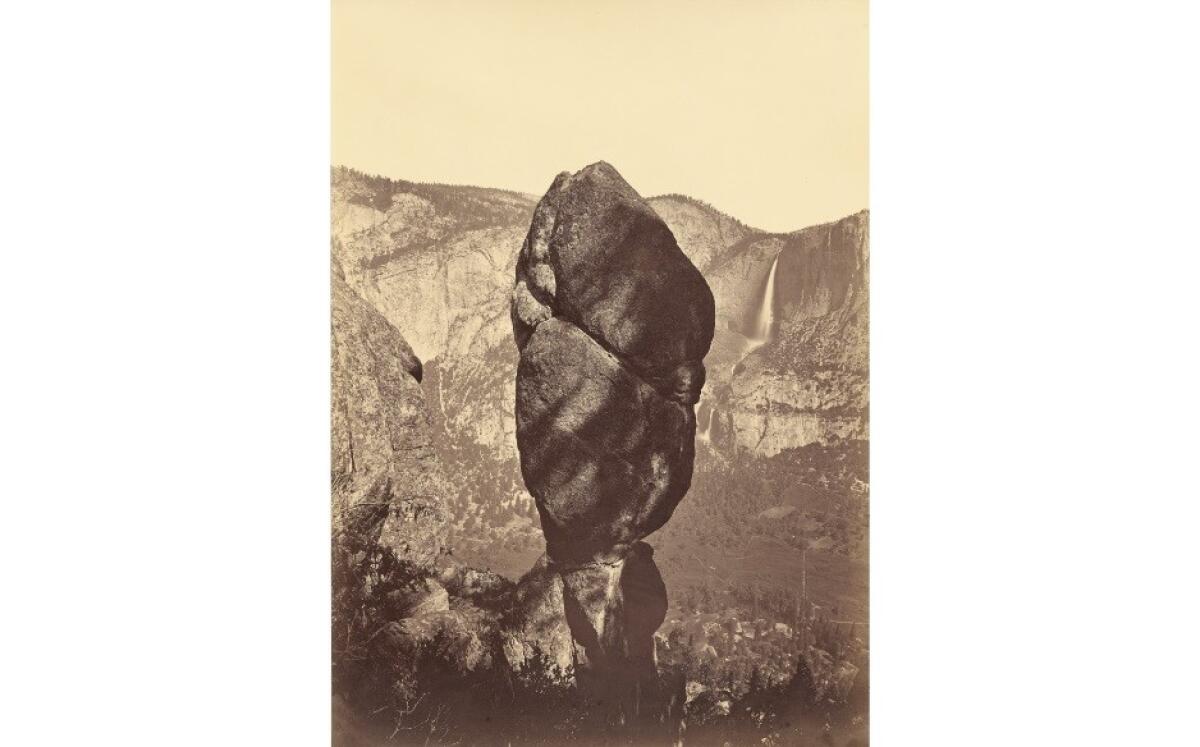

Watkins’ photographs were an appeal to painting’s stature not merely through subject but also through size and presentation. He made mammoth plate photographs of Yosemite, some as large as 2 feet on a side. He exhibited them elaborately framed and under glass — common today but an innovation for early camera work. He was insisting on an artistic equivalence between paintings and photographs.

He was doing something else too. The photographs are a glorious expression of what Green calls “cultural Unionism.”

The book charts the grave tug of war between pro-slavery and abolitionist sentiments, forces of secession and union, in California — a state barely more than a decade old when civil war erupted. Watkins, steeped in the debate, made breathtaking Yosemite photographs that draw a dynamic, informed visual connection with the Hudson River School, linking the untrammeled, politically ambivalent West with the leading artistic vision firmly established in the Union-committed Northeast.

The pictures had their acclaimed New York gallery debut in October 1862 at Goupil’s, a prestigious shop just a few doors down Broadway from Mathew Brady’s gallery. There, shocking photographs by Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan of the epic recent slaughter in Maryland at the Battle of Antietam were simultaneously hanging. In the stark contrast between bounteous life and ghastly death, eyes were glued to Watkins’ pictures of an ancient, spectacular American landscape few citizens had ever seen. Soon, they would move Lincoln and his cohorts, deep into a blood-soaked struggle, to initiate an unprecedented project creating the country’s first nature preserve.

Preserving the incomparable American landscape was conjoined with preserving the unprecedented Union.

Ironically, the absence of most of Watkins’ textual documents may have helped Green to come to this startling and invaluable conclusion, an insight much larger and more consequential than simply acknowledging the artist’s vital role in what would become the National Park Service. Without those primary sources, the chronicler of Watkins’ life turned by necessity to his life’s rich context. There was no other choice.

An unlikely connection

Watkins engaged a sizable network of major players, especially in Northern California. Among them were railroad baron and art collector Collis P. Huntington, a childhood pal with whom Watkins had moved west from their birthplace in rural Oneonta, N.Y.; writers Thomas Starr King, a Unitarian minister and orator, and Jessie Benton Frémont, social justice activist and daughter and wife of two influential senators; powerful San Francisco banker William C. Ralston; naturalist John Muir and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted; and California’s best landscape painter of the period, William Keith. Although careful not to attribute encounters that cannot be verified, Green constructs Watkins as a kind of Venn diagram of recorded interactions with figures from social, political, technological and cultural circles.

The picture is unexpectedly enhanced by a chance encounter that borders on the incredible. Green, who grew up in the Bay Area, mentioned to his father during casual conversation that his research had led him to a hitherto unknown figure — William H. Lawrence, chief executive of San Mateo’s Spring Valley Water Works, which had a monopoly on providing water to the burgeoning city of San Francisco. Lawrence, it seems, had bailed out Watkins from near bankruptcy by investing in his photography business after a shady 1875 deal almost ruined him.

Green needed to find out more.

“Well,” his helpful dad replied, “William H. Lawrence is your great-great-grandfather.”

Green reports that it took a few days for the shock of the serendipitous news to wear off before he remembered that Lawrence was his own middle name. The episode makes for an unpredictably personal interlude, one in keeping with the narrative’s conversational tone but all the more vivid given Watkins’ standing as a spectral apparition in the book.

The bibliography of sources, published and not, stretches to 25 pages. For good reason, though, we learn almost nothing directly about Watkins as a flesh-and-blood personality. His training in camera work is unknown. His late marriage to a young woman — an employee nearly 30 years his junior — approaches a blank slate. His temperament, personal foibles, scruples and integrity can be inferred only by working backward from his immediate milieu. Green does well with most of it.

Perhaps that’s because he understood that, despite the dearth of other paperwork, he did have access to the extraordinary pieces of paper on which Watkins’ hundreds of images are inscribed. He sold many photographs during his lifetime, especially in large albums, which survive today. These photographs, the reason for the story to be told at all, tell a lot of it. They are an incomparable primary source, telling us what — and how — Watkins saw.

Green traveled to the main repositories of Watkins’ art, from Los Angeles, Bakersfield and the Bay Area to New England, as well as to many sites recorded in the pictures. (Coincidentally, I lived in Oneonta for more than four years; the evocative descriptions are spot-on.) An avid hiker, he went to many precarious places. Incomparable information comes from knowing where the photographer stood to set up his bulky camera, how conditions change the view as light shifts during the day and, if possible, in what sequence a set of images was likely made.

Passages that analyze Watkins’ extraordinary compositions are among the book’s most revealing. We learn, for example, how the artist constructed scenes by hiding distractions behind boulders or circumnavigating a volcano to discover how best to convey its massive bulk. He was not, apparently, unwilling to cut down a tree if it got in the way of making the best picture of a place.

In addition to his two main trips to Yosemite, he photographed up and down the West Coast — at gritty but fabulously rich mines for gold, silver and copper; along the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River; around Mt. Shasta; at Spanish colonial missions, including in Tucson, Ariz.; in vast, newly irrigated farmlands in the naturally arid Central Valley; and more. Many were commissioned by businessmen eager to have great pictures to use in investor pitches.

An unfolding future

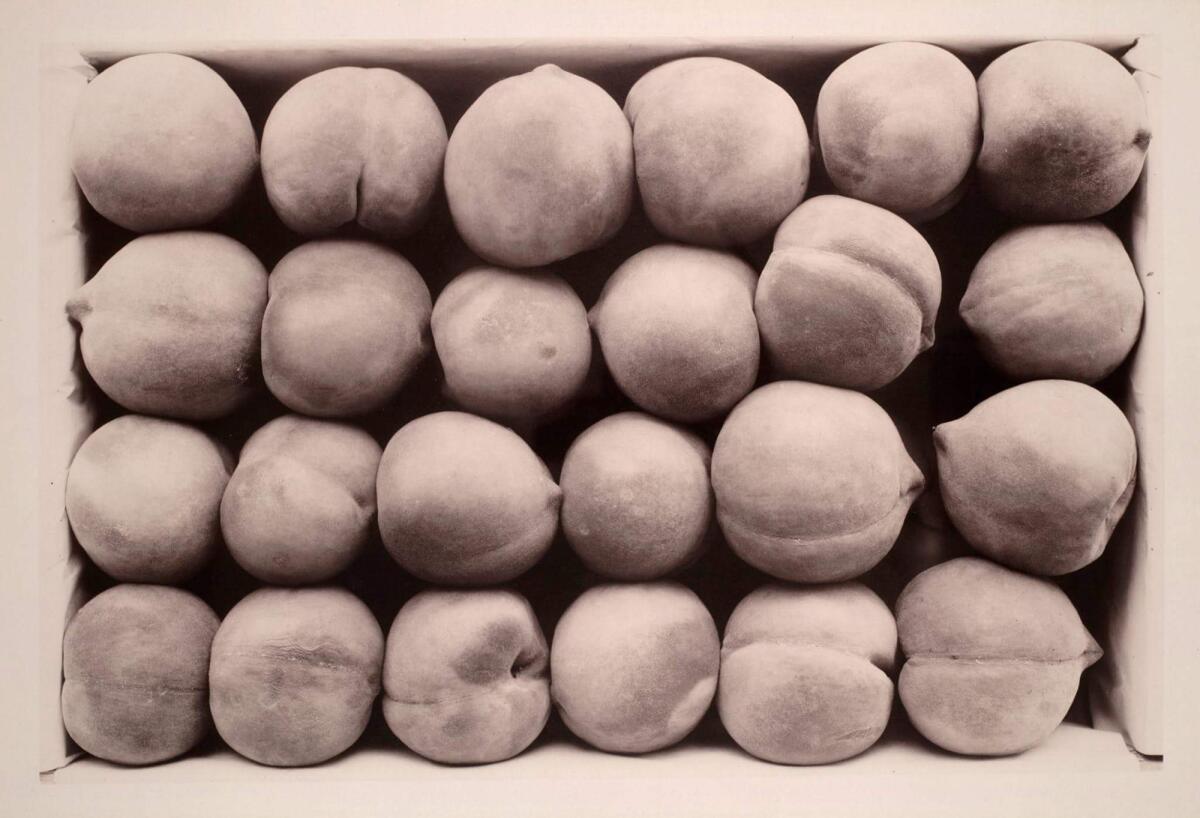

Exemplary is Watkins’ final masterpiece. An investor relations impulse may have informed “Late George Cling Peaches,” a circa 1888-89 Kern County image of two dozen fruit packed in neat rows in a wooden shipping box. Shot from above, with the boundary of the box coincident with the photograph’s frame, the crisply gridded picture today looks startlingly modern.

That’s because the landscape had changed. Watkins didn’t photograph a verdant tree laden with ripe fruit, which one might expect from Yosemite’s sublime visual poet. Instead, as this unconventional biography deftly explains, he pictured the measured, orderly result of epic human intervention in the chaotic landscape, which had transformed a desert into a cornucopia.

At the very moment Bierstadt was painting the last of the buffalo in a romantically mythologized Western landscape and Vincent van Gogh was abandoning Paris for ecstatic visions of the wheat fields of Provence, France, Watkins replaced a traditional garden of Eden with a new garden of industry. A brilliant artist with a camera was signaling the West’s unfolding future.

“Carleton Watkins: Making the West American,” Tyler Green, UC Press; 592 pp; 77 illus.; October 2018; ISBN: 9780520287983

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.