Philip Glass’ opus ‘Satyagraha’ brings collective communion — and otherworldly puppets — to L.A. Opera

- Share via

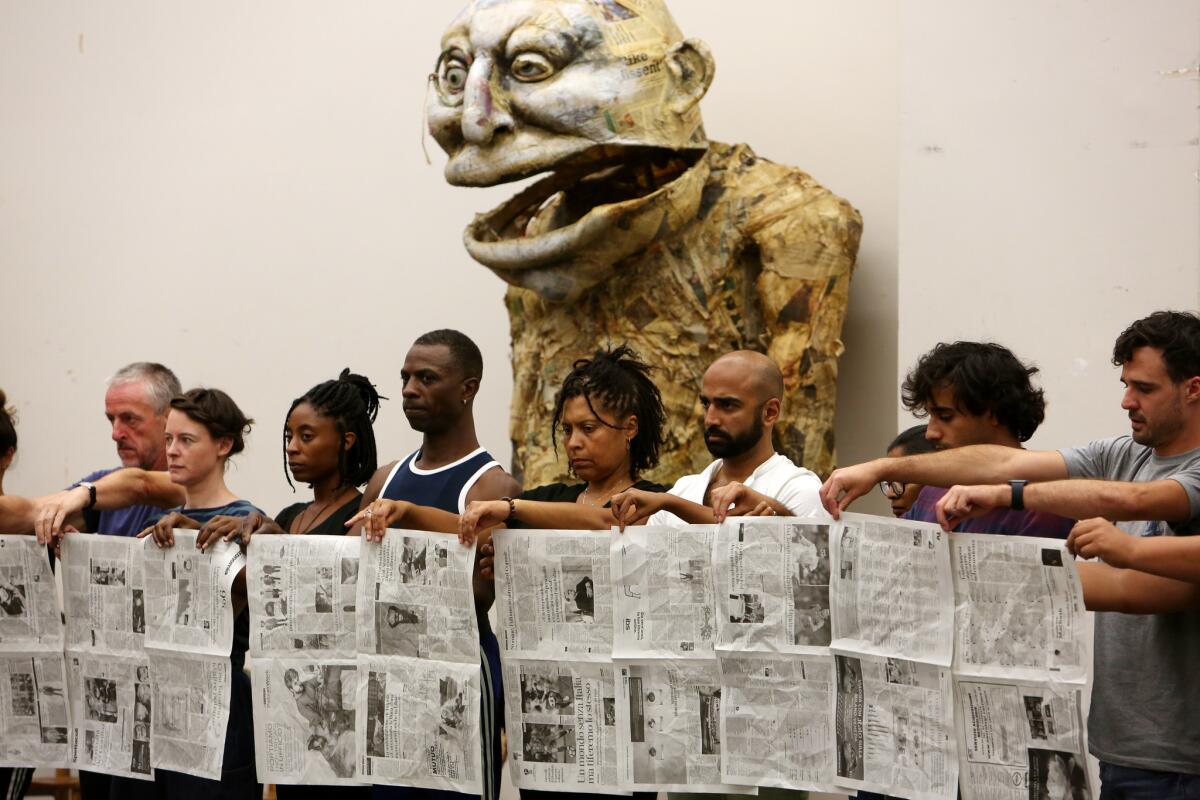

It happens so quickly that you are left wondering if it ever happened at all. During a frenzied onslaught of music dominated by a manic piano line, 11 massive puppets seemingly float onstage above the action in the Philip Glass opera, “Satyagraha,” a revival of which is running at Los Angeles Opera from Oct. 20 to Nov. 11.

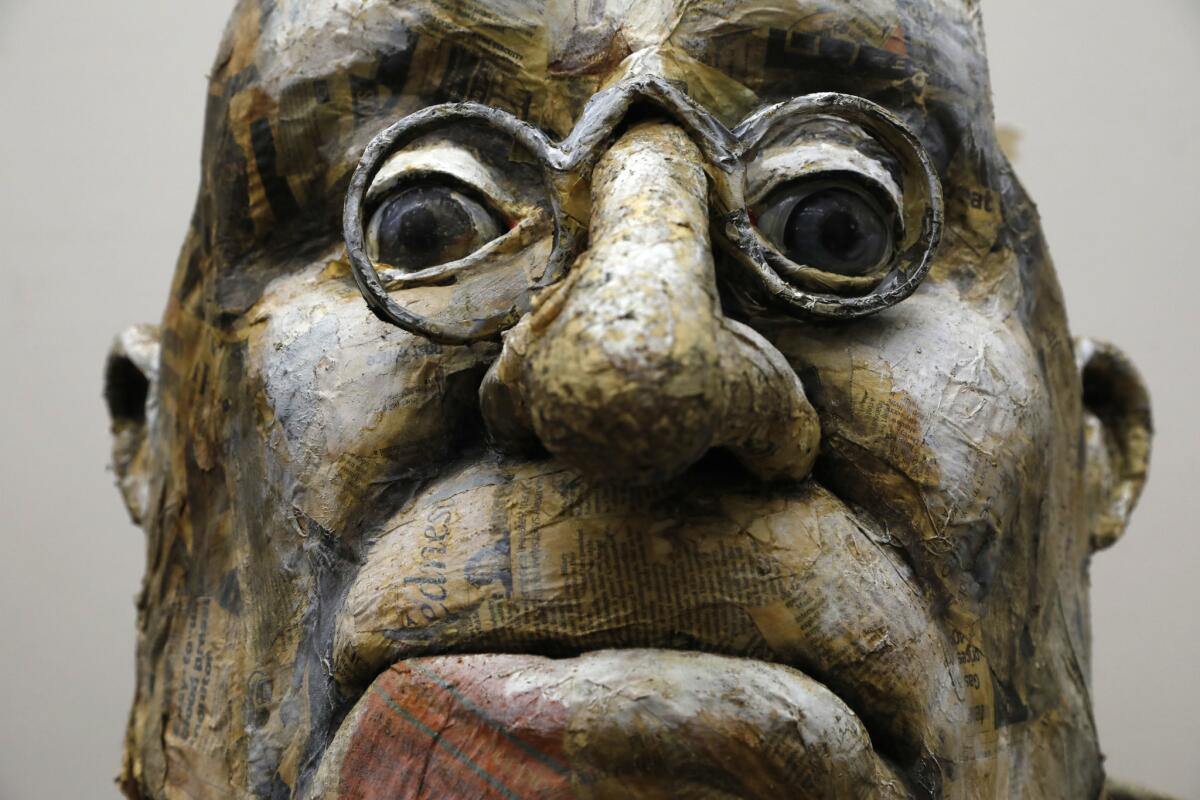

Made of yellowing newsprint and old wicker baskets, the towering apparitions grimace and grin, smirk and scowl, revealing razor-like rows of rotten teeth. They have bulbous noses, top hats and monocles. Their eyes squint and glare. They are the bankers, politicians and wall street brokers that nightmares are made of and they are propelled, half-ragged and aghast, into the spotlight by performers — some on stilts that resemble decaying wooden crutches.

During a recent weekday rehearsal, the grotesque puppets remain just long enough to take your breath away, and then disappear back into the shadows.

Strength doesn’t come through ego or force. It comes through a shared intention of what’s happening between people.

— Director Phelim McDermott

This trick is part of a mesmerizing production design by associate director Julian Crouch that acts as a living, breathing backdrop for an abstract, non-linear opera informed by a deep dedication to ensemble work as opposed to the glorification of any one star or individual.

“Strength doesn’t come through ego or force,” says director Phelim McDermott. “It comes through a shared intention of what’s happening between people — of what people can do collectively.”

In another display of stunning teamwork, members of the chorus sing the word “ha” 1,992 times during one section of the opera. The word, intoned repetitively in a kind of hypnotic chant — “ha ha ha ha ha ha ha” — is not supposed to symbolize laughter, but rather to stimulate the dream-like environment that allows the opera to morph into a meditation about the power of collective action to effect change on both micro and macro levels.

It’s a mantra, an om, of sorts. The spiritual sound that, in the Hindu tradition, signifies a higher level of consciousness.

That sound is embodied in the person of Mohandas K. Gandhi (played by Sri Lankan tenor Sean Panikkar) during the 20 pivotal years he spent in South Africa developing his philosophy of nonviolent resistance to political oppression.

“Satyagraha” is an L.A. Opera company premiere and — in addition to “Einstein on the Beach” (2013) and “Akhnaten” (2016) — completes the company’s staging of Glass’ “portrait trilogy” of operas about powerful thinkers who changed the world. This version is a revival of a 2007 staging in the United Kingdom presented by the English National Opera and Improbable Theatre, co-produced by New York’s Metropolitan Opera, and directed by McDermott.

McDermott co-founded Improbable in 1996 with Crouch and others, and the idea of a cohesive, non-hierarchical ensemble is dear to his heart. It is also, he says, an extension of the word “Satyagraha,” which translates from Sanskrit as “truth force,” and was coined by Gandhi to describe the ideology he used as a leading force in the Indian independence movement.

The opera is more of a fever dream than a biopic, and hovers around a profound moment in Gandhi’s life when he was kicked out of a first-class carriage in South Africa for the color of his skin. He had to decide whether to go home, or stay and resist. The world knows his answer, and the opera seeks to crack open the spirit of that choice in order to convey it in an atmosphere thick with provocative sights and sounds.

“I can’t help but feel that presenting a piece like ‘Satyagraha’ is really what we’re here for,” says L.A. opera resident conductor, Grant Gershon,. “It’s a piece by a living American composer who has a lot to say and who says it really beautifully. It’s a piece that can speak to many different kinds of audiences, and it has such a strength of purpose to it.”

Since there is no driving narrative in any traditional sense, the task of conveying what it all means falls to the opera’s nine soloists, 40 chorus members, four supernumeraries, 12 “skills ensemble” members and 46 orchestra musicians, who taken as a whole, weave the tapestry that becomes the experience of the show.

The skills ensemble are the silent performers who propel the puppets and constantly shift and change the landscape onstage by manipulating basic materials including paper, sticky tape, wicker and corrugated tin — building transitory images as they go. Paper that waves and rages like fire, a fish that turns into Ganesh, a procession of newspaper that whizzes across the stage like a conveyor belt. (18,900 sheets of newspaper, all told, are used in this production.)

There is no dialogue, just pieces of music of varied length with lyrics derived by Constance DeJong from the sacred Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita.

“I’ve never sung something with so much repetition, and musically it can be challenging because you have to have extreme focus, otherwise you’ll get lost,” says J’Nai Bridges, a mezzo-soprano who plays Gandhi’s wife Kasturbai. “But at the same time, you also have to let go. It’s a strange balance.”

Peter Relton, associate director of the production, says it doesn’t matter that most audience members won’t understand the words. Glass’ intention, he says, was to create a distinct “sound world.”

“While the soloists are singing, and moving through this world, the skills ensemble creates the atmosphere and the environment they’re in,” he explains.

Rob Thirtle, skills ensemble lead, is one of a few members of the performance team to have been with the production since 2007. He jokes that he is “multi-talentless” and that he ended up in the skills ensemble because he is “not very good in a lot of areas.” But really, he is a skilled craftsman and an adept performer who knows how to move with purpose in silence, and understands the transformational power of improvisation onstage.

The idea of metamorphosis is specific to the design concept, Thirtle says, adding that Crouch says he considers puppetry to be a “gutter art”— a puddle in the road that isn’t particularly pleasing to the eye, but is transformed into something beautiful as soon as the moon is reflected in it.

“In this show, our hope was to transform found garbage — bits of materials blowing around on the street — and to turn those into beautiful images before the audience’s eyes,” he says. “Images that appear for a moment and then disappear back into the wind.”

In order to allow this kind of controlled, creative chaos to thrive onstage around her, Bridges says that she has learned to relinquish her ego entirely. A rare practice, indeed, in the world of opera.

“It really feels like we’re just one big unit,” she says. “Not one person is more important than the other.”

That once again, says McDermott, is the definition of Satyagraha. It’s a message he feels is more pressing than ever, and one he hopes the audience carries with them into the streets after the show.

‘Satyagraha’

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles

When: 7:30 p.m. Oct. 20, 27, Nov. 1 and 8; 2 p.m. Nov. 4 and 11.

Tickets: Starting at $19

Info: (213) 972-8001, www.laopera.org

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.