For Heidi Duckler, it’s location, location, location

- Share via

It’s probably accurate to assume that most civilized visitors to Los Angeles City Hall’s third-floor rotunda do not try to climb the marble columns, balance on the historic light fixtures or lie on the ground directly under the enormous bronze chandelier for perspective’s sake. But on a recent Saturday, Heidi Duckler and two of her dancers did exactly that, laying claim to the notion that if you can’t fight City Hall, you might as well dance in it.

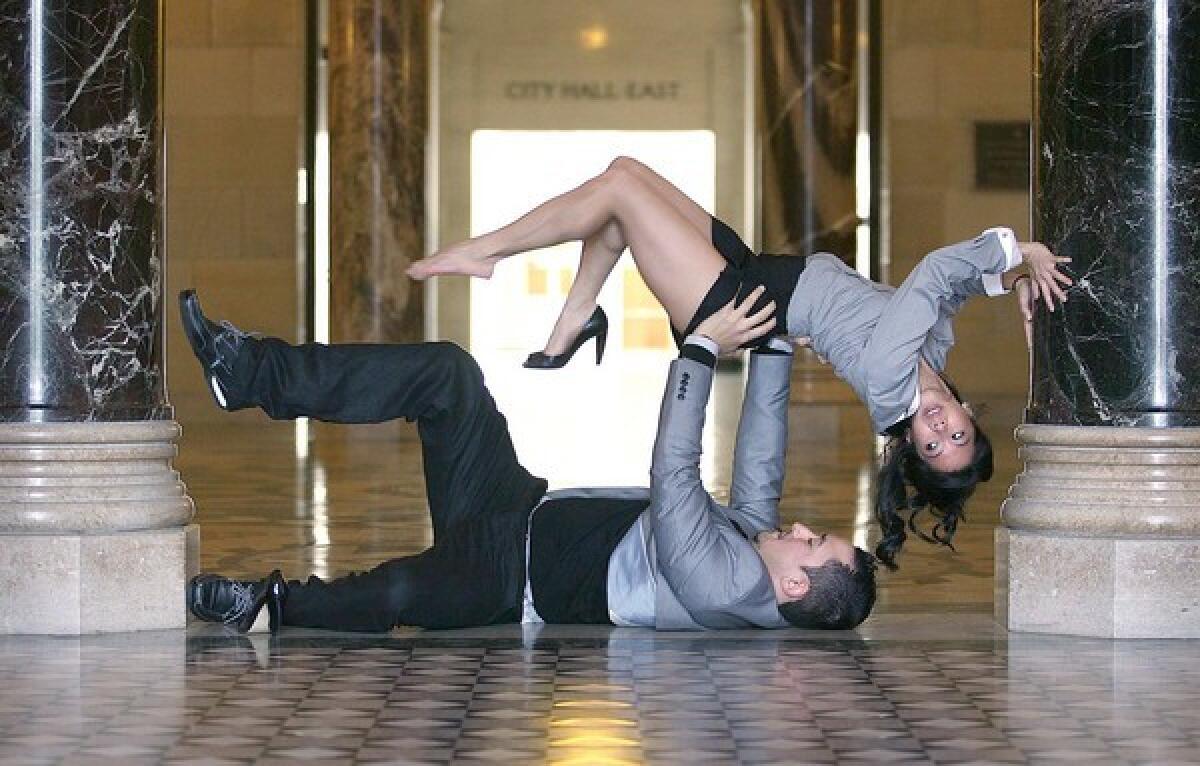

During a first rehearsal for a new site-specific production by Duckler’s Collage Dance Theatre, Marissa Labog and Roberto Lambaren experimented with rigorous horizontal and inverted balance poses between walls and columns that reflected formidable break-dancing skills while Duckler pointed out various Roman and Byzantine architectural details of the cavernous rotunda to a reporter. They, she said, “were begging to be animated. This is the perfect place to celebrate.”

Indeed, the 57-year-old choreographer has good reason to feel festive. Her company, which has produced more than 60 site-specific works in a dizzying array of locations, turns 25 this year, and the normally prolific Duckler has never been busier. She’s booked a slew of gigs that commemorate her past, point to her future and culminate with “Governing Bodies,” a work that will incorporate break dancers, hula dancers, live musicians and ideas about public space and democracy that will premiere at City Hall in November.

Before that there’s a performance installation in a Culver City art gallery (Saturday), a production in a vacant lot in Cambodia Town in Long Beach, a reprise of her first work, “Laundromatinee,” and participation in a summer arts festival in Yaroslavl, Russia.

A nationally recognized pioneer of site-specific dance, Duckler was also one of 16 choreographers featured in a recently published anthology by the University Press of Florida called “Site Dance,” which also profiled site-specific luminaries such as Meredith Monk, Joanna Haigood and the Los Angeles-based Stephan Koplowitz. Yet “I still feel like I’m just a kid in the sandbox,” Duckler said during the City Hall rehearsal as she watched Labog and Lambaren perform precarious, tango-like maneuvers on a ledge that jutted out above a flight of stairs leading to the second floor. “With my work, each project is always so unpredictable . . . it’s built in anti-burnout.”

Although it’s a milestone for any dance company to thrive for 25 years, Duckler’s robust longevity especially stands out in Los Angeles, a city with limited funding and producing venues for dance artists. “This is a tough town for dance companies, and to survive in L.A., a choreographer has to be especially tenacious,” says Michael Alexander, the artistic director of Grand Performances, which has a long-standing commitment to producing dance in its annual outdoor summer series at California Plaza.

Alexander had commissioned Duckler in 1998 to create a dance in the plaza’s fountain called “Liquid Assets,” and he remains an avid supporter of her work. “She attracts people who are often not your typical modern-dance audience, and she gets them to go places they’d otherwise never visit. Then she helps them interpret those spaces in fresh and interesting ways,” he observes.

Over iced tea at a Culver City cafe a few days after the City Hall rehearsal, Duckler, a petite blond woman with a good sense of humor, has no trouble pinpointing the secret to her success. “The world likes to say no, but I nudge it to say yes,” she says, chuckling yet perfectly serious.

Beginning in 1988 with her first site-specific work, “Laundromatinee,” which had dancers diving into washing machines at a Santa Monica laundromat, Duckler adopted a trial-by-fire approach to dance-making as she encountered one uniquely site-specific obstacle after the next. She had a terrible time, for example, persuading police officers to perform with her dancers in her 2006 “C’opera,” which took place at the Los Angeles Police Academy in Elysian Park. There was the screaming match that same year with owners of a Chinese laundromat in New York who didn’t understand that Duckler needed multiple rehearsals to re-create “Laundromatinee.” And there was the time she almost had her permit revoked by Los Angeles County to perform her 1995 “Mother Ditch” in the Los Angeles River.

Factor in the rats in the Los Angeles Subway Terminal building when she staged her 2000 “subVersions,” numerous headaches with obtaining other permits and permissions, and the general unpredictability of architectural surfaces, and it’s easy to believe Duckler when she says she’s not the kind of choreographer “who’s a control freak. In fact, my sister says I thrive on chaos.”

“You could put Heidi in any environment, and she’d make it work for her,” observes her sister Merridawn Duckler, a writer who has created numerous texts for Duckler’s projects. “She was always very site-specific, so it’s not surprising she wound up doing what she does.”

Duckler grew up in Portland, Ore., in an artistic family that had a stage and a ballet barre in its basement. “Everyone in our family had a vivid imagination, but it was Heidi who was very physical,” her sister recalls. “She gave dance lessons to kids in the neighborhood and charged them a nickel.”

Devoted to ballet as a child, Duckler studied dance at Reed College and the University of Oregon and ran her own studio in Portland before decamping to Los Angeles and deciding to get her master’s degree in dance at UCLA. Influenced by pop culture and visual artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and determined not to create the kind of insular dance that she felt appealed only to other dance makers, she had a big “aha” moment during the creation of her thesis project.

“I had filled the stage with so much stuff and I thought, ‘Why am I bringing environments to the proscenium stage? Why not explore environments the way they are?’ Basically, I didn’t want to limit myself to what fit in my Volvo,” she says.

Initially Duckler found herself drawn to “populist sites,” such as laundromats, gas stations and libraries, and later gravitated toward buildings and places rich in architectural and local history. Over the years, she experimented with including audiences in her work and redefining their relationship to a performance. She also developed her own choreographic process, which departs from the traditional model of spending hours developing dance vocabulary and phrases in a studio and then teaching it to dancers. Rather, she has always chosen performers with strong improvisation skills, eclectic movement training and an ability to autonomously respond to environments.

“It’s a very intuitive, collaborative process,” she says, also noting the crucial role her sister plays in the initial conception of her works. “We’ll talk concepts, character and casting and how you might physicalize those concepts,” she says.

Duckler feels she embarked on a new chapter of her career in 2007, when she created a work inside a glass enclosed bridge in Hong Kong. Since then, she has been hungering for more commissions abroad and sees her upcoming trip to Russia as a hopeful harbinger. “It’s a whole new challenge, going to a different culture and making work that resonates,” she says.

With plans to increase the number of projects she annually takes on, Duckler definitely plans to stick around for another 25 years. “I love that my works make connections between all kinds of places and all kinds of people,” she says. “Site work is such a rich and fertile field.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.